Golden Gate Bridge barrier offers relief

After seeing model of netting, suicide victims’ families see hope for others

By Rachel Swan

Piece by piece, the net is coming together — a coarse web of steel that will dangle over the side of the Golden Gate Bridge, catching lost and disconsolate souls.

Bridge district officials displayed a 300-foot mock-up Thursday, assembled in a construction yard in Richmond where workers are learning how to tension the cables and fasten the struts before they build the real net in a brutal environment 250 feet above the water. The first parts are going up at night, when work crews shut down a lane of traffic so that cranes can lift large steel parts over the side of the deck.

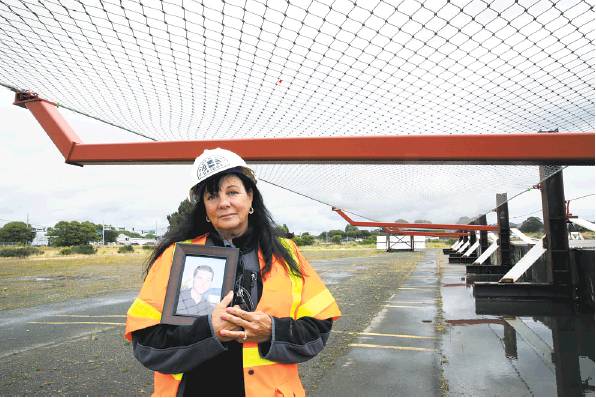

“After all of these years, to see and touch a net — a net that will actually save lives on the Golden Gate Bridge — is very emotional and surreal,” said Kymberlyrenee Gamboa, whose 18-year-old son Kyle jumped to his death almost six years ago.

Gamboa came to the Richmond yard Thursday with her husband, Manuel Jr., and older son, Manuel Gamboa III. The three clutched pictures of Kyle playing basketball as they squinted against a thick, slanting rain. Other families carried portraits of their lost loved ones: 28-year-old Jacob Story, who jumped in 2010; Michael James Bishop, also 28, who leaped off the following year.

Nearly 1,700 people have plunged to their deaths from the orange span, and each story is an endless ricochet of pain. Michael played the violin, took night classes and was about to change jobs — he was under a lot of stress, said his mother Kay James. Jacob had a warm grin and a heart-shaped face. He was diagnosed with depression. When Kyle wasn’t dribbling basketballs or running down a soccer field, he played competitive laser tag.

For each family, seeing the first piece of the suicide net — even a mock-up section — brought a wash of relief.

“I’m just devastated it wasn’t there when we lost our son,” Gamboa Jr. said.

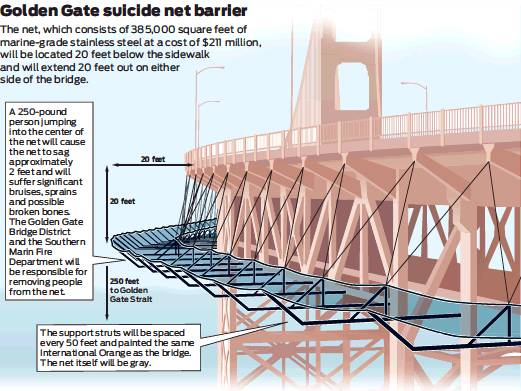

The district’s two contracted construction firms, Shimmick Construction Co. and Danny’s Construction Co., envision an intricate piece of sculpture. Comprising 385,000 square feet of marine-grade stainless steel — the equivalent of seven football fields — it will protrude 20 feet from the public walkway, but remain camouflaged. Its steel cantilever brackets, spaced 50 feet apart, will be painted a rich orange to match the Art Deco structure. Its gray mesh will blend with the fog that shrouds the bridge and the water below.

The Golden Gate Bridge opened in 1937, and quickly saw its first suicide. An average of 31 have occurred each year since 2000, and the number shows no sign of ebbing until the $211 million net is finished in 2021. Last year, the district confirmed 27 deaths, with four more suspected, though no evidence was recovered.

So, people know the bridge for its engineering beauty and dark magnetism: Its towers and suspension cables glisten against the hills of Marin, the preening skyscrapers of San Francisco and the tantalizing sweep of the bay.

Calls for some kind of suicide barrier date to the 1950s, when officials considered stringing barbed wire over the rail. In the 1970s and ’80s, the district studied other concepts, such as railing or fencing with horizontal wires that become slack and harder to climb the higher a person goes.

But it was difficult to build consensus, and plans were hobbled by opposition from preservationists and neighborhood groups. Many critics thought a suicide fence or net would mar the bridge’s aesthetics and obstruct its vistas. Some said that people intent on killing themselves would simply go elsewhere.

Studies from Harvard University and UC Berkeley rebut that argument, showing that nine out of 10 people who are stopped from committing suicide do not kill themselves at a later date. Faith leaders, doctors, and suicide prevention groups like the Bridge Rail Foundation pressed for a deterrent, with support from district General Manager Denis Mulligan.

“Once the net is erected, if someone were to jump into it ... they will probably break a bone or two, but they will live to see another day,” Mulligan said Thursday in the construction yard. Suicide nets are up in nearly two dozen locations throughout the world, he added, and in only one instance has someone climbed out and jumped again.

Yet it took years, and a shift in societal attitudes, for the Golden Gate Bridge, Highway and Transportation District Board of Directors to put a project out to bid in 2014.

And it took the persistence of families like the Gamboas, who became a regular presence at board hearings after Kyle died.

They saw the need for a new form of intervention, beyond the security staff who patrol the bridge’s walkway and monitor its surveillance cameras. Those officers talked 187 people back from the edge last year, but one person slipped through about every two weeks, said bridge patrol Lieutenant Roger Elauria.

Nationally, suicide rates are climbing, but district officials say it’s possible to engineer against tragedy. Once the steel web is up, they hope the deaths will abruptly stop.

Rachel Swan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: rswan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @rachelswan