OPEN FORUM On Water

Plan would restore the Tuolumne

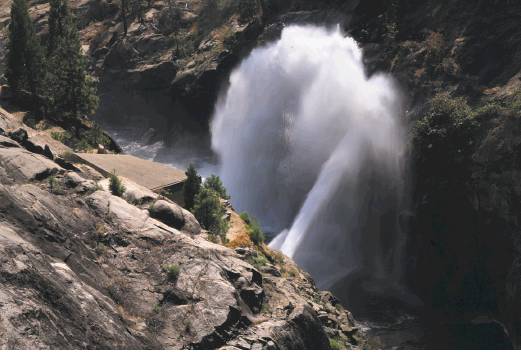

By Peter DrekmeierTo improve the quality of our water and the health of our rivers and the San Francisco Bay-Delta, the State Water Resources Control Board is updating the Bay Delta Water Quality Control Plan as required by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The board is considering requiring higher in-stream flows between February and June, which are critical months for baby salmon growth and migration. For the Tuolumne River, this would increase flows from an anemic 21 percent to a modest 40 percent of unimpaired flow.

During the recent drought, Bay Area residents and businesses stepped up to the challenge of conserving water and dramatically reduced their water use. In the Hetch Hetchy Water and Power System service area, water use declined by 30 percent between 2006 and 2016. But the Tuolumne River, which fills Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, rarely saw any of the water we saved, and it shows. The river is much lower and warmer than it should be, and salmon populations are barely surviving. Where well more than 100,000 salmon used to spawn, the salmon population has plummeted to the low thousands or even hundreds.

Some 2.7 million people in San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara and Alameda counties get most of their water from the Hetch Hetchy Water and Power System, which is managed by the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission. The commission opposes the state board’s proposal to keep more water flowing in the Tuolumne River for three reasons:

Its policy and practice focus on human consumption, not environment or water quality. A 1995 agreement with the Modesto and Turlock irrigation districts — the senior water rights holders on the Tuolumne — that committed the commission to support the districts’ political position on in-stream flow requirements for fish and wildlife, regardless of what the best available science tells us. Irrigation districts are notorious for opposing environmental safeguards, yet the commission gave up its right to think and act in accordance with the environmental values of its constituents.

It wants to maximize stored water in case of drought. This policy of hoarding compromises the future of salmon and the entire ecosystem they support. While it has been demonstrated that the commission could manage a repeat of the drought years even with the revised Bay Delta Plan in effect, it is planning for an extreme scenario that arbitrarily combines the two worst droughts from the latter part of the last century. In a worst-case scenario, the agency could purchase water from an agricultural water district for less than it currently charges its customers.

The Bay Area is projected to grow in the coming years. Plan Bay Area, a road map for growth prepared by Bay Area Metro, forecasts the addition of 1.3 million jobs between 2010 and 2040, attracting 2 million more people to the region. Between 2010 and 2015, half of those jobs were already added, far outpacing the creation of new housing. As a result, the housing crisis and traffic gridlock have worsened, while our environment continues to suffer.

During the recent drought, the Public Utilities Commission released only as much water from its dams as was required by a 20-year-old flow schedule. The rest was impounded for future use. At the height of the drought, the agency had enough water in storage to last three years.

Then came 2017 — the second-wettest year on record — and the dam operators on the Tuolumne had to dump massive amounts of water to prevent future flooding. The river flowed at capacity from early January through May, and stream flows remained high throughout the summer. Had more water been released into the river during the drought, fish and wildlife would have benefited, and the agency still would have had enough water to refill all of its reservoirs twice over.

Without safeguards in place to require more water to flow down our rivers, there’s no assurance the water we conserve will benefit aquatic ecosystems. The Bay Delta Water Quality Control Plan is our best hope to restore a balance between human needs and those of the natural environment that makes our region so special.

Peter Drekmeier is policy director for the Tuolumne River Trust.