Genetic mysteries of the biggest trees

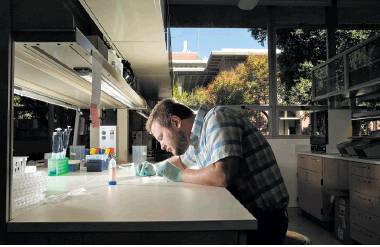

Scientists probing primeval forests for survival traits

By Peter Fimrite

Redwood trees, those ancient living monuments to California’s past, are as mysterious to science as they are magnificent, so a team of researchers led by a San Francisco conservation group is attempting to unlock the genetic secrets of the towering conifers.

Scientists affiliated with the nonprofit Save the Redwoods League are attempting for the first time to sequence the genomes of coast redwood trees and their higher-elevation cousins, the giant sequoias, a complex and expensive undertaking that experts hope will help preserve the trees’ ancient groves as the climate changes over the next century.

The five-year, $2.6 million Redwood Genome Project is the most intensive scientific study ever done on the state’s famous primeval forests. The goal is to enable scientists to maintain forest resiliency and genetic diversity by choosing the most robust, adaptable genes when planting or doing regeneration or habitat protection work.

“This is by far the greatest challenge that anyone has taken on (relating to redwoods), and it has an infinite number of uses,” said David Neale, a UC Davis plant scientist and the projects’ lead researcher. “These conifers are very, very old and have been accumulating DNA for millions of years.”

Sequencing the coast redwood genome will be especially difficult, he said, because it is 10 times larger than the human genome. Coast redwoods, for instance, have six sets of chromosomes compared with two for humans, an evolutionary adaptation that researchers believe helped the trees adjust successfully to changing conditions over thousands of years.

Other conifer species have been sequenced, including Douglas fir, sugar pine and Norway spruce. But like humans, those trees only have two sets of chromosomes, Neale said.

“Coast redwood will be the world record holder in terms of the largest genome sequenced when it is completed,” he said.

Neale hopes to produce genome sequences for both species by next year. Once the genetic blueprints are available, biomedical engineers at Johns Hopkins University will do a computer analysis, which will allow researchers to develop genetic variation models for each forest and develop and implement restoration projects, according to the plan.

The work is important because old-growth trees once covered mountainous regions in the Sierra Nevada range and up and down the California coast all the way to the Oregon border. Starting in the 1850s, loggers began cutting them down, including a massive stand in Oakland that researchers say might have contained the largest trees in the world.

In all, about 95 percent of California’s old growth has been wiped out over the past century-plus, a staggering loss when one considers how old many of these trees were. The tree-ring record taken from the last remaining old-growth trees — a historic catalog used to track climatic and weather events — can now reliably be traced back to the year A.D. 328.

One tree in Redwood National and State Parks, near Crescent City (Del Norte County), is 2,520 years old. The largest of the Sierra sequoia giants, which generally live longer than their coastal cousins, is 3,240 years old, according to a Save the Redwoods League study.

North Coast redwood trees were used to rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake and fire, but even then, people were alarmed about the clear-cutting of the ancient forests.

The Save the Redwoods League was formed in 1918 to protect the imperiled trees, but they kept falling to the ax until environmental activists stopped the logging of old-growth forests over the past few decades.

“At this point, we have protected nearly all of the old-growth groves that remain on Earth, but there’s so much more we can do for the recovering redwood forests that surround and sustain them,” said Sam Hodder, president of the Save the Redwoods League. “Much of our work is now shifting to forest restoration and finding new ways to transform the previously cut-over redwood forests into magnificent old growth.”

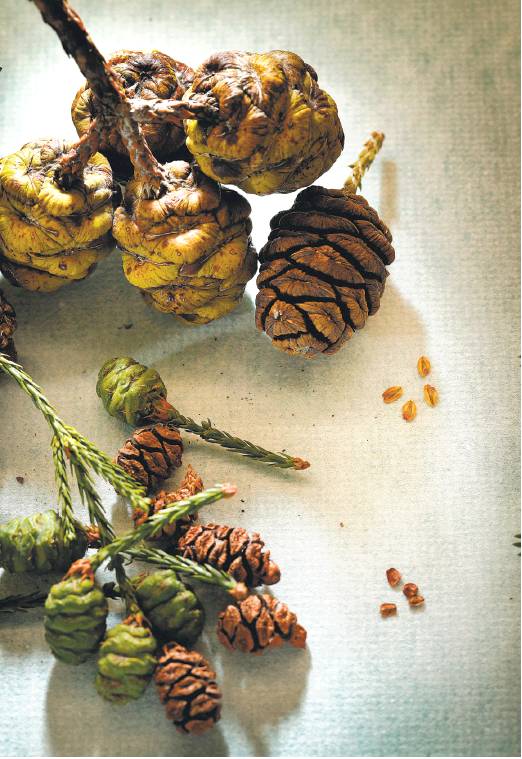

Less-sophisticated genetic testing has already dramatically improved scientists’ understanding of the trees. Scientists, for instance, long believed that “fairy rings,” the circles around the stumps of chopped-down redwoods, were clones of the original trees, but testing has shown that is not always true.

Testing of core samples has also shown that northern and southern redwoods are genetically distinct and that some giant sequoias, like the Placer County Big Trees Grove, a forest above Auburn that contains only six mature trees, may be inbred, a condition that researchers say is just as unhealthy for trees as it is for humans.

In addition to narrowing down characteristics of the trees to figure out which ones adapt best to changing conditions, like drought and wildfire, the genome study will be aimed at figuring out how to use the trees’ hereditary attributes to help both the atmosphere and the creatures that depend on them.

“Our concern is that we may have lost some of the genetic diversity of some of our forests,” said Emily Burns, the director of science for the Save the Redwoods League. “Could our old-growth forests be more vulnerable to climate change, and other stressors, like drought, because of a lack of genetic diversity? We don't know which trees are the ones that are best suited for the future, but we want to make sure that when we do that restoration work we are protecting that genetic diversity.”

Restoring the forests has taken on more urgent importance than ever, Burns said, because old-growth redwoods store three times more carbon than other types of trees and have unique decay-resistant qualities that allow them to hold carbon even after death, thereby keeping climate-warming gases out of the atmosphere. Their many limbs and branches also sustain other plants and wildlife, many of which live high in the tree canopy.

“We need to find which trees are more likely to develop big limb systems early on in their lives, so that we would be able to cultivate those trees in the forest to directly support wildlife,” Burns said.

Curiously, scientists have discovered from core samples and tree-ring studies that old-growth redwood trees along the California coast and in the Sierra are in the midst of a growth spurt that has accelerated over the past few decades.

The increased growth is believed to be happening because there is more sunshine than in the past along the coast and more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. A 2010 study documented a 33 percent decrease in the amount of fog and cloud cover along the Northern California coast since the early 20th century.

But that growth can’t be counted on to last forever, Burns said, and the genome study is an opportunity to learn whether unforeseen genetic dangers could befall redwoods if a climate tipping point is reached in California.

“Right now that information is almost completely hidden from us,” she said. “This blueprint is just going to open our eyes and help us protect and conserve these forests far into the future.”

Peter Fimrite is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: pfimrite@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @pfimrite