Sea level rise meets its potential match

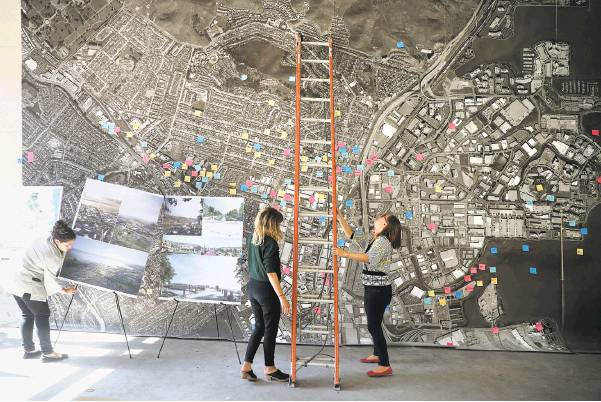

Design solutions on display as tides inch upward into humans’ habitat

JOHN KING Place

The formal events at this week’s Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco are closed to the public, but anyone can visit a related pop-up that occupies a storefront at the foot of Rincon Hill.

That’s where you’ll find 10 detailed visions showing how the likelihood of sea level rise can be seen as not a threat, but a catalyst. The Bay Area, the display demonstrates, can prepare for the future with an eye to a healthier region, where cities and nature overlap in beguiling, sustainable and equitable ways.

At their best, the concepts demonstrate the power of design to stir the imagination. The question now is whether any of them will be powerful enough to leave a mark on the physical landscape — to put down roots, not just dazzle the eye.

“We’re in this transition phase right now,” said Amanda Brown-Stevens, managing director of Resilient by Design Bay Area Challenge, which managed the yearlong competition. “A lot of people invested time and energy over the year, and we want to make sure we’re maximizing the benefit.”

The 10 teams were selected last September from 51 international entrants. Each was assigned to a different site along the bay that could be endangered by rising tides in coming decades. Their responses were unveiled in May.

The teams blended landscape architects with structural engineers, hydrologists with urban designers. The unusual challenge was funded largely by New York’s Rockefeller Foundation. Each team received $250,000 for its efforts.

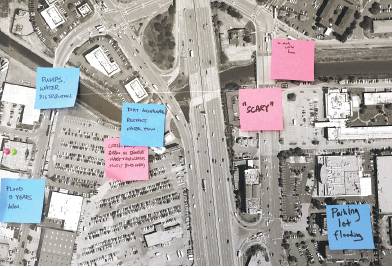

Some concepts blur into others, such as the watery utopias conjured up by separate teams for the shores of Richmond, Alameda and San Rafael. When you consider the scientific projections that daily tides here could climb by 5 feet or more by 2100, there are only so many ways to create higher ground without building stark levees.

But the best of the design visions nudge us to look at the familiar in fresh ways.

One tackles State Route 37 in the North Bay, a roadway from Vallejo to Highway 101 in Novato that slices through an understated mosaic of marshes and former farmland, which stretches between San Pablo Bay and Wine Country. On a quiet day, the drive almost feels as if you’re in the Louisiana bayou — but the daily commute can be arduous, and the low roadway can flood easily.

Various agencies since 2015 have been studying ways to upgrade Route 37, not just to keep cars moving but also to improve the wetlands’ ecological health.

Enter the team Common Ground and its scheme Grand Bayway, which lifts Route 37 a full 25 feet above the earth — and then pulls apart the proposed causeway so that each direction follows its own scenic path. There’d also be a weave of elevated trails and bike paths to offer tantalizing glimpses of what lies below.

“Being up in the air makes all the difference in the world — you start to understand the place and feel the different layers of things,” said Tom Leader, a Berkeley landscape architect who helped organize the team. “Get people’s views shooting off in all directions, not just down the narrow asphalt. Let people spin toward the bay or into the marshes.”

Other Common Ground members included Los Angeles architect Michael Maltzan, who conceived of a 4-mile circular loop above the marshes for bicycles and pedestrians. A 300-foot tower would provide viewing platforms and serve as an orientation point on the flat terrain.

Some flourishes are meant to be provocative: “You shouldn’t take them too literally,” Leader admitted. “But we mean what we’re talking about — this area could be thought of as an ecological Central Park. You could use the (transportation) corridor to help the public get inside.”

Bureaucratic alternatives for Route 37 already include full or partial causeways, but they’re accompanied by images that look heavy and grim. With Grand Bayway, causeways become a way to unlock a portion of the region that most of us barely know.

“Focusing on the design aspect really made people think about the beauty of the area — how it could be appreciated and how design could heighten that appreciation,” said Jessica Davenport of the California State Coastal Conservancy. The conservancy is providing assistance to the official Route 37 studies; Common Ground made a presentation to the working group.

There’s a similar spark in a much different Resilient by Design entry: Unlocking Alameda Creek.

The starting point is one that only a hydrologist could love: The region needs to get more sediment into the bay, so marshes and wetlands in years ahead can grow in pace with the rising tides.

Dull but important, right?

Not the way it’s presented by Public Sediment, the team organized by SCAPE Landscape Architecture of New York.

Unlocking Alameda Creek is a meticulously researched vision for tapping the potential of the waterway that wends from Niles Canyon down through Fremont, Newark and Union City. Passages now channeled in concrete could be freed to allow fine grains of dirt and sand to be carried once again toward the bay. The new banks could be softened with trees and plants, and there could be seasonal trails and parks within them.

The proposal also would dredge mud from upstream reservoirs to restore portions of the South Bay salt ponds in a way that would enhance shorebird protection.

“There are a lot of very realistic elements to it,” said Amy Hutzel, a deputy executive officer at the Coastal Conservancy. “And the images are beautiful, which is helpful.”

Best of all? Unlike some of the Resilient by Design entries, the work from Common Ground and Public Sediment has value in the eyes of government planners.

The Coastal Conservancy has applied for a federal grant to add Public Sediment as a consultant on a portion of the South Bay Salt Ponds restoration effort. Similarly, a $200,000 state grant will be used to integrate members of the Common Ground team into aspects of the Route 37 planning.

What bears fruit won’t look like the more fantastical images. But the infusion of creativity can only benefit the process.

Even in the best of times, long-term environmental concerns must compete with breaking news and short-term pressures. And these aren’t the best of times: We have a president who craves attention as well as power. Many Bay Area residents are more concerned about next month’s rent than high tides someday.

These realities make it all the more important that we plan for the future in such a way that everyday people can see why it’s worth the effort. Design aesthetics aren’t frills. They’re fundamental to showing us what’s at stake.

John King is The San Francisco Chronicle’s urban design critic. Email: jking@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @johnkingsfchron