SPECIAL REPORT | VANISHING VIOLENCE

Juvenile hall costs skyrocket

With many cells empty, counties pressured to spend less — number of detainees plunges as youth crime declines

By Jill Tucker and Joaquin Palomino

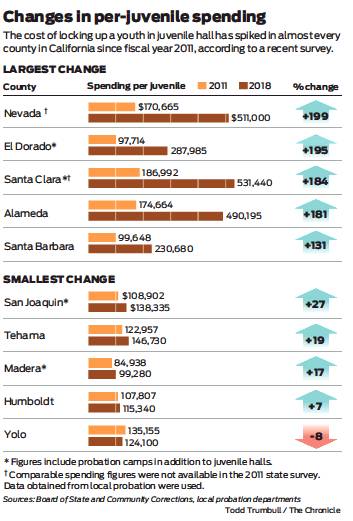

The annual cost of incarcerating a youth in juvenile hall in California has doubled over the past eight years, a new state survey shows, putting pressure on counties to answer for skyrocketing costs even as serious juvenile crime decreases.

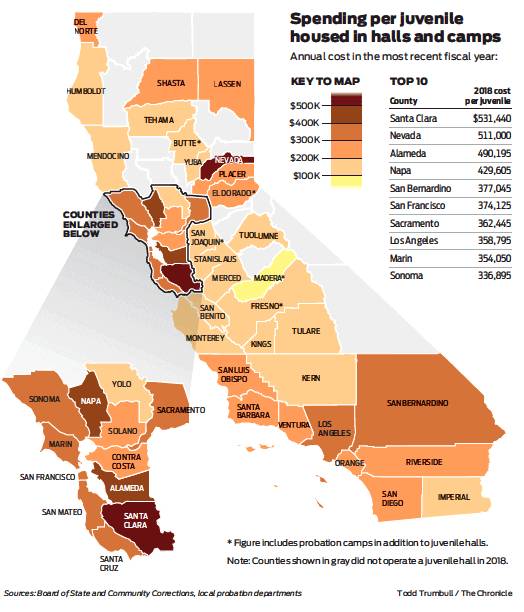

California taxpayers spent an average of $284,700 to keep a child locked up in juvenile hall last year, county-level data from the Board of State and Community Corrections reveal, up from an inflation-adjusted $143,300 in 2011.

Several Bay Area counties were among those spending the most per child, topped by Santa Clara, where the figures showed an annual cost of $531,400 to detain a youth offender in juvenile hall.

The state data bolster the findings of a Chronicle investigation into the dramatic drop in violent juvenile crime over the past two decades in California. The Chronicle found that many counties haven’t significantly reduced spending on juvenile lockups even as they’ve emptied out.

As of December, juvenile halls in virtually every county in California were operating at or below 50% capacity, according to state records.

The survey, obtained by The Chronicle through a public records request, provides the first comprehensive summary of county spending on youth incarceration since 2011, and may be included in the board’s biannual report to the Legislature.

At least 10 counties saw their per-youth spending more than double since 2011. Santa Clara’s costs jumped 184%. Alameda County’s increased 181%, reaching about $490,200 last year.

In El Dorado, the price to detain a young person in the juvenile hall or camp nearly tripled, hitting $288,000 annually, an amount county Chief Probation Officer Brian Richart called “unsustainable.”

In some cases, the state figures revealed even higher spending than earlier data suggested.

San Francisco probation officials, as required, added indirect expenditures, such as administrative and maintenance costs, to the spending amounts provided to the state, pushing the city’s annual price to incarcerate a youth to $374,000 last year — $100,000 more than what The Chronicle had found.

“That’s a huge amount of money to lock someone up, which has been proven to be ineffective for the overwhelming majority of young people,” Michael Harris, senior attorney for juvenile justice at the the National Center for Youth Law in Oakland, said after reviewing the data. “We don’t need juvenile halls of this magnitude.”

The survey, however, offers something of a mixed message for policymakers and the public.

Counties that have aggressively reduced their juvenile hall populations while providing a wealth of services for those in custody typically will have higher annual costs. In contrast, agencies that offer little in the way of services and detain a high number of young people probably have lower per-youth costs.

Differences in local wages, criminal justice policies and accounting methods also make direct comparisons between counties difficult, according to the Board of State and Community Corrections.

Yet the data illustrate a statewide trend of unsustainable increases in spending to incarcerate each child. Some state and local officials suggest reducing bed capacity, repurposing cell units or closing facilities entirely, but they also said state regulations and lack of funding sources could stymie more dramatic overhauls of facilities.

In San Francisco, a majority of the city’s 11 supervisors, prompted by The Chronicle’s reporting, have introduced legislation to shut down the county’s juvenile hall by the end 2021 and create small, community-based alternatives, including a scaled-down secure facility for serious offenders.

The state survey offers more evidence that costs and vacancy rates in juvenile halls must be addressed, county officials said.

“It’s spurring a lot discussion,” said Jessica Selvin, chairwoman of the Alameda County Juvenile Justice Commission. “Maybe at some point juvenile halls are dinosaurs.”

Overbuilt and costs rising

On an average day in December, there were 57 youths in Alameda County’s juvenile hall, leaving 301 beds unused and making it one of the most vacant youth lockups in California.

Alameda Supervisor Richard Valle said the fact that the juvenile hall is at 16% capacity “is a good problem to have” — it means the county is keeping low-level offenders out of locked cells and in community programs.

Yet having far fewer youths in detention hasn’t meant smaller budgets. Spending on the county’s youth facilities was the same last fiscal year as it was in 2011, according to probation data, even though the average daily population dropped threefold over the time-period.

Similar trends have played out across California.

Probation chiefs have attributed the disconnect to labor and other fixed costs that can’t easily be trimmed in huge detention facilities that were built for an anticipated youth crime wave that never came. Services in juvenile halls also were expanded after a 2007 law known as realignment shifted most youths from state-run prisons to county facilities, increasing operating costs.

“California overbuilt juvenile detention space at the county level in the 1990s and after realignment, and now they’re really paying the piper for it,” said David Steinhart, director of the Commonweal Juvenile Justice Program and a key figure in reforming youth incarceration in California. “The question is how do you reverse that? How do you go back on that?”

Policymakers across the state are searching for solutions and paying closer attention to empty, increasingly expensive cells.

In Alameda County, officials are looking to renegotiate labor contracts to address inefficient staffing policies while avoiding layoffs, Valle said. They are also considering alternative uses for the vacant space, including possibly increasing mental health services within juvenile hall.

All of that will take time, Valle said.

“We are going to do our due diligence,” he said. “It may require some major retrofitting in the facility.

In Marin County, Supervisor Damon Connolly said officials are in early discussions about possibly downsizing the 1960s-era juvenile hall to make it more affordable. Last year the county spent $354,000 annually to detain a youth there — more than twice as much as in 2011.

Civil grand jury reports in 2015 and 2018 called those costs “indefensibly high” and recommended that Marin close its juvenile hall and ship youths to a nearby county. Supervisors rejected the suggestion, saying they wanted to keep incarcerated youths close to their families.

Instead, local leaders are considering the benefits of building a smaller juvenile hall that might contain 16 to 24 beds, Connolly said.

“The existing facility is outdated and not cost-effective,” he said. “We need to adapt to the actual numbers we’re seeing.”

El Dorado County is also planning to downsize, building a smaller juvenile hall to replace an existing facility in Placerville and possibly repurposing a second one in South Lake Tahoe.

Both are nearly empty, and the cost to detain a young person in the county has increased 195% since 2011. Cutting the number of beds would save money, but it would also force layoffs.

Chief Probation Officer Richart said he sees the potential to evolve the county’s juvenile justice system, including building a network of smaller, “graduated environments” for young people referred to probation — from respite beds for children with nowhere else to go to secure lockups for serious offenders.

In Santa Clara County last year, the cost of detaining a young person in juvenile hall was the highest in California, at $1,456 per day.

Supervisor Susan Ellenberg said the board has not discussed the topic, and she praised the probation department for providing strong schooling and support services to youths in custody. She suggested per-youth costs are high because the county has been so effective to diverting kids from the locked facility.

Sparky Harlan, longtime youth advocate and CEO at Bill Wilson Center, which provides homeless services for young people in Santa Clara, said that given the dramatic decline in youth incarceration, some of the funds that have historically gone to juvenile hall and probation ranches should be spent on crime prevention programs and re-entry services.

“As your population drops, you should repurpose some of that money to the community,” she said. “But most of the counties in California, including Santa Clara, didn’t redirect much of the funding.”

Drastic action off table

In Napa, taking drastic action to trim costs is off the table for now, despite the $430,000 it currently spends to incarcerate each child, a cost 129% higher than eight years ago.

Like localities in many parts of California, the Wine Country county built a new juvenile hall not long ago. Shutting down the 60-bed facility isn’t being considered, even though it’s less than a third full.

County Probation Chief Mary Butler would like to re-purpose one of the two cell units into a family therapy center or a more homelike setting for youths waiting for placement in group homes or foster care. That could mean replacing cell doors with regular doors and allowing youths to leave to attend a school.

“We’re actually looking at doing something a little more creative,” she said, but added that it’s complicated.

While counties have tapped into hundreds of millions of dollars in state grants to build or expand lockdown facilities over the past decade, there’s been no such funding allocated to convert cells into something else, like a mental health center or a less secure dormitory setting for those waiting for placements in foster homes or other programs.

Other county probation chiefs raised similar questions about how to pay for big changes.

“We would love to do a complete repurposing,” said Santa Barbara Chief Probation Officer Tanja Heitman. “We just don’t have the funding at this point to do that.”

Counties also would have to conform to state regulations regarding staffing and safety for juvenile halls even if the cellblocks are transformed, Heitman said. For example, the law requires a visual check of each youth every 15 minutes and staffing of 1 adult for every 10 juveniles during the day.

“There have to be some changes in the regulations to allow us to have the flexibility to do what we’re talking about,” she said. “Some of the things we would like to do may not completely conform to those regulations.”

While the survey sheds light on county-level costs, it demonstrates that this is a statewide issue — one that’s beginning to gain attention in Sacramento.

The Chief Probation Officers of California association backed legislation last year that would have provided $30 million for county probation departments to repurpose empty juvenile hall space into treatment centers that are more homelike and therapeutic.

In February, the California State Association of Counties created a committee to study how to repurpose juvenile halls. A report is expected to be complete by January, officials said.

And in 2016, the state began a trial program that allowed six counties, including Alameda and Santa Clara, to keep certain nonviolent felons ages 18 to 21 in juvenile hall units. Recent research has found that people in their early 20s are similar to teenagers when it comes to brain development, and might benefit from the services provided by the juvenile justice system. The pilot will run until 2020.

“There are a number of possible approaches to using the empty space in California, but there’s no coherent statewide plan,” Steinhart said.

“Until we come up with better alternatives for what the facilities should look like, the costs are going to keep looking very unsustainable,” he added. “If the trends continue, if the demand for detention goes down and the facilities remain empty, then it’s going to end up looking like a ghost town in there.”

Jill Tucker and Joaquin Palomino are San Francisco Chronicle staff writers. Email: jtucker@sfchronicle.com, jpalomino@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @jilltucker, @joaquinpalomino