Limits on zoning cited for Marin’s high segregation

By J.K. Dineen

A new UC Berkeley study showing that Marin County leads the Bay Area in segregation didn’t come as a surprise to Phil Richardson — or, for that matter, to other developers who have struggled to get housing built in the North Bay county.

Since 2004, Richardson has been trying to build an apartment house on a 1.25-acre site near the intersection of Camino Alto and East Blithedale Avenue, a busy crossroads near a Whole Foods, a post office and the Mill Valley Recreation Center. It’s one of the few undeveloped lots in town.

Three times between 2004 and 2019, Richardson submitted plans, and three times the city turned him down, as neighbors opposed the project, saying it would snarl traffic and alter the character of the neighborhood. Now Richardson is back with a fourth proposal, a 25-unit building that would include 12 affordable apartments. He hopes the recent regional focus on the affordable housing crisis will change the outcome this time — but he is not optimistic.

“There is a lot of verbiage around affordable housing, but not much action,” he said. “It’s a county controlled by people who feel affordable housing is not appropriate in Marin County.”

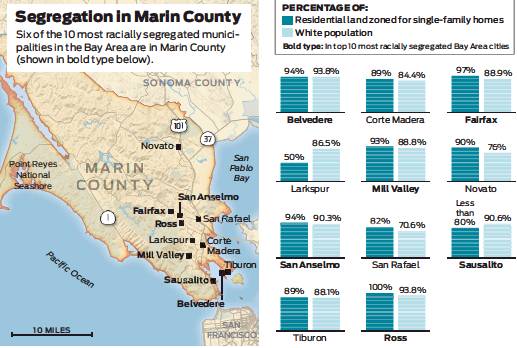

The report from UC Berkeley’s Othering & Belonging Institute found that six of the 10 most racially segregated municipalities in the Bay Area are in Marin County. Using data from census tracts, the institute calculated segregation in each of the Bay Area’s 101 municipalities, categorizing demographics into five categories — Latino, white, African American, Asian and other. The study ranked cities and towns by what it termed “intermunicipal segregation” — or the “segregation of the residents from the larger region.”

The top 10 includes Ross and Belvedere, where whites make up more than 90% of the population, as well as Sausalito, San Anselmo, Fairfax and Mill Valley, which all have white populations of more than 85%. As a whole, the nine-county Bay Area comprises 59% people of color. Rounding out the 10 top are Woodside, Portola Valley, Cupertino and East Palo Alto.

While multifamily development doesn’t guarantee an integrated neighborhood, the study shows that in a wealthy county like Marin, where the average home price is just under $1.3 million, strict singlefamily zoning all but ensures that communities will remain wealthy and white.

Most of Marin County is zoned for single-family homes, and the communities with the highest percentage of singlefamily home zoning tend to be the whitest. Ross, which is 93.8% white, has 100% of its residential land zoned for single-family homes. San Anselmo is 90.3% white and excludes multifamily buildings on 94% of its residential land.

Communities that allow more apartment buildings are more diverse. San Rafael, for example, allows apartments on 18% of its residential land, and its population is nearly 30% people of color. Marin City, which was settled by African American shipyard workers excluded for decades from buying or renting in other Marin communities, has the most multifamily housing in the North Bay, with more than 600 deed-restricted affordable apartments. It is also the most diverse — Marin City is 40% Black, 13% Latino, 7% other minority groups and about 40% white. Next door, Sausalito is 92% white and just 1.5% black.

“In diverse areas like the Bay Area, if you have all-white communities, what that means is you have an all non-white community somewhere else,” said lead researcher Stephen Menendian, assistant director of the UC institute. “Marin County regards itself as a progressive place, but it doesn’t live up to its values. You can’t deny it if you look at the data.”

Multifamily developers attempting to build in Marin are stymied by strict zoning as well as well-funded neighborhood opposition. In late October, Novato city leaders declined to pursue a rezoning that would have allowed highdensity affordable housing just north of downtown near the SMART train station.

In Corte Madera, residents have opposed county plans to buy a hotel to convert into housing for homeless people. In unincorporated Strawberry, neighbors are fighting a project that would allow North Coast Land Holdings to build 234 units at the former Golden Gate Baptist Theological Seminary property, 47 of them affordable.

The county’s two workingclass neighborhoods with concentrated nonwhite populations are Marin City and the Canal neighborhood of San Rafael, largely home to Latino households.

Omar Carrera, chief executive officer of the Canal Alliance in San Rafael, said that the lack of new housing has led to overcrowding, which has in turn fueled coronavirus infections. Between 1990 and 2013, the neighborhood’s Latino population jumped from about 7,500 to 12,000, while just 300 new units of housing were added, he said.

Carrera’s group has advocated for affordable housing to be built on a lot adjacent to the Home Depot, but the idea has not gained traction.

“Every time we start talking about housing they use the environmental argument to stop the development,” Carrera said. “It makes me wonder if it’s an elegant way to be to maintain the current segregation and the overcrowding, which is a result of the lack of housing opportunity.”

Canal residents are an important part of Marin’s economy, working in construction, retail, landscaping, housecleaning, restaurants and health care, he added.

Matt Lewis, spokesman for California YIMBY, said the lack of housing development in Marin County also has an adverse impact on regional air quality and efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Every day the county imports over 60% of its workforce — some 70,000 workers — from Sonoma, Napa, San Francisco, Contra Costa, Alameda and Solano counties. Between 2010 and 2016, the county added 17,000 jobs but only 700 housing units, according to the Marin Environmental Housing Collaborative.

“Marin is the poster child for this — not only for segregation, but also the poster child for increasing air pollution in other counties because of its lack of housing,” Lewis said.

Marin affordable housing advocates say they have reason for optimism. Projects have recently been approved in Marin City and San Rafael, and Sausalito is looking at allowing some affordable housing on a few parcels in the waterfront Marinship area.

In Fairfax, the developer Resources for Community Development recently opened Victory Village, the first affordable development built in Marin in several years. That project, 54 units of senior housing on Sir Francis Drake Boulevard, was delayed for about 18 months by a group of opponents who appealed the rezoning.

Marin Housing Authority received 761 applications for units at Victory Village — about 14 for every apartment available. About 40% of applicants who landed units are people of color, and 20% are formerly homeless. Dan Sawislak, executive director of Resources for Community Development, said despite a small group of vocal opponents, the majority of Fairfax residents supported the project, which received $3 million from the Marin Community Foundation.

“It was the only affordable project in the county for quite a while, and we got some great support,” he said. “Everybody was pretty heroic to get the deal across the line. It wasn’t easy.”

In Point Reyes Station, there is community support for 36 affordable family units to be built at a former U.S. Coast Guard barracks, said Kim Thompson, director of community engagement for the Community Land Trust of West Marin, which was selected to build the project along with Eden Housing. The project has yet to be approved.

Thompson said that West Marin has been losing essential workers for years because of high land and housing costs, as well as the increasing number of units converted to vacation rentals.

“The displacement is more hidden because it’s a rural area — most people just see all those green hills and cows,” she said. “But hundreds of people have come through our doors in tears because they have been displaced.”

The Point Reyes Station project would help Marin County meet obligations required under a voluntary compliance agreement with the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development. The agreement mandates that at least 100 units of affordable family housing be added by the end of 2022 “outside of areas that are characterized by concentrated poverty,” said Leelee Thomas, planning manager of the Marin County Community Development Agency.

“Development in Marin is challenging for most developers,” Thomas said. “I am hopeful the pandemic has made people realize how vulnerable our renters are to market forces and highlight the need for stabilized affordable housing.”

J.K. Dineen is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: jdineen@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @sfjkdineen