SENIOR LIVING

TECH RIDES THE ‘GRAY TSUNAMI’

Age-tech aims to keep booming demographic thriving. Can it?

By Mandy Behbehani

“Where would you like to go?”

Anne Chen-Cook places virtual-reality headsets on Claris MacConnell and Al Neubieser. “For a Saharan camel-back ride or hot air ballooning in Portugal?”

“I’ll go ballooning,” says MacConnell, 93, sitting in her wheelchair in the common area of Sunny View, a resortlike senior-living facility in Cupertino.

Chen-Cook, a Sunny View lifeenrichment specialist, opens the program on her iPad and sends MacConnell and Neubieser to Portugal, where they hover in the sky.

“What can you see?” Chen-Cook asks.

“Farmland,” says MacConnell.

“Nothing!” jokes Neubieser, 86, who has vision only in one eye and is the resident comic at Sunny View.

Chen-Cook keeps manipulating the program by Rendever, a mobile virtual reality platform that provides curated content for older adults. “I can’t see depth,” Neubieser complains.

Chen-Cook transports the pair to a dinosaur museum in Australia and then suggests their old neighborhoods, navigating to a cross street near Neubieser’s old address in Forest Park, Ill.

“That’s my old street, Thomas, and that’s Adams,” he cries, naming the familiar streets. “I remember that white house on the corner.”

Welcome to technology’s new wave: age-tech — the preferred term for products and experiences aimed at America’s “gray tsunami.” According to the U.S. Census Bureau, there are an estimated 73 million Baby Boomers. And the Census’ 2017 National Population Projections showed that by 2034, seniors 65 years and older will outnumber children under 18.

The tech world is taking note, racing to serve this aging demographic — a group that, until now, has essentially been ignored by the industry. Whether it’s developing products that allow seniors to age in place or live in retirement homes, assisted-living facilities or memorycare centers, this is tech’s next frontier. Age-tech today promises to connect seniors with their families, increase their mental stimulation, deter isolation and keep them safe and healthy.

The products and services run the gamut: Bay Area startups GoGoGrandparent and Onward Rides connect seniors to rides they can book without using any technology themselves, while robotic pets are used to calm anxiety in dementia patients. There are goggles that allow those with macular degeneration to see, and toilets that analyze bowl contents for signs of urinary tract infections and dehydration. Tech startups are popping up all over, eager to provide solutions — and make huge profits. (A complete IrisVision goggles kit costs $2,950.)

“If I say, ‘Alexa, play music,’ she plays music. If I say, ‘Alexa, what time is it?’ she’ll tell me. If I say, ‘Alexa, turn off light,’ she’ll turn it off. She’s like a good friend.”

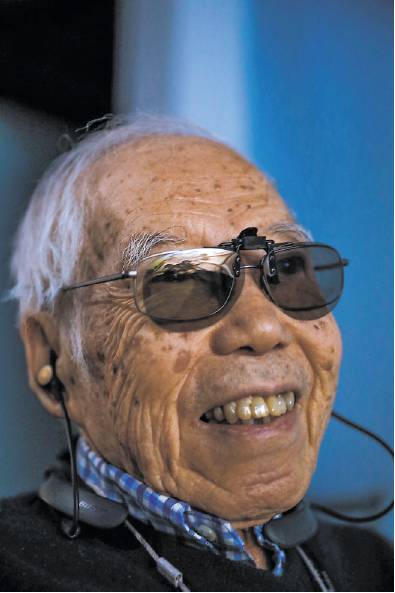

Al Neubieser, 86, shown below at left with Claris MacConnell, 93, wearing VR headsets

These products are not without their critics in the senior living industry, some of whom worry that instead of fostering engagement, tech might encourage isolation, with everyone on their own devices in their own rooms. They say tech systems require ongoing training of the elderly, who often don’t retain what they learn. As with any technology that tracks and monitors personal data, there are privacy concerns. And, some warn, bits and bytes are no substitutes for real-life connections.

“Tech should never replace human interface,” says Candiece Milford, managing director of marketing at the nonprofit Rhoda Goldman Plaza assisted living facility in San Francisco.

But others swear by age-tech, and seniors seem to be expecting it.

“With the increased penetration of smart devices into people’s homes, (people) are wanting to see these things in senior living communities,” says Davis Park, executive director of the Center for Innovation and Wellbeing at Front Porch, a Southern California nonprofit that owns Sunny View and nine other senior communities in California. “When they’re looking to establish themselves in a home, they expect the available technology to help support their needs.”

***

Due in part to its location, Sunny View is heavily invested in tech, using it for everything from live streaming Sunday services from a nearby church to Wii bowling tournaments and programs like Rendever’s virtual reality. And they’re paying for it: The community paid roughly $150,000 to $175,000 for all their tech systems, as well as ongoing rental fees of about $10,000 a month.

But according to many, it’s worth it. “It’s not just giving people unique immersive experiences, but shared experiences,” says Park. “If a couple wants to see the moon in Paris or a village near Tokyo, it allows people to talk about what they’re seeing and recall it. It’s a great way of stimulating conversation, fostering engagement and evoking past memories. It’s not about Mario Go Kart.”

Sunny View also deploys a movie system called 3Scape that provides 3D-filmed content rooted in reminiscence therapy. Films are designed to spark cognitive function, lessen depression and evoke happiness. One film about a young boy who lives on a farm seems so real, the fields and farm animals seem to stop right at your feet.

“It’s like you’re really there,” muses Chia-Liang Li, a jovial man of 93 whose memories of his youth flooded back while watching the film. “When I was 10, I lived on a farm. My father was a farmer.”

The senior living center also has the system It’s Never 2 Late (iN2L), which consists of large touch screens with big icons that seniors press to connect with the grandkids by video chat, visit the Louvre, read online newspapers from their hometowns, conduct a virtual orchestra and watch movies, all adapted to their abilities.

“People want to be connected and relevant,” says iN2L’s president and co-founder Jack York. “These people are doctors and lawyers and welders and teachers, and they can be treated like 10year-olds with the kind of programming some places have. We have easily accessible content partitioned to deal with wherever a person is cognitively, while making it easy and enjoyable for them.”

At Sunny View, residents also have access to CyberCycle — an interactive recumbent exercise bike that lets riders race against other virtual bikers — and Paro, an FDA-approved robotic baby harp seal designed to stimulate brain activities of people with cognition disorders. The idea is to alleviate anxiety, depression and loneliness, says its Japanese developer, Takanori Shibata. With sensors that react to light, touch, sound, temperature and position, the white-furred creature squeaks, coos, blinks and moves, allowing it to deliver the benefits of pet therapy without the logistics of using real animals.

“If someone is agitated or restless or wandering, we use Paro to lessen anxiety,” says Park. “It soothes and calms down and it just takes minutes. Meds take at least half an hour to kick in.”

But more than anything else, what seems poised to transform the senior service industry is voice-first technology. Of Sunny View’s 119 residents. about half have adopted Alexa.

Neubieser loves his Alexa. “If I say, ‘Alexa, play music,’ she plays music. If I say, ‘Alexa, what time is it?’ she’ll tell me. If I say, ‘Alexa, turn off light,’ she’ll turn it off. She’s like a good friend,” he says.

* * *

Age-tech is also employed to prevent falls, a priority in senior living facilities. The National Council on Aging reports that falls are the leading cause of injuries for older Americans and result in more than 2.8 million emergencyroom visits annually, including over 800,000 hospitalizations and more than 27,000 deaths.

Sunny View has installed smart lighting tied into Alexa. “We had reports of people saying, ‘I feel safer now. I’m able to light my way to the bathroom in the middle of the night now,’” says Park, who calls Alexa “a fall-risk mitigator.”

SafelyYou, which came out of the Berkeley Artificial Intelligence Research Lab, is deployed in more than two dozen senior communities across California, including the Parkview in Pleasanton and the Trousdale in Burlingame.

Cameras are placed in seniors’ rooms and staff is alerted when a fall occurs. The team then conducts a review of the real-time video for clues as to how it happened — especially helpful when a resident can’t explain firsthand why he or she fell.

“The system constantly records, but for privacy reasons, there is no screen that can be watched,” says Sylvia Chu, executive director at the Trousdale. “Everything not fall-related is deleted automatically. If it detects a fall, that piece will be recorded and a signal sent to the front desk, which must answer the call.”

“We have post-fall huddles discussing what happened and how it happened and (we think), this person has fallen twice on the corner of the bed, so let’s change the direction and orientation of the bed,” says Therese ten Brinke, director of strategic initiatives at Eskaton, which operates three care centers and a dozen residential facilities in California, including the Trousdale. “And then we see those residents are no longer falling.”

Marco Santos, vice president of clinical operations at Carlton Senior Living in Concord — which runs 11 senior communities in California — says the technology has reduced falls in Carlton facilities by 31%. “It was the only tech available to us besides wearables,” says Santos, “and we’re not big fans of that.” (Among other reasons: residents take them off.)

Some communities have also introduced smart sensors, with mixed results: The Rhoda Goldman Plaza in San Francisco tested them in its memory-care unit but dropped them after the system seemed only able to signal that someone was getting out of bed.

Eskaton partnered with startup K4Connect to integrate smart sensors into apartments using devices such as lights and thermostats. The company rolled out social tablets with the K4Connect app that residents could also use to check the menu, access community announcements and connect with family members, but they didn’t do so well, says ten Brinke. “There was a steep learning curve, and sometimes there were some barriers for someone living with forgetfulness and lack of dexterity.”

When one resident with Parkinson’s disease said he needed to control the sensors with his voice, K4 Connect integrated Alexa through its app and now residents can speak their commands.

Not all senior living homes have embraced technology with equal measure.

“We use it very lightly here,” says Milford of the Rhoda Goldman Plaza facility. “Its adoption in a group of older adults whose average age is 88 is not as deep as it will be in even a few years. And when a technology is offered, it needs to be introduced thoughtfully, over time with plenty of training,” she says. “You can’t just hand them an iPad and tell them they can order dinner or do this or that. While tech is very attractive to the adult children, most seniors will put the iPad down because you have to train them over and over.”

At the Goldman facility, tech mostly consists of a weekly class on smart devices and limited use of Alexa and ElliQ, a talking social companion robot for older people that can arrange rides, remind them to take their medication and let them know when a new picture of the grandkids arrives.

“We’ve introduced Alexa and ElliQ on a case-by-case basis,” Milford says. “Some like that they can program their music to their own tastes. Others felt very uncomfortable because they felt they were being watched.”

Milford says the facility is open to tech, “but not to the point where it replaces staff members. There’s rampant loneliness. You have a phone, but that is not a life force. You’re losing your opportunity of having real connections with a real person and this is something tech can never replace, and there is something that is lost when it happens.”

While tech may not universally boost quality of life, it can revolutionize some lives.

When Anne Davis, 88, began losing her sight to macular degeneration, she was unable to read and in despair.

“It’s pretty awful not to be able to see,” says the former faculty member at UCSF’s School of Nursing, who lives in the San Francisco Towers retirement home. Now, not only can she read, she just sent a publisher a book proposal she composed on her iPad. The magic? IrisVision’s goggles, comprising a Samsung smartphone, Gear virtual-reality headset and software that compensates for what she can’t see naturally.

The difference tech has made for Davis is astounding. But perhaps its greatest value is its potential to keep seniors independent for longer.

Castro Valley’s Frank Rios, 77, was desperate after losing his sight from leukemia but wanted to stay at home. The goggles changed everything.

“Now,” says Rios, “I turn to my partner and can actually see his visual expression. That’s something I hadn’t seen in three years.”

Mandy Behbehani is a freelance writer in the Bay Area.

“With the increased penetration of smart devices into people’s homes, (people) are wanting to see these things in senior living communities. When they’re looking to establish themselves in a home, they expect the available technology to help support their needs.”

Davis Park, executive director of the Center for Innovation and Wellbeing at Front Porch, which owns senior communities