State on slightly safer footing with wildfire season at hand

By Kurtis Alexander

When Anne Faught got a knock on her front gate recently, she was surprised to find two uniformed men at her rural Marin County property, one with a clipboard.

The firefighters had come to her home for an impromptu safety inspection. They were making sure she had cleared hazards like flammable brush and overgrown trees, both common in the small town of Woodacre, where houses like Faught’s nestle against a landscape of picturesque but perilous fire-prone hills.

“I just did $3,000 worth of tree work,” Faught said, pointing to two compost bins stuffed with leaves and branches. “We all saw what happened last year.”

In the wake of the most destructive fire season in California history, peaking with the fast-burning Wine Country blazes that killed 41 people and wiped out nearly 9,000 homes and other buildings, pressure to reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfire has been immense. And in many ways, the response has been proportionate.

The state stands on at least slightly safer footing this year as a new and perhaps equally challenging fire season approaches.

More firefighting power is in place as California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection crews are repositioned to hazard areas and equipped with new suppression gear, including a fleet of civilian Black Hawk helicopters.

Large-scale tree removal and prescribed burns are in the works with new funding from state and federal coffers.

PG&E is expected to face new sanctions, including the possibility of having to de-energize power lines on windy days, after the utility’s electrical equipment was blamed for sparking several of last year’s blazes.

And fire warning systems are better. State emergency officials are making sure more people will be alerted by phone of an approaching wildfire, having learned from Sonoma County’s failure to send out Amber Alert-style messages as October’s Wine Country fires bore down. Weeks after the disaster, when fires broke out in Southern California, notification to residents there already was improved.

But as significant, and plentiful, as the new fire-protection measures are, they merely nip at the edge of an underlying issue: that fire is a constant in California, and as long as people choose to live in and around the state’s wild-lands, experts say, the threat remains.

“I would not be surprised if we have another big fire,” said Bill Stewart, forestry specialist at UC Berkeley. “I just don’t think we’re where we need to be.”

Short of keeping people from living in high-risk areas, which is hardly possible as Californians seek the space and serenity of life outside cities, experts say the most effective strategy for minimizing danger is hardening vulnerable communities to wildfire — much like what Marin County is trying to do, with firefighters going door to door to make sure every property is prepared to withstand the inevitable.

It’s not an easy task, especially in the Bay Area. Unlike national forests in the High Sierra, where government agencies can reduce the severity of potential fire by logging or burning large tracts of unpopulated land, coastal areas consist mostly of smaller, inhabited parcels. That puts the onus for maintaining safe surroundings on untold numbers of private landowners.

Not only are property owners often lax in securing their lots, experts say, but there’s too little regulation and enforcement of sound land use, namely where houses should be built, what they can be made of and how much vegetation must be cleared around them.

The Wine Country firestorm underscored these problems. The deadliest of the blazes, the Tubbs Fire that devastated Santa Rosa, blasted through well-known hazard spots, some of which had burned before. Still, homes were developed there, often lacking modern fire-resistant materials and without adequate fuel breaks.

“We really haven’t put together the pieces of a resilient fire strategy in local areas,” Stewart said.

A handful of policies have been drafted, although not yet put into law, in the aftermath of last year’s devastation to improve how lands susceptible to fire are managed. But none will completely eliminate the danger.

At least two bills in the Legislature seek to discourage homes from being built in fire-prone forests and grasslands. Both propose giving the state Board of Forestry and Fire Protection more say on the general plans of cities and towns. These plans, which are done periodically, guide where new houses and subdivisions take shape.

The legislation, though, doesn’t necessarily require the communities to do what the state fire experts recommend, whether it’s refraining from developing in a wooded area or requiring more protective open space around homes.

One of the bills, by Assemblywoman Laura Friedman, D-Glendale (Los Angeles County), calls for updating statewide standards for firesafe building materials required of houses in high-risk areas, items like ignition-resistant roofs and tempered-glass windows. Already, the state is planning to add staff to work with cities and counties to enforce these building codes.

But like the provisions on where homes can be built, requirements on what homes should be made of apply only to new housing, meaning most structures wouldn’t be covered by the regulation.

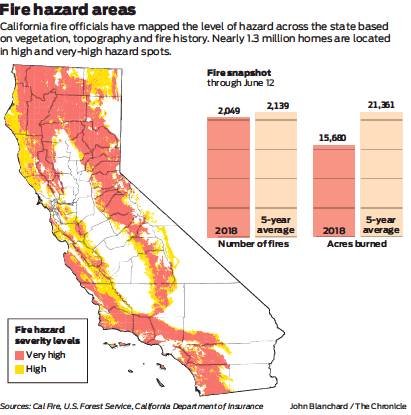

According to the state Department of Insurance, about 3.6 million homes in California, more than a quarter of the total, stand within or near fire-prone areas. Nearly 1.3 million are located in high-risk spots.

A recent executive order by Gov. Jerry Brown on fire safety reaches out to those living in hazardous wild-lands. It seeks to streamline permits for landowners who want to reduce fire danger by clearing trees and brush, and calls for the state to provide assistance with such projects.

Tens of millions of dollars in the state budget for next fiscal year and in California’s cap-and-trade program, which generates revenue by charging businesses for polluting, are earmarked for vegetation management. Also, the finances of the U.S. Forest Service are being restructured to enable more thinning and burning. Most of the new state and federal money, though, is likely to go toward big swaths of public land.

“Resources are an issue,” said Stephen Gort, executive director of the California Fire Safe Council, which focuses on community-level vegetation projects, often on private parcels. “There just may not be enough chain saws available in the state to make a difference.”

Gort’s neighborhood north of Napa organized years ago, and came up with the money, to create a 3-mile fuel break around homes. All of the properties there survived the October fires.

Additional legislation in Sacramento seeks to fireproof the state’s energy infrastructure. Bills introduced by Sen. Bill Dodd, D-Napa, would require utilities to upgrade equipment so it’s less likely to spark and to de-energize transmission lines when fire danger is high.

Already, PG&E has taken voluntary steps to improve safety, such as establishing a wildfire operations center in San Francisco, along with a network of weather stations, to better anticipate risk.

Whatever changes are made to safeguard California’s wildlands this year, they’re likely to come up against another difficult fire season.

The National Inter-agency Fire Center is expecting above-average fire potential for much of California through fall. Late-season rains this spring have spawned a bounty of combustible brush and grass, and the summer is expected to be hot and dry, according to the federal forecast. The fire threat is greatest in the East Bay and Sierra foothills, as well as along the Southern California coast, the report shows.

“We’re already seeing brushfires and the size of the fires increasing,” said Steve Leach, a meteorologist with the Bureau of Land Management in Redding. “I wish I could put out a below-normal (forecast), but we just don’t have a situation like that.”

Christie Neill, a battalion chief for the Marin County Fire Department, said landowners seem to be bracing themselves for the elevated risk, at least in the North Bay.

“I think people are just really more alert this year,” Neill said. “The fires (last year) were so close to us. People were either impacted or they had friends who were impacted. Hopefully, they’ll work with us to take action.”

That appeared to be the case in Woodacre.

After firefighter Cole Rippe finished his inspection of Faught’s property, he advised her to sweep some leaves off the roof and remove brush around a propane tank. Otherwise he applauded her for the amount of vegetation she had cleared.

“It needed to be done,” Faught said as she looked out at some pruned bushes. “I’d been meaning to do it for a long time. But after what happened in Sonoma (County), I knew it had to happen now.”

Kurtis Alexander is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: kalexander@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @kurtisalexander