Red flags raised on juvenile hall costs

$500,000 yearly per youth cited in some counties

By Jill Tucker

The cost to run California’s juvenile halls continues to skyrocket, pushing past $500,000 per youth annually in some counties, including Alameda, with young people kept in jail-like conditions despite reforms meant to force the system to rehabilitate instead of punish.

That’s according to a statewide report released this week that also found some juvenile halls skirt state law by locking up young people for a year or more despite limits on long-term commitments.

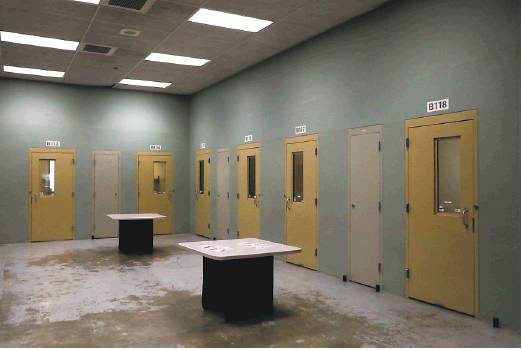

The report, published by the Youth Law Center and the Pacific Juvenile Defender Center, also documented how some young offenders were forced to buy essentials — such as deodorant or soap — with good-behavior points. Instead of the promised supportive homelike environments, many facilities have locked rooms with tiny windows, institutional furniture and barbed wire fences.

The report cites The Chronicle’s reporting on juvenile halls in the 2019 series, “Vanishing Violence,” which led to San Francisco’s decision to shut down its juvenile hall by the end of 2021.

Over the past few decades, juvenile crime has plummeted across California and the rest of the country. Juvenile halls, built or expanded in recent years in response to a youth crime wave in the late 1980s and early 1990s, sit mostly empty, entire wings shut down and dormant.

Fears of COVID-19 outbreaks in detention facilities have pushed populations down even more.

The current conditions and costs raise red flags, the authors said, as California moves to close state youth prisons, transferring the responsibility to rehabilitate serious young offenders to counties after Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation this year outlining the process.

“What we found is that juvenile hall commitment programs suffer from many of the very things that caused Gov. Newsom to want to shutter the state facility system,” said Sue Burrell of the Pacific Juvenile Defender Center. “The governor’s goal of transforming youth justice as we know it cannot be fulfilled by locking youth in jail-like settings where they cannot exercise judgment, develop skills or engage in healthy peer activities, and where they lack meaningful access to their families and the community.”

Across the state in recent years, juvenile halls have increasingly been used for long-term commitments, including youths who have committed probation violations, running counter to state law, which describes them as homelike, short-term holding centers, the authors said.

Tulare County’s commitment program can last up to 730 days, while in Fresno, young offenders locked up to participate in a rehabilitation program generally stay for one year.

State officials, in deciding to close California youth prisons, called on counties to provide programming and support to those who otherwise would have been sent to a state facility, with additional state funding to assist with that.

San Francisco has already decided to close juvenile hall and create community programs, including a secure facility for the most serious offenders.

Officials say the pandemic has slowed the progress in shutting the hall and creating alternatives to incarceration, but they have not extended the deadline for closure. Currently, a dozen youths are in San Francisco’s juvenile hall, which can hold 132 young people.

“The working group is currently focused on housing, and looking at viable small, homelike options for those youth who must be detained,” said Supervisor Hillary Ronen. “I am looking forward to next year when San Francisco will lead the nation in running a truly rehabilitative program for young people that commit crimes.”

The state legislation comes with funding for counties to ensure youth get treatment in community settings and that there are alternatives to confinement, said Meredith Desautels, staff attorney at the Youth Law Center.

“That’s in what the governor signed,” she said. “What our report is trying to say is those words mean nothing if the counties simply revert to the current systems at the county level.”

Probation officials criticized the report and urged state officials to visit juvenile halls.

“This largely opinion-based commentary selects specific and limited facts to support a narrative without giving its audience the benefit of the entire context of our juvenile justice system and the work we do with youth and families,” said Brian Richart, president of Chief Probation Officers of California. “Probation welcomes any interested policymaker to visit any county juvenile facility to learn about the intensive and effective programs and supports provided to each youth so that they may better understand our work, compassion and the successes of our residential care facilities.”

Desautels noted the state legislation does allow counties to place youth in juvenile probation camps as an alternative to the state youth prisons, but many counties, including Contra Costa, Fresno and Butte, have put those camps inside juvenile halls. Typically, camps are in a separate location, with dormlike settings and more freedom of movement.

It’s a loophole that could mean an increase in young offenders locked up in county cells for long periods of time.

“These juvenile hall facilities are extremely expensive to operate and counterproductive to youth and community well-being,” Desautels said. “Community-based alternatives to incarceration have consistently shown better results than confinement at much lower costs.”

Jill Tucker is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: jtucker@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @jilltucker