Outreach over seawall lays foundation for fix

Port of S.F. taps brewery, roaster to inform public about upgrades

By John KingThe ingredients that will be needed to strengthen the seawall that forms San Francisco’s downtown shoreline are as varied as the seasonal espresso of a local roaster and the small holes being drilled into Pier 27.

The latter is a geotechnical test that bores down more than 100 feet to pull up undisturbed samples of the bay mud that lies beneath the century-old pile of concrete-topped rocks that mark where the city stops and the bay begins. The former is a marketing collaboration between Ritual Coffee and the Port of San Francisco to teach people about a defining feature of the city that they might not even know exists.

“We are introducing unseen infrastructure to the community,” said Elaine Forbes, the port’s executive director. “Finding fresh ways to communicate is a big task for us.”

There’s a lot to communicate.

The testing — and for Ritual consumers, the tasting —comes as the city sets out on what could be a decades-long endeavor to improve the seawall’s ability to resist everything from major earthquakes to sea level rise.

The most obvious step right now is Proposition A on the November ballot, a $425 million bond that would provide the initial chunk of funding for an effort expected to cost at least $2 billion. If approved, the bond would pay for the engineering, design and construction of the first round of improvements to the 3-mile-long structure, now topped in part by the Embarcadero promenade.

The seawall was built in 21 sections from 1878 to 1916, adding several hundred acres of seemingly solid ground to the city. But a 2016 engineering study indicated that a major earthquake on the Hayward or San Andreas faults could cause the seawall to slump toward the bay, undermining the streets, buildings and utility lines behind it.

There’s a different form of threat long term: Scientific projections indicate that by 2100 the bay’s daily tides could climb 5 or more feet because of climate change — an increase that would lead to frequent flooding and could, for instance, send streams of water spilling down into the BART tunnel through Embarcadero Station.

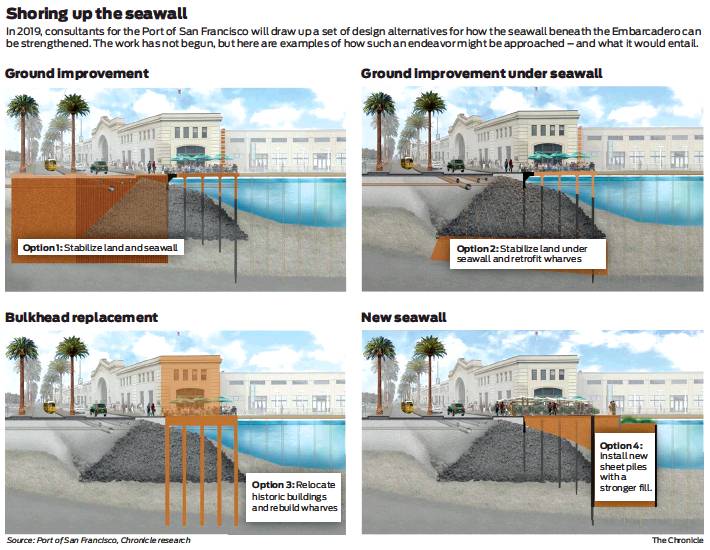

The complexity of these dangers is why the port and the city already have committed $40 million to a 10-year contract with a team of 21 consultants that will conduct a thorough risk assessment, then map out preliminary designs for potential upgrades and conduct the required environmental assessments.

“Figuring out what to do, and what to do first, is our highest priority,” Forbes said. “The more information we have, that’s when we can start the problem-solving.”

Common sense suggests the spots most in need of extra fortification are the stretches of seawall directly north and south of the Ferry Building — low points where bay waters already splash onto the Embarcadero during the extra-high winter tides known as king tides. But the emphasis in the initial phase would be on what portions of the seawall are most susceptible to earthquakes.

Hence the current testing, which starts with Pier 27 and will include about 100 boring sites in the next three months. The aim is to gauge the dimensions of the seawall at each location — how deep and how wide — and the thickness or graininess of the bay mud below.

“We want to understand the geology” from one section of the seawall to the next, said Steven Reel, the port’s project manager. “What the seawall is sitting on will make a difference to the seismic assessments.”

The seismic threat is what’s being emphasized between now and November. Prop. A, for instance, will appear on the ballot as the Embarcadero Seawall Earthquake Safety Bond. The notion of safety applies to the resilience of the region as a whole: Ferry service is seen as a vital transportation link in the aftermath of a ruinous temblor, but that won’t be possible if people can’t get to the landings behind the Ferry Building.

When it comes to spreading the word, the port isn’t relying on campaign brochures and neighborhood forums.

The wrapping for Ritual Coffee’s Seawall Stroll, for instance, urges buyers to “Get to Know the Embarcadero Seawall!” and says that it is in “desperate need of some love. Like big-time, all-hands-on-deck kinda love. Caffeinated love!”

There’s also a partnership with Black Hammer Brewing, which offers a Seawall’s Sea Puppy at its taproom near South Park. The sour beer was launched with a happy hour billed as “Meet the Engineer,” where Reel was on hand to chat with potential customers.

The port did not pay for the collaborations.

The city already has caught the attention of another key audience, the Army Corps of Engineers. The federal agency in June awarded the port $500,000 as part of what is expected to be a $3 million “flood risk management” study for San Francisco’s bay waterfront.

More important than the dollar amount: The appropriation is classified as a “new start,” meaning that it could be the beginning of a much larger project. This probably would parallel and often overlap the seawall work.

“We’re still going through the pieces on how all this might come together,” Reel said. “So far, the money goes only for flood risk, but flood risk and seismic risk are inseparable.”

Whatever the studies find, the port has incorporated long-range threats into its planning efforts. The new ferry landing being built just south of the Ferry Building, for instance, includes a plaza set 3 feet above the current Embarcadero.

This aspect of the project reflects what probably will be the future reality. It also suggests that at some point the seawall and the Embarcadero will also need to be raised — which in turn raises questions about the fate of the historic pier structures.

Those topics won’t be the main focus of the initial studies. They also won’t be ignored.

“We know two things,” said Lindy Lowe, the port’s director of resilience programs. “The water is going to get higher, and the projections keep changing.”

John King is The San Francisco Chronicle’s urban design critic. Email: jking@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @johnkingsfchron

“We are introducing unseen infrastructure to the community. Finding fresh ways to communicate is a big task for us.”

Elaine Forbes, executive director of the Port of San Francisco