State beats its climate law goal

Greenhouse gas levels for 2020 reached early

By David R. Baker

In a major win for California’s fight against global warming, the state appears to have hit its first target for cutting greenhouse gases — and it reached the goal early.

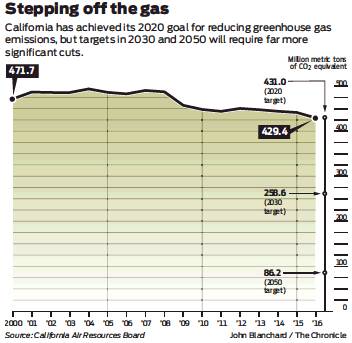

Data released Wednesday by the California Air Resources Board show that the state’s greenhouse gas emissions dropped 2.7 percent in 2016 — the latest year available — to 429.4 million metric tons.

That’s slightly below the 431 million metric tons the state produced in 1990. And California law requires that the state’s emissions, which peaked in 2004, return to 1990 levels by 2020.

Since the peak, emissions have dropped 13 percent. The 2008 financial crisis helped, cutting the number of miles Californians drove and the amount of freight moving through the state’s ports, railways and roads. But emissions have continued falling in recent years even as the state’s economy has expanded.

“California set the toughest emissions targets in the nation, tracked progress and delivered results,” Gov. Jerry Brown tweeted.

Former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2006 signed the law that committed California to curbing emissions and set the 2020 target. On Wednesday, he too cheered the results — and took another jab at politicians elsewhere opposed to climate action.

“Surpassing our 2020 emissions goal ahead of schedule while our economy grows by a nation-leading 4.9 percent and our unemployment rate is at a historic low should send a message to politicians all over the country: you don’t have to reinvent the wheel — just copy us,” Schwarzenegger said in an email. “Business will boom and lives will be saved.”

The emissions drop in large part reflects California’s fast-rising use of renewable power.

Solar electricity generation, both from rooftop arrays and large power plants, grew 33 percent in 2016, according to the air board. Imports of hydroelectric power jumped 39 percent as rains returned to the West following years of drought. Use of natural gas for generating electricity, meanwhile, fell 15 percent.

California is not done. State law also mandates that emissions drop another 40 percent by 2030. While analysts were confident that the state would hit its 2020 target, they are less certain about 2030 — a far tougher target.

“There’s a good chance that we’ll need to take much more aggressive actions to meet those 2030 goals,” said UC Berkeley energy economist Severin Borenstein. “It’s much more challenging.”

Emissions fell by 12 million metric tons between 2015 and 2016. In order to hit the 2030 target, they must fall by about the same amount — at least 12.3 million metric tons — each year.

An executive order by Brown stipulates that emissions must drop still further by 2050, to 80 percent below 1990 levels.

Borenstein pointed to transportation, the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the state, as a major challenge.

According to the Air Resources Board, emissions from transportation grew in 2016, as relatively cheap gasoline and a strengthening economy led to higher fuel sales. And while California has aggressively supported electric cars, only about 200,000 are registered in the state.

“We have not made progress on transportation,” Borenstein said. “We’ve made negative progress.”

In contrast, efforts to slash emissions from power plants have been far more successful, and are running well ahead of schedule.

California regulations require utility companies to ensure that one third of their electricity comes from the sun, the wind and other renewable sources by 2030, a portion that will rise to 50 percent by 2030. Last year, 33.7 percent of Pacific Gas and Electric Co.’s electricity came from renewable sources, while Southern California Edison reached 33.9 percent and San Diego Gas & Electric Co. hit 46.3 percent. So much solar electricity now surges onto the state’s grid at midday that often not all of it can be used.

The annual greenhouse gas inventory released by the Air Resources Board attempts to tally all emissions tied to the state’s economy, and it has limitations.

It does not count emissions from wildfires, which can be substantial. By some estimates, a single massive fire can pump more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than all the state’s global warming programs — including its cap-and-trade system and its effort to promote alternative fuels — manage to cut in an entire year.

In addition, the inventory for 2016 may undercount emissions of methane, a far more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide. A recent study by the Environmental Defense Fund estimated that nationwide methane emissions from the oil and gas industry, largely from leaking equipment, may be almost 60 percent higher than federal government estimates.

The same problem may be present in the state data for 2016, said Tim O’Connor, who heads California energy policy for the Environmental Defense Fund. But the state’s ability to track and minimize methane leaks should improve. A new Air Resources Board rule that went into effect this year will require oil and gas companies to inspect their equipment for leaks each quarter.

“That means if something broke down, it’s going to get fixed,” O’Connor said.

President Trump’s administration has moved to scale back or suspend national climate programs, and he has announced his intention to pull the United States out of the international Paris climate agreement negotiated in 2015. But so far, that has had little impact on California, which has embedded its climate goals and policies in state law.

Chris Busch, research director for the Energy Innovation consulting firm, does not expect the federal government’s current hostility to climate action to hamper California’s ability to reach its 2030 emissions goals. He considers them achievable, in part because the Air Resources Board is working hard to wrest emissions cuts from transportation.

“I don’t see very many ways where we’re going to be significantly held back,” Busch said. “I think we’re in a good position to keep leading on this.”

Fran Pavley, a former member of both the California Assembly and Senate, wrote the climate law that Schwarzenegger signed in 2006, AB32. She, too, says California will hit its next target, because companies working on large-scale energy storage and other technologies capable of fighting global warming have enough time to bring solutions to market — and drive down the cost.

“If you’re thoughtful enough to give the private sector and the innovators enough time to meet the targets, it’s actually quite remarkable what they can do,” she said.

David R. Baker is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: dbaker@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @DavidBakerSF