Reports detail painstaking examination of destruction

By Kimberly VeklerovThe key to investigating the October 2017 fire siege that burned a combined area more than eight times the size of San Francisco came down to a handful of locations, each just a couple of square feet.

The weeks-long probes into what caused a dozen wind-whipped wildfires, and where they originated, began soon after the fires sparked, as thousands of firefighters from across the state and beyond were still working to douse the flames. While scores of firefighting units fanned out to the edges of more than 170 separate blazes, a small contingent went straight to where they thought the destruction ignited.

Newly released investigative reports from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection detail the painstaking inquiry conducted by a group of fire captains, arson investigators and tree experts who used everything from laser beam technology and cell phone pictures to old-fashioned pattern analysis and tape measures.

They were charged with answering a few basic questions: What happened? Where and how did the fires begin? And were any laws broken?

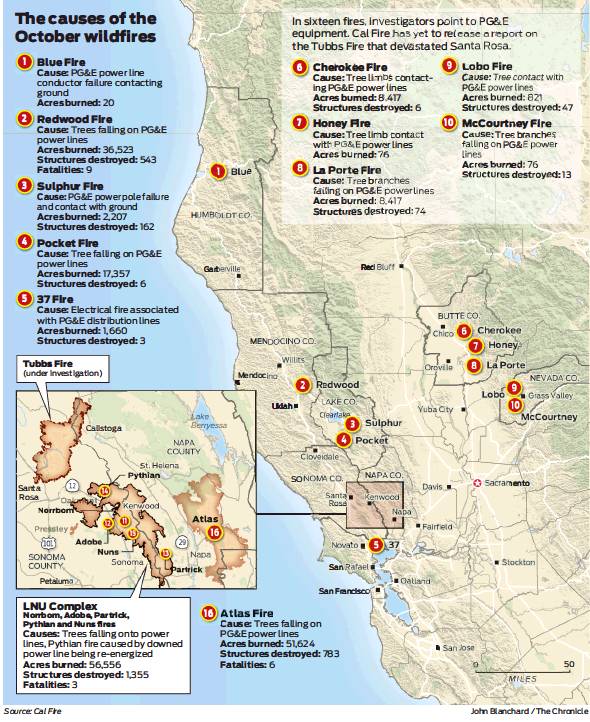

Cal Fire has completed reports on 16 fires to date. The agency released reports into five of the Northern California fires for which no criminal referrals have been made. Eleven other reports have been given to county and state prosecutors for review.

But even where Cal Fire said no violations occurred, the agency determined the fires ignited when electrical lines were disturbed, often by trees falling onto power lines. The findings, in addition to the open question of criminal prosecution, have exposed Pacific Gas and Electric Co. to potentially billions of dollars in damages.

Stephen Pyne, a fire historian at Arizona State University, said fire risk has too often been an afterthought for communities building their power grids.

“You’ve got hot, dry winds — exactly what you need to drive large, high-intensity fires — and that same set of winds is what interacts with power lines to set the fires,” he said. “You’ve got a structural problem — how you’ve built the way you live on the landscape. The power companies may be liable ... but this is a systemic problem and it’s an infrastructure problem.”

For each of the Northern California fires, investigators used burn indicators — visual cues such as ash deposits, the angle of char and stains — to first identify a general origin area, then a specific origin area and ultimately an ignition spot. They brought in round-the-clock security to ensure nothing in the evidence zone was disturbed and kept logs for every action taken.

The lead investigator on the Nuns Fire, which killed two people and burned more than 1,500 buildings and 56,000 acres in Napa and Sonoma counties, described using a color-coded tagging system for a tree top that had crashed into a power line, before a driver transported it to a secure Cal Fire facility.

“I followed (the vehicle) to the evidence storage in my state-issued pickup truck,” the investigator, whose name was redacted, wrote in the report. “I never lost sight of (the vehicle) during the transportation of evidence.”

The handling of suspect vegetation wasn’t the only example of the investigators’ attention to detail.

Investigators such as Cal Fire Capt. Eric Bettger, who probed the Redwood Fire in Mendocino County that killed nine people and destroyed more than 500 structures over 37,000 acres, conducted an exclusion analysis to rule out every possible fire cause except power line disturbances. He wrote at length about why he ruled out such causes as lightning, children playing with fire, fireworks, matches, cigarettes, glass refraction, campfires, debris burning, vehicles and more.

At each origin scene, the investigators walked counterclockwise, then clockwise, documenting key pieces of evidence with different colored flags as they took hundreds of pictures. They ran magnets over ignition areas to check for metal fragments and other particles.

Other experts inspected tree parts and found that none had rot, defects, disease or pest infestation. The high winds appeared to be the cause of them falling.

Doug Wood, a San Francisco attorney who has litigated numerous arson cases and written about fire cause analysis, said the Cal Fire reports will be “absolutely foundational evidence” in any civil or criminal case.

“The process of fire investigation has moved from a lot of art and relatively little science to a lot of science and a bit less art,” Wood said.

Nowadays, fire investigators use a standardized guide established by the National Fire Protection Association that’s based on the scientific method, and involves testing and ruling out hypotheses, he said. The investigators are tasked with figuring out the primary ignition source and the first ignited fuel, and why those two things came together.

“Once you figure out the origin correctly and you’ve got a hypothesis, you do your best to disprove it and see if it can withstand all attacks you throw at it,” Wood said. “Fire investigators are not case makers. They’re puzzle solvers.”

Kimberly Veklerov is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: kveklerov@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @kveklerov