Mr. Wilson’s second act

After his sight started to fail, trumpeter at the top of his field came to see music in a new way

By Jill Tucker

Tim Wilson steps onto the small stage platform, raises his baton and asks the 100 or so students seated before him to settle down. Music, he tells them, is painted on a canvas of silence — a lovely metaphor that has no effect. The October dress rehearsal for the middle school band’s first concert of the year is not going well.

Wilson waits. The hum of conversation continues, punctuated by an occasional clarinet’s revolt or trumpet’s yawp. The canvas at Lovonya DeJean Middle School in Richmond is rarely silent. So the music teacher waits some more.

He’s not supposed to be here, in this multipurpose room that doubles as a cafeteria, the smell of tuna salad and chicken tenders lingering in the air. He was a virtuoso, a tuxedo-clad trumpeter who moved opera house crowds and commanded a rare six-figure salary.

Until he started to go blind.

“They are accomplishing music they never thought they could do. They are musicians now.”

Tim Wilson, after successful spring concert at DeJean Middle School

Now, he’s Mr. Wilson the music teacher. Instead of playing Puccini’s “La Bohème” at San Francisco’s War Memorial Opera House, the 58-year-old maestro is working up to 14 hours a day coaxing “Jingle Bells” out of beginners and pouring much of his life savings into bringing music back to a school where 95 percent of students live in poverty. If he can take kids who can’t play a note and teach them a song, Wilson believes, they will not just feel successful, but see new possibilities everywhere in their lives.

It is his fourth year of teaching at DeJean, of testing that belief. And, though he doesn’t know it yet, it also will be his last.

So he stands on the platform, this unconventional man with disheveled hair and bloodshot eyes, a black apron on his waist to hold pens, bathroom passes and good-behavior raffle tickets, and waits for his students to quiet down. Only when the chatter finally abates by an almost imperceptible decibel does he begin to count: One and two and three and ...

The students play. The notes aren’t perfect. A trumpet is flat, and a trombone is off by an octave. But the song is unmistakable: The itsy bitsy spider is climbing up the water spout.

When the music stops. Wilson jumps off the stage, then leaps again, spinning in a circle, his glasses bouncing. His five band classes, mostly students who picked up an instrument for the first time five weeks earlier, have played a song together.

“It’s working, it’s working!” he yells. “It’s never been done here before!”

Here is a school where 3 out of 4 students test below grade level. Where most are surrounded by poverty and frequent violence, including a clarinet player who sometimes stops to pray at the spot in her front yard where a man was shot dead.

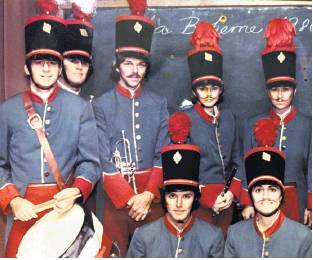

Here is a school of 530 students in a working-class neighborhood of modest homes, churches, fast-food joints and auto shops on Richmond’s main artery, Macdonald Avenue, just west of Interstate 80. It is 17 miles from the orchestra pit at the San Francisco Opera, where Wilson spent 22 years surrounded by bejeweled patrons and performers with perfect pitch, where he accompanied legendary tenor Placido Domingo more than 30 times. In the Opera off-season, he played on film soundtracks at George Lucas’ Skywalker Ranch in Marin County. His favorite was “Predator 2.”

He isn’t supposed to be here, but here he is, reveling in a nursery rhyme.

* * *

He remembers the day he noticed something was wrong. It was early 2003, and he was in the orchestra pit at the opera house. He realized he couldn’t see the notes on the sheet music as clearly as he could before the Opera’s winter break.

As the principal trumpet player for the orchestra, he was an elite musician in a job that required grueling practices and frequent performances. A lifelong perfectionist, Wilson would stay long after the audience had filed out to run through a particular passage again and again, ironing out problems imperceptible to the average ear.

But now the notes on the page looked fuzzy. He booked an appointment with his eye doctor.

For most people with healthy vision, a fluid called aqueous humor cycles through the space between the eyeball’s lens and the cornea, some draining out as more flows in to maintain pressure. If the aqueous humor can’t drain properly, pressure builds and can damage the optic nerve, causing glaucoma. Annual eye exams can detect it in the early stages, but if left unchecked, the condition can damage vision and lead to blindness. Wilson had left it unchecked.

Medicine and surgery can mitigate the effects, but some things can make it worse. Like blowing into a trumpet.

“When I play trumpet, the pressure goes up in each eye,” Wilson says.

The ophthalmologist gave him a choice: Keep playing and risk going blind, or stop and save some of your sight. If you want to see your grandchildren, the doctor said, you’d better stop. So after playing millions of notes for the “Macbeths” and “Madame Butterflies,” he quit the Opera.

It was, he says, the responsible choice.

As he tells the story 14 years later, tears pool in his eyes. It’s September 2016, and he’s standing in his empty classroom. DeJean is hosting back-to-school night, and none of his first-period parents has shown up.

“I played an instrument, and it moved people,” he says. “I spoke to people’s hearts through my music.”

For years after he left the orchestra, he cried every time he heard the first bars of classical music on a car radio. When he returned to the opera house, sitting in the audience, his fingers pressed imaginary trumpet valves on his armrest. Now, seven surgeries later, Wilson still isn’t supposed to play his trumpet, but he keeps one at his feet as he teaches so he can demonstrate for his students, playing just a handful of notes at a time.

With still no parents on hand to hear his back-to-school spiel, he picks up his trumpet and starts to play. It’s a haunting tune, from the opera “A Streetcar Named Desire,” which premiered in San Francisco with Wilson on principal trumpet. The passage is from the final moments of the final act, where his playing echoed the story’s tragic character Blanche as she asked, to an empty room, “Who am I?”

Wilson puts the trumpet back in the case.

“My identity, to be able to speak through an instrument, was gone,” he says.

He was 45 when he left the orchestra, and he didn’t know who he was without a horn.

* * *

Wilson cannot remember a time without music. Growing up in Scotts Valley (Santa Cruz County), his parents were professors at Bethany University, a now-closed Christian liberal arts college. His mother, a pianist, taught music; his father, who played trumpet, taught history. Tim started piano lessons at age 3, six years before he first picked up the trumpet in fourth grade.

Music was not just a given. It was nonnegotiable.

“As long as you live in my house,” his mother told him, “you will brush your teeth every day and you will practice.”

So he practiced. By eighth grade, his talent had surpassed his trumpet teacher’s. He started taking lessons from Don Reinberg, then principal trumpet player for the San Francisco Opera. At 17, he had his first job at the San Jose Symphony. Then came the Oakland Symphony and, by age 21, the third trumpet seat in the San Francisco Opera Orchestra.

Just over a decade later, he was first chair, where his uncommon focus set him apart.

“Everyone has the will to win,” says David Ridge, a former colleague who still plays bass trombone for the Opera. “Not everyone has the will to prepare to win.”

Then, suddenly, his career ended. With the prospect of decades sprawling before him, he threw himself into triathlons, hitting the pavement and pool with the same urgency he’d brought to the scores of Mozart or Puccini. He would overtrain, pushing himself to mental and physical exhaustion.

Eight years into this reluctant retirement, he got an email from the Department of Secondary Education at San Jose State after he had inquired about continuing education programs. Become a teacher, it said. Three days later, he was taking classes toward a teaching credential. It was there that a professor showed Wilson and his classmates a documentary about the Venezuelan music education program El Sistema.

The publicly funded program, which has expanded to several countries, now teaches hundreds of thousands of impoverished children to play music. Starting as young as age 2 or 3, they spend hours nearly every day singing, reading music and learning an instrument. Some of its alumni, such as Los Angeles Philharmonic Director Gustavo Dudamel, have gone on to international acclaim.

El Sistema teaches music, but it’s really about changing the fate of children.

“The most miserable, the most tragic thing about poverty,” El Sistema founder José Abreu has said, citing Mother Teresa, “is not the lack of bread or a roof but the feeling of being no one.”

The documentary stirred something in Wilson.

“That’s social justice mixed with music,” he remembers thinking, “and I can do that.”

He would earn two credentials, in math and music. With his opera pedigree, he would have been a strong candidate at any school. But he wasn’t looking for a career or even a paycheck. He was looking for a challenge.

He applied to a handful of schools, and interviewed at a few, including DeJean, which needed a math and music teacher.

“I interviewed,” he says, “and felt like there was a need I could fill.”

* * *

Eighth-grader Akasha De-Aguero walks into Wilson’s music room a few days after the school band’s first concert, the one with the rendition of “Itsy Bitsy Spider.” She drops her backpack and pulls her clarinet from her locker. Her hair is shaved on the sides, with the longer strands on top pulled into a dyed bun. Sometimes it’s orange or red. Today it’s blue.

Akasha is in Wilson’s fourth period advanced band class, the only one that has students with music experience. She has been playing since third grade. She wanted to play the drums, but a teacher at her Oakland elementary school stuck a clarinet in her hands instead.

“It was hard. There were too many buttons for me,” she says. “I’ve been stuck with it ever since.”

Two years ago, she moved from Oakland to Richmond and into a shelter, after her family was evicted from their home. She shares a room with her mom and sister with a bathroom down the hall. Her dad has to live separately, at a nearby shelter for men.

When she practices the clarinet — quietly, so as not to disturb others through the shelter’s thin walls — she prefers the deep, reverberating notes at the bottom of the scale. She can feel them in her chest. They remind her of her home in Oakland.

“We used to have speakers on each side of the TV,” she says, and when they were cranked up, “the whole house shook.”

She wants to join the Air Force someday. She wants to fly. So far, the closest she’s come, she says, is putting her face out the car window and closing her eyes.

Akasha pulls out her clarinet and sucks on the reed to soften it before playing. Wilson, meanwhile, is counting off seconds, willing his students to get their instruments out and start making music. The fall concert was a success, but the next performance is in December, and Wilson knows he will need every day to prepare.

One student can’t get into her instrument locker, so Wilson jogs back to the instrument closet to open it with a key. He rarely walks, instead running or speed-walking with awkwardly long strides. Sometimes he trips, either because of his limited vision or because he simply isn’t paying attention. He darts about as if there’s a thought bubble over his head: So much to do, so little time.

“I get emails from him at 3 in the morning,” says Darrell Perry, Wilson’s full-time aide who coaches the marching band. “He’s a driven man.”

Perry describes the music teacher as “tenacious,” but that’s Wilson’s word, one he includes in his constant motivational mantras. Anyone who spends a few minutes in his class will hear him implore his students to use “tenacious engagement.”

“Confidence and effective effort lead to competence,” he instructs, repeatedly. “Failure and difficulties are feedback.”

A student wanders in late. While he marks her tardy, Wilson hits her with another catchphrase: “Being on time shows you care for your community.”

“I don’t give a f— about my community,” she growls under her breath.

Teaching his students music is arguably the easiest part of Wilson’s job at DeJean. Persuading them to try, to fail, to believe they can learn and master a difficult skill if they put in effort, that’s the difficult part. Many have experienced devastating trauma, family dysfunction, poverty. He wants them, he says, to have a “growth mindset.”

“They are born into their lives, they do not choose their lives,” Wilson says. “But if I say, ‘I am with you and the deck is stacked against you, but I believe in you and I will help you to the best of my ability,’ then they’re my teammates, making the world a better place.”

At the moment, though, his team is in disarray. The lesson plan is scheduled to the minute, and they’re behind. They have several songs to learn, and they often have to take them in small steps — one note, then one measure, then one line. Two more students wander in late. A percussionist needs mallets, sending Wilson rummaging through bags and boxes, before realizing he’s out. He will have to buy more.

* * *

The philosopher Plato once said, “I would teach children music, physics, and philosophy, but most importantly music, for the patterns in music and all the arts are the keys to learning.”

More than 20 years ago, researchers found that music majors were more likely to get into medical schools than biology majors. Since then, study after study has shown the benefits of a music education.

It’s been linked to stronger attendance and graduation rates, higher IQs and SAT scores, and better behavior. Studies have found benefits in self-esteem, hand-eye coordination, memorization and creative thinking. Those in a school band were found to have the lowest lifetime use of alcohol, tobacco or drugs when compared with those participating in other school activities.

Yet across the country today, an estimated 1.3 million children have no access to music in their schools. Only about a quarter of African American and Latino children receive any arts education, compared with about 60 percent of white students, according to a 2008 survey by the National Endowment for the Arts. Wealthier parents often rent or buy instruments and pay for private lessons while bolstering PTA budgets to support the arts. Those in lower-income communities often cannot.

At DeJean, where 90 percent of students are black or Latino, there was no music program for years. When the school was built 14 years ago, replacing a long-shuttered high school, it included a music room shaped like a grand piano. But when the recession hit, music was cut. The school’s few dozen instruments were stored away.

Wilson found them when he arrived in fall 2013. At half his Opera salary, he began teaching four periods of math and one class of music for beginners. He knew he had a daunting task ahead — teaching 30 novices how to play the variety of instruments needed for an orchestra.

The thing to do, he figured, was to teach everyone guitar, which would erase the need for students to read notes on sheet music. The problem? The school didn’t have any guitars.

“I asked myself, if I had kids here, what would I want for them?” he says. That’s when Wilson started spending his own money.

Teachers routinely shore up classroom supplies with their own funds, but this was different: That year, he bought 100 guitars: 50 acoustic, 50 electric. The next year: 80 drums for a drum line.

In three years’ time, he would buy most of the students’ instruments, from triangles to several sousaphones, primarily from Goodwill auctions. He also paid for ergonomic chairs, music stands and sheet music, microphones and speakers, and covered repair costs for anything that broke.

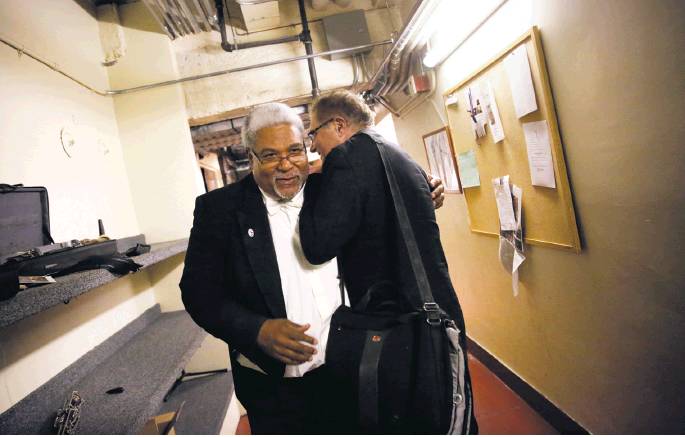

“I almost started crying. This was the kind of music happening in other communities. It was like they’d been playing for 10 years.”

Principal William McGee recalls observing Tim Wilson’s music class when the students were playing

This school year, he began writing paychecks, too: $600 each week to Perry, his full-time assistant, as well as $150 weekly for a percussion aide and $6,000 each semester for a clarinet coach.

It still wasn’t enough, at least in his mind. Last summer, he organized a band camp, hiring five instructors for a month’s work. He figured he’d need at least 20 students to make it worthwhile, but when only 14 showed up, he didn’t have the heart to cancel it.

So he added it to his prolific tab — by his own estimate, $300,000 and counting.

Samantha Hernandez attended band camp. The 13-year-old, who goes by Sam, has lived in Richmond her whole life. She was 10 when a man was shot and killed in her front yard.

“I sometimes go to the spot and just pray for his life,” she says.

She used to hear a lot of gunshots in her neighborhood, though not so many now. Crime has fallen in recent years in Richmond, which once earned a national reputation as a murder capital.

There are growing signs of improvement, and gentrification, in the city of 110,000. Still, 1 in 4 residents lives in poverty. Last year, 24 people were killed, including a 14-year-old high school freshman shot during the school day right behind DeJean.

For Sam, Richmond is just home. And at DeJean, band is her favorite class, a safe space where music calms the social savagery of middle school.

“Sometimes I’m really mad because these girls are being mean to me and they want to fight,” she says. “When I come to band, everything changes. It makes me think, ‘I’m here. This is my time.’ Band is more important than these girls.”

* * *

It’s December, and the music coming from Wilson’s classroom features fewer squeaks and squawks, more flutes in sync, as students note-read through complicated songs with irregular rhythms. At twice-weekly marching band practices, Perry teaches routines that involve forward dips and about-faces while half the band goes one way and half the other.

By the time students reassemble on the multipurpose room stage for the winter concert, they are proficient in the six songs printed on the program.

Wilson spent hours creating the multimedia concert, interspersing instructional videos about Kwanzaa and Hanukkah with performances of “Adeste Fidelis” and “Jingle Bells.” But as he stands onstage, baton in hand, the racket from the mostly student audience echoes.

Only a handful of parents are here. Wilson decided earlier in the year to schedule concerts in the afternoons, during school. Most parents couldn’t make evening concerts either because they were working, didn’t have transportation, or had other issues. At least with the students here, about half the seats are filled.

“Please, stop talking,” Wilson exhorts the audience. “Just listen.” Six times he asks. “Music depends on silence,” he says. Twice more, he pleads for quiet before giving up and cuing the band.

Wilson’s wife and mother are also here. He met his wife, Deanne, in high school band. She played the flute, and she didn’t like him at first. He was a “pompous jerk.” They have been married 36 years.

Her husband is “super passionate” about everything he does, she says. And while he might appear flustered, he’s unflappable — he delivered their second son in the backseat of their car at a San Francisco oil change station on Valencia Street in 1991.

“He sees a problem, he’s going to fix it,” she says.

In other words, she wanted a trip to Hawaii. He funded a summer band camp.

“He doesn’t give up on them,” she says of his students, “and he doesn’t give up on the music.”

Wilson’s mother, Kathyrn Wilson, pivots in her chair at the concert, a stern expression frozen on her face. Her son has given so much to this school, and the audience appears unimpressed. She worries about him.

“He’s always been driven; it’s his personality,” she says. “I’ve always said to him, ‘If there’s anything you can work on, it’s knowing you can’t give 200 percent.’ ’’

In truth, Tim Wilson is tired. He hasn’t felt well in weeks. After the performance, his classroom empty, he says he feels like he used to when he overtrained for triathlons.

* * *

It rains through January, and it’s raining again the first week of February as Wilson prepares for the day’s first class. He grimaces as he bends to pick up a piece of paper. There’s something wrong with his heart, he says, and some other health issues he declines to discuss in detail. “It’s not good,” is all he’ll say.

As his first-period students file in, Wilson hides his fatigue. He trots over to help open a locker, to adjust a mouthpiece. He reminds his students again about “tenacious engagement.” But a few minutes before the end of class, he decides it’s time to tell them what he’s known since the end of December:

“You guys have come so far, and it’s not because of me,” he says. “This music program is you.”

He’s having health issues, he says, and leaving DeJean at the end of the school year is the responsible thing to do for himself and his family. The principal will find them another music teacher. It is a message he will repeat, while betraying little emotion, in each of his four other classes this day.

The room is unusually quiet as a clarinet player raises her hand.

“You paid for all the instruments,” she says.

“Yes, I did. They’ll stay here,” he says. “They’ll stay with you because it’s your music program.”

The students, including Akasha, appear mostly unfazed. Like many, she’ll be heading to high school next year, where she’s already signed up for advanced band. Her mother, Elaine DeAguero, however, is heartbroken at the news that DeJean will be without its singular music teacher.

“He knows what our situation is,” she says of the family’s homelessness. Wilson not only let Akasha borrow a portable keyboard with headphones for the year so she could play at home, but gave her rides to and from performances and events, stepping up the help after her bus stopped running in the evenings.

More than any of that, the mother says, he gave Akasha music.

“Life in general would have been hard if she didn’t have that outlet of music,” DeAguero says. “It really grounds her and gives her something that is all hers.”

Earlier in the school year, the mother says, Akasha played “Happy Birthday” on clarinet for her father at a picnic in the park.

“She didn’t have anything else to give him,” she says.

DeAguero laments what she calls a “huge and tragic loss for DeJean.” But Akasha doesn’t think about what it means for the school. She thinks about what “Mr. Wilson” has meant to her.

“He’s the teacher I’ll always remember,” she says. “The one I’ll tell my kids about.”

* * *

The day of the spring concert, Wilson is feeling better, thanks to healthier food and a doctor’s care. He’s tempted to take back his resignation. It’s been six weeks since he told students he was leaving.

“I just want to lay down my life and keep this going,” he says. “But I can’t.”

He’d like to teach again, if his health holds up, but maybe only math rather than music. He’s decided to apply for jobs closer to his home in Corte Madera, just in case. He wants to see Perry remain at the school without him. He’s started an online fundraising campaign to pay his salary.

“They are owed more support than they get, because they face more obstacles than they deserve,” Wilson says. “I did what I could.”

But why, he’s asked, why did he do it — the 14-hour days, the physical toll, the $300,000?

Wilson’s answer is straightforward: Because he could. He has lived a privileged if not a charmed life, he says, and wanted to give back. Once he became a teacher, he threw himself into the role, just as he always has. He doesn’t see what he’s done as noble, just logical.

He thought he could make a difference. He believes he did. He has no regrets.

“They are accomplishing music they never thought they could do,” he says. “They are musicians now.”

William McGee, the DeJean principal, agrees, though he wishes he had forced the music teacher to give a little less, to take care of himself a little more. He regrets that he didn’t force Wilson to go home earlier more often. And he doesn’t want him to leave.

Instead of seeing a troubled school with low test scores, people are now looking at DeJean as a place where students leave campus with instrument cases in their hands, so they can practice at home. A few weeks earlier, McGee had walked into Wilson’s room to observe a class, as he often does with his teachers.

“I almost started crying,” he says. “This was the kind of music happening in other communities. It was like they’d been playing for 10 years.”

The principal worries what will happen next year — how he will keep the music going. He’s already looking for someone to fill Wilson’s shoes. He’d settle for a qualified music teacher.

That concern is pushed aside as the spring concert begins and Wilson once again mounts the platform in the multipurpose room, his back to an audience comprised of cafeteria workers cleaning up after lunch, some parents and a few dozen students.

As he did six months earlier, he asks his band for silence and then the audience for the same. This time, save for a few whispered conversations and giggles, they comply.

Wilson raises his baton, and the band members lift their instruments in response. He smiles at his 80-piece band and drops his hand, beckoning the first notes of the brass-heavy “Star-splitter Fanfare.” Then comes a classical baroque piece by George Frederic Handel, African folk songs and two American blues tunes. “Itsy Bitsy Spider” is a distant memory.

The finale arrives 20 minutes later with “Jus’ Plain Blues,” a toe-tapping melody of quarter notes. Mid-song, Wilson reaches into the open instrument case at his feet and lifts a silver trumpet to his lips. His old trumpet.

The piercing notes fill the cafeteria, silencing the now wide-eyed students in the audience who, just moments before, had been bent over their phones and in conversation with friends. Wilson’s eyes are closed and he’s swaying, his head tilted back, his foot stomping as his students play 12-bar blues backup to his solo.

He is playing the high notes, the ones he’s definitely not supposed to play. He plays them with abandon.

And then, with a sweep of his hand, it’s over. The old musician and the many young ones beam at the loud applause. As they bow, they hear a single word. Wilson has heard it before, but this time it’s not for him.

The audience is demanding an encore.

Jill Tucker is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: jtucker@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @jilltucker

“They are owed more support than they get, because they face more obstacles than they deserve. I did what I could.”

Tim Wilson, talking about his students

v Watch a video that accompanies this story at www.sfchronicle.com