Families still seek answers in Santa Fe

Texas records laws keep loved ones in dark after shooting

By Shelby Webb and Nick Powell STAFF WRITERS

Steve Perkins knows his wife is dead.

He knows Ann was trying to get students to file out of Santa Fe High School on May 18 after a fire alarm blared across campus. He knows she was shot at least once. Witnesses told Perkins his wife fell just outside an exterior door near the school’s art classrooms.

It is the information Perkins does not know that has gnawed at him since.

“I don’t know how many times she was shot,” Perkins said. “I’ve got one medical certificate that showed multiple gunshot wounds, but that was amended and said a single gunshot wound. I can’t see the medical examiner’s report; I can’t view the video of the shooting — I’ve been told I can’t have anything.”

Families of at least six children and staff members who died in Texas’ deadliest K-12 school shooting, as well as two injured survivors, still are searching for answers 10 months after a teenage gunman blasted his way through the Galveston County school. Each time they have requested records — including medical examiner and autopsy reports — they have been denied.

The absence of information about the Santa Fe shooting stands in stark contrast to the trove of details released to families and the public in the immediate aftermath of a mass shooting three months earlier at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., that left 17 dead and 17 injured.

The disparate responses to the Parkland and Santa Fe shootings, however, go far beyond the information divide.

In the Parkland case, Gov. Ron DeSantis suspended Broward County Sheriff Scott Israel for failing in his duties and has considered action against Broward County School District Superintendent Robert Runcie. Two campus monitors at Stoneman Douglas High School were fired and four other employees reassigned for their lackluster responses. After law enforcements’ response was scrutinized, two Broward County sheriff ’s deputies resigned, one was suspended and a fourth was put on “restrictive duty” and forced to surrender his badge and gun.

Law enforcement released a timeline of the shooting the day after 19-year-old Nikolas Cruz allegedly rained bullets on unsuspecting students and staff. In less than 10 days after the shooting, authorities released records showing that concerned neighbors and others had called the Broward County Sheriff’s Office 18 times in nine years to warn about the eventual Stoneman Douglas shooter, with one telling officials he worried the Florida teen “planned to shoot up the school.” A variety of released records explain why it took more than 11 minutes for officers to enter the classroom building where Cruz committed the massacre.

An appointed group of educators, parents and law enforcement officials compiled a 439-page report detailing systemic failures before, during and after the Parkland shooting, and created alist of specific recommendations stemming from those missteps.

Information vacuum

However, in the 10 months since the Santa Fe High School shooting, law enforcement has not released a detailed timeline of the shooting. There is no official account of the shooter’s movements, or whether there was a prolonged exchange of gunfire with police who responded to the scene. There is no indication of a motive or whether school district authorities or local law enforcement had any previous indication that the accused gunman, Dimitrios Pagourtzis, a then-17 year-old senior, could be a risk to himself or others.

No independent commission has investigated what happened at Santa Fe High School, and none has been proposed by state lawmakers. No law enforcement officials have explained why it took 30 minutes to arrest Pagourtzis. No one knows if Santa Fe Independent School District employees or local law enforcement officers in Texas made missteps that may have contributed to the shooting that killed 10 and wounded 13 people.

The glaring differences in information and accountability for two similar mass shootings boil down to one factor: public records laws.

Florida’s public information statutes are considered among the most robust in the country and give the general public access to information, sometimes within hours of a crime. In Texas, a widely used exception to the state’s public information law gives prosecutors broad discretion to withhold information about felonies from the public, news media, victims of crimes, even defendants, until trial.

For families of those killed or injured at Santa Fe High School who spoke with the Houston Chronicle, the information blockade likely means they will not know how their loved ones were killed or wounded for months, maybe years to come. Without legislative changes to the public information law, they will learn of grisly details surrounded by strangers in a courtroom when evidence is presented during the alleged gunman’s trial, which is not expected to begin until at least the end of 2019.

The unanswered questions about what happened in Santa Fe has made it difficult for victims’ families to move on.

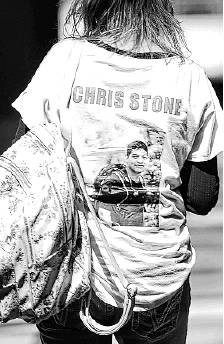

“I have no answers,” said Rosie Y. Stone, whose 17-year-old son, Chris, was killed. “That’s just a closure we need. They’re making us sit here and wait and wait and wait and live with the not knowing. And that’s what makes life so much harder.”

When FBI agents pulled Lori Alhadeff and her family into a room during the early hours of Feb. 15, they did not just tell the distressed mother that her 14-year-old daughter Alyssa had died in the mass shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School. They said she had been shot in the face.

Horrified and wanting more answers, Alhadeff drove 45 minutes to the Broward County Medical Examiner’s Office later that morning and demanded to see her daughter’s body. Employees refused, but gave her an 8-by-10-inch color photograph of Alyssa’s face. It looked unscathed, and Alhadeff soon learned that while her soccer-loving daughter suffered gunshot wounds to the top of her head and nine other places, no bullets damaged her face.

“I mean, it’s painful regardless of however you say it or look at it or talk about it,” Alhadeff said. “But it did provide some type of just closure and knowing that this is what happened.”

The families of homicide victims in Texas, however, rarely get such closure in the days, weeks and months after their loved ones die.

The Texas Public Information Act gives prosecutors sweeping authority to keep documents secret — including medical examiners’ reports, police radio communications, incident reports and almost everything else — thanks to a law enforcement exception written into the law.

If the district attorney’s office or law enforcement agency claims that releasing information will “unduly interfere” with prosecution or investigation, it can shield those documents from anyone outside the criminal justice system. In those cases, families and the public can gain access to the information only after a person is convicted and sentenced, though it still can be withheld if a conviction is appealed.

Galveston County District Attorney Jack Roady, who has asked local government agencies to shut down public information requests relating to the Santa Fe High shooting, said he could not release documents or information to victims’ families or survivors without also releasing them to the general public and news media.

Allowing the information to get out into the public could result in trial by media and potentially impact witness testimony, he said, making it more likely that Pagourtzis would not receive a fair trial. That could result in delayed justice for the families.

“The more of that information that gets out there to the public, the more likely it becomes that jurors will start forming their own opinion about what had happened and the more difficult it would be to find jurors who would be willing to set aside those opinions and evaluate the case based on the evidence presented at trial,” Roady said.

Defense attorneys for Pagourtzis already successfully argued that pre-trial publicity would make it unlikely that their client would have access to a fair trial in Galveston County — a state district judge last month ordered the trial be moved.

Joseph Larsen, a Texas lawyer who specializes in media and public records law, said Roady has the ability to release whatever he wants.

He cited mugshots as an example. Sometimes prosecutors argue to keep those private under the law enforcement exception, but police regularly release mugshots and ask for the public’s help locating suspects.

“The law enforcement exception is a discretionary exception,” Larsen said. “They don’t have to claim it.”

The exception may be elective, but it has become a de facto rule in much of the Lone Star State. Andy Kahan, director of victims services for Crime Stoppers of Houston, said in his 27 years of working with the relatives of homicide victims, he never had acase in which families were given access to an offense report before trial. When some of the families he guides grow frustrated by the information vacuum, he said he tries to explain what is at stake.

“Like it or not, you get one bite at this apple, and you do not want to do anything to cause harm to this case, that may cause a reversal or a mistrial,” Kahan said. “Your goal right now is to get justice. That’s primary.”

While concerns over defendants’ rights tend to overshadow victims’ and the public’s right to information in Texas, almost the opposite is true in Florida.

Most aspects of what can and cannot be released are enshrined in the state’s public records laws, leaving no discretion to state attorneys or Florida’s attorney general.

Incident reports — which include the address of the crime, the arrested person’s name, his date of birth, home address and general details about the alleged crime — sometimes are available within hours of a crime. Almost every document given to adefendant becomes public record. Once a criminal investigation is complete, most of the information compiled by law enforcement becomes public.

Three weeks after the Parkland shooting, the Broward County Sheriff’s Office released audio recordings and a detailed timeline of its response, which exposed systemic failures. For months, each week seemed to bring a new revelation about the case, Cruz’s troubled past, law enforcement’s bungled response, and shortcomings in school actions and policies.

Barbara Petersen, a Tallahassee, Fla.-based lawyer who heads the nonprofit First Amendment Foundation, said the release of information in the Stoneman Douglas case showed how law enforcement and others could better respond to tragedies.

“We cannot depend on government to police themselves or self report,” she said. “We have been able to point out flaws in policies and procedures, and that has resulted in those policies and procedures being reevaluated and, in some cases, changed.”

A detailed timeline

Nineteen days after the Parkland shooting, Florida state Sen. Bill Galvano presented the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Public Safety Act to the Florida Senate.

One of the law’s highlights, the Republican lawmaker said, was the creation of a 20-person commission tasked with creating a second-by-second timeline of the shooting; reviewing interactions between the gunman and government entities; analyzing law enforcement’s response during the shooting; and studying whether policies and procedures were followed before and whether those guidelines needed to be changed. The commission also was asked to recommend better ways local law enforcement agencies could coordinate in emergency situations.

The result was a 439-page report that laid bare excruciating details of Cruz’s life, school district missteps, law enforcement failures and problems that compounded themselves in the shooting’s aftermath.

For example, the doors lining the hallways of classroom building 12 could be locked from the outside only, forcing teachers to open and lock the doors from the outside to keep the gunman from coming in; many classrooms’ “hard corners,” where students and staff are instructed to hide during potential incidents, were crammed with furniture; few in the school had attended an active-shooter training.

When law enforcement officers and emergency workers did arrive on scene, they struggled to determine which classrooms had been searched, establish a command post and took crucial minutes to put on their bullet-resistant vests; responding departments were unable to communicate and coordinate with each other because they had different radio systems; a lag in surveillance video led law enforcement to believe the shooter still was on campus when he had escaped minutes earlier.

Those shortcomings inspired dozens of recommendations in the initial report: Schools should provide live and real-time security footage to local law enforcement agencies; every school resource officer should be equipped with a bullet-proof vest and rifle; law enforcement agencies should require communications interoperability with all other agencies in their county; lawmakers should change statutes to require mental health providers to release information about potential threats patients may pose to others or themselves.

Pinellas County Sheriff Bob Gualtieri, who chaired the commission, said those recommendations and findings will help first responders lessen casualties when — not if — the next mass shooting occurs in Florida.

“You don’t know what you don’t know until you look at it,” Gualtieri said. “We’ve been able to look at what happened there and learn from it. That’s the objective. You always want to learn from other situations, learn from the past to try to make yourself better and stronger for the future.”

In Texas, no official commission was convened to investigate what happened during the Santa Fe shooting.

Gov. Greg Abbott convened three days of roundtable discussions at the state Capitol on school safety that included testimony from Santa Fe shooting survivors, as well as students, parents, teachers, lawmakers, law enforcement officials, and interest groups.

Shortly afterward, the governor laid out a series of school safety proposals, from increasing law enforcement presence in schools to boosting emergency response training.

State Sen. Larry Taylor, who represents Santa Fe and chaired the newly created Senate Select Committee on Violence in Schools and School Security, said a bill still was being drafted that would address some of the issues discussed during the committee, but stopped short of saying he favored a Parkland-style commission investigating the shooting itself.

“I really don’t see what we’re going to get extra out of the particular Santa Fe case,” Taylor said. “The real issue for me is trying to identify these people before they do harm and do everything we can to actually prevent it.”

Not all Parkland families are convinced of the Florida commission’s value.

Manuel Oliver, whose son, Joaquin, was killed during the Stoneman Douglas shooting, pointed out that only a handful of victims’ parents were included as members of the commission.

Oliver became wary that its members were being influenced by gun rights lobbyists after the commission recommended arming school teachers in its final report. He said his suspicions were confirmed when Gualtieri, the commission chairman, appeared on NRATV, the internet webcast network of the National Rifle Association to discuss the commission’s findings.

“These commissions are, in some way, formed by members that have one thought about these situations,” Oliver said. “So, I don’t trust commissions that much.”

Families of Santa Fe victims and survivors do not necessarily share Oliver’s concern. If nothing else, they say, a formal commission would allow them to hold local law enforcement and school district officials accountable for any shortcomings in the response to the shooting.

Scot Rice, whose wife, Flo, a substitute teacher at Santa Fe High School, was shot through the legs and still is recovering, said that a commission would help the school district develop a more comprehensive safety plan to guard against a similar shooting in the future.

“We’re not doing a ‘whodunit,’” Rice said. “We want to know what the failures were that led up to this, and then what did the school do to fix the problem?”

Shaheera Jalil Albasit, whose cousin, Sabika Sheikh, was a Pakistani exchange student at Santa Fe High School killed during the shooting, has acted as the go-between for Sabika’s family in Pakistan. Jalil Albasit considers the Parkland commission “the benchmark,” and said she has resorted to scouring the internet for news stories about what happened to Sabika to fill in the gaps in the public account.

“We are just now putting the pieces together, finding accounts on our own, exploring through the internet, exploring through Facebook groups, reaching out to people on our own to put the pieces together, to understand where Sabika was,” Jalil Albasit said. “Was she the last person to go? How did it happen? How did he storm the room?”

Jalil Albasit, a graduate student living in Washington, D.C., said the Sheikh family’s geographic distance from the crime has exacerbated the lack of information on the shooting.

“It feels sometimes that we are up against the entire state machinery, which is so not cooperative,” Jalil Albasit said.

‘Not … Kennedy’

There is a broad spectrum of grieving for families of mass shooting victims. Some have used the Santa Fe and Parkland shootings as a call to action, fueling activism around gun control, mental illness and school safety. Others have withdrawn from the public eye, preferring to grapple with the loss of loved ones in private.

Those differences mirror the desire for more public information. For Steve Perkins, the sudden loss of his wife, Ann, has left him feeling like he is living a remote existence — “This is Mars,” he says — and the loneliness sparks more questions that only could be answered by the information withheld by law enforcement investigating the shooting.

“I would at least like to know, did she suffer?” Perkins said. “Because, if I could see that she fell and she just didn’t move, I know that she went immediately. And if she didn’t go immediately, I at least know that she was passed out.”

Others, like Recie Tis-dale, whose mother Cynthia , a substitute teacher killed during the Santa Fe shooting, are more circumspect about what additional information would accomplish.

A League City police detective, Tisdale understands better than most the tight-lipped nature of criminal investigations. Tisdale said that even as a law enforcement official, he has been denied access to certain information about the Santa Fe shooting. Despite working investigations for a living, he does not want to pry further into the circumstances of his mother’s death.

“I’m not one that really wants to know a lot of details,” he said. “I know my mother was killed and it’s very unfortunate, and I don’t need to know every last detail on how she was killed. I can figure that out in my own mind.”

Back in Parkland, Manuel Oliver says the availability of detail about mass shootings may not be the emotional salve that families of Santa Fe victims hope, even as he acknowledged he would be “screaming for those answers” about the Stone-man Douglas shooting if he did not have them.

Knowing every gruesome detail of how his son, Joaquin, died — including where he was and how many times he was shot — has not changed the fundamental facts.

“The only answer is, a shooter came into your school and murdered people. What else do you need to investigate?” Oliver said. “It’s not the murder of Kennedy. What else do you need to know?”

‘How he left’

Rosie Stone envisions a larger cause in her demand for answers. The Santa Fe shooting was the first mass school shooting in Texas in more than 50 years, and Stone sees it as the school district’s responsibility to share the necessary information to prevent it from happening again.

She wants to know why Chris Stone was in the art classroom closet when he was killed. Why was the classroom’s back door locked? How did the gunman enter the building?

The more the public knows about the shooting, she reasoned, the less likely another parent will be kept up at night obsessing over the same questions.

“I know how my son went into this world. I want to know how he left this world.” shelby.webb@chron.com nick.powell@chron.com

Sunshine Week This concludes our reports related to Sunshine Week, when advocates of open government celebrate the value of the First Amendment and assess the state of freedom of information.