Napa Valley split over land’s future

Vineyard curb sought to preserve trees, streams

ESTHER MOBLEY

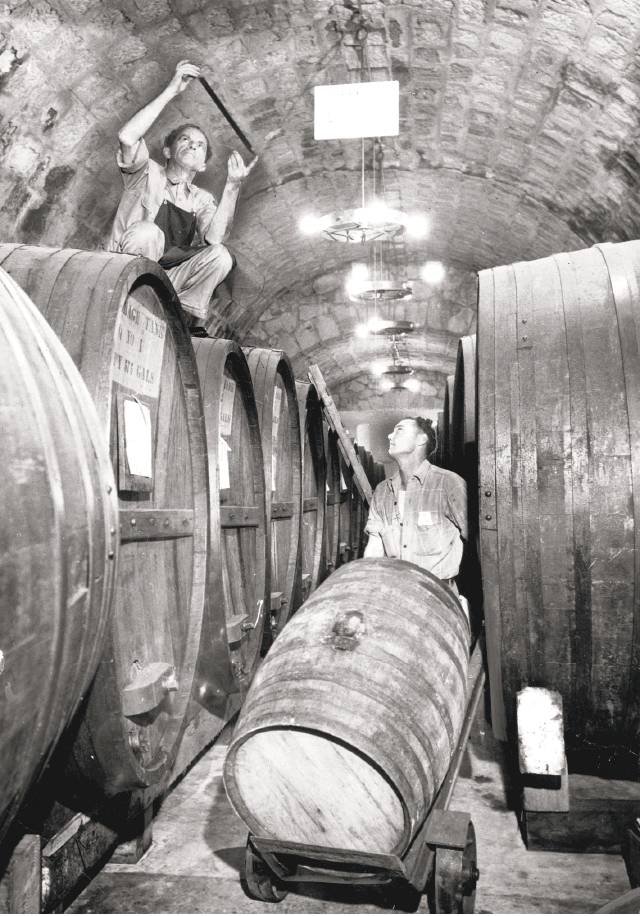

Fifty years ago Monday, Napa County passed an ordinance that has defined the course of its history and, one could argue, determined the history of California wine.

The Napa Valley Agricultural Preserve, passed by the Board of Supervisors on April 9, 1968, resolved to protect the valley’s most precious resource: land.

Here, land holds an extraordinary potential for producing fine wine grapes, and Napa residents wanted to protect it from strip malls and subdivisions. Agriculture, which in Napa means viticulture, was declared the “highest and best use” of this unique, unmatched slice of earth.

Now, a half century later, Napa has arrived at another turning point, this time with a June ballot initiative that could alter the course of its history again.

Measure C, the Watershed and Oak Woodland Protection Initiative, on a mail-in ballot to be tallied June 5, seeks to curb further vineyard development to preserve the streams, oak trees and natural habitats on the Napa Valley hillsides. It’s a proposal that has bitterly divided the valley.

Its supporters, led by local environmentalists Mike Hackett and Jim Wilson, believe that after 50 years of unbridled success, the profit-hungry wine industry has brutally exploited the landscape. In the name of growing grapes, too many trees have been cut down, too much water contaminated. Measure C would mandate that vineyards have larger setbacks from streams and would set a hard limit on further deforestation.

The measure’s opponents, on the other hand, argue that it would undermine the one thing that has kept Napa Valley beautiful and made it prosperous: agriculture.

The harsh tenor of the debate over Measure C, however, has made it clear that much more than trees and streams are at stake. At its core this battle is between dueling visions for what Napa Valley should be — visions of preservation versus development, of stasis versus growth.

“This is the next step for the next 50 years. If the initiative doesn’t pass, we’re lost.”

Mike Hackett, local environmentalist and supporter of Measure C “If this initiative passes, it will be the beginning of the demise of the wine industry in Napa County.”

Dario Sattui, winery owner and opponent of Measure C

“This is the next step for the next 50 years,” Hackett says. “If the initiative doesn’t pass, we’re lost.”

That assessment finds a strange echo in the words of a Measure C opponent, Dario Sattui, owner of V. Sattui and Castello di Amorosa wineries: “If this initiative passes, it will be the beginning of the demise of the wine industry in Napa County.”

If the 1968 Ag Preserve’s objective was to protect Napa Valley for agriculture, the question, it seems now, is: Does Napa need protection from agriculture?

* * *

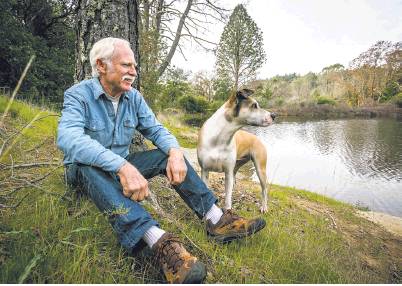

Randy Dunn embodies the case for Measure C and its environmentalist supporters. The winemaker and owner of Dunn Vineyards has lived on Howell Mountain, in the small Napa County town of Angwin, since 1978, making some of the region’s most distinctive and celebrated wines. In recent years, as Howell Mountain has become one of Napa’s most sought-after terroirs and more vineyards have been planted, Dunn has become the mountain’s self-appointed steward.

“We’ve got too much vineyard development already,” says Dunn. “What happens to the fish in the streams when you’re sulfuring the vineyards? And the critters in the woods?” Chemicals used in farming, he points out, trickle into the Howell Mountain tributaries that feed Lake Hennessey, a major source of county drinking water.

In February, Dunn was part of a group of high-profile vintners including Andy Beckstoffer, Robin Lail, Beth Novak Milliken and Warren Winiarski who publicly expressed their support for Measure C in a letter to the Napa Valley Register newspaper. “Enhancing oak woodland protections is not anti-agriculture,” they wrote. “Rather, it is pro-responsible and sustainable agriculture, pro-water security, pro-community, and pro-climate. Our county’s Agricultural Preserve depends on a healthy watershed.”

To these vintners, Measure C’s provisions are modest: New vineyards must be kept at least 25 feet away from streams, and only 795 acres of oak trees in land zoned as agricultural watershed may be removed in order to plant vineyards. After the 795-acre limit is reached, permits will be required to cut down any more oaks.

Hackett contends that 5,000 new acres of grapevines could be developed before the tree-cutting limit is reached, an amount the county Planning Commission estimates will take until 2030 to plant.

Dunn is so passionate about the preservation of his hillside that in 2006, he donated $5 million and helped raise $20 million more to acquire Wild-lake, a 3,000-acre property on Howell Mountain. The property was then donated to the Land Trust of Napa County, ensuring that it will never be developed. Wildlake remains pastoral and, Dunn emphasizes, helps protect Bell Canyon Creek, which provides drinking water to the city of St. Helena.

It’s because of Dunn’s investment in Wildlake that one proposed vineyard development bothers him in particular. Adjacent to Wildlake is a 40-acre parcel purchased six years ago by Mike Davis, a former technology entrepreneur who owns Davis Estates, a winery in Calistoga. Davis wants to plant a vineyard there. He’s submitted a permit application to put in 10 acres of vines, which would require cutting down some oak trees.

After all that Dunn has done to keep Wildlake wild, the idea of any deforestation right next door is hard to swallow.

“It’s a one-way street,” Dunn says — once open land has been developed, it can never be regained. “That’s why we can’t just sit back and do nothing. This is about setting an example for the rest of the world.”

For Dunn and those in favor, Measure C is about fulfilling the legacy of the Ag Preserve: taking a stand to keep Napa bucolic. No one understands this better than Winiarski, the founder of Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars, who actively campaigned for the Ag Preserve in 1968 and is now campaigning for Measure C.

“It was easier in 1968 to think about agriculture as a favorable alternative to housing development,” Winiarski says. “But agriculture at its current rate is unsustainable, because the resources of this valley are not endlessly exploitable.

“Agriculture is the highest and best use,” he continues, “only if it’s qualified.”

* * *

Many others in the wine industry oppose Measure C just as fervently.

“I get upset knowing that we, as growers and vintners, are being cast as offenders,” says Chuck Wagner, owner of Caymus Vineyards. “We are the essence of why the valley is beautiful, and why it’s been kept and improved over the years.”

All of the major trade organizations, including the county Farm Bureau and the Napa Valley Grapegrowers, are against Measure C, contending that it is “anti-ag.” And to be anti-ag, they say, is to be anti-Napa.

“Already Napa County has some of the strictest environmental regulations in the country, if not the world,” says Farm Bureau policy director Ryan Klobas. The additional regulations proposed by Measure C are excessive, he says. “We’re concerned about the costs to small family farms.”

The Napa Valley Vintners, the county’s winery association, worked with Hackett and Wilson last year to draft Measure C, and initially expressed support. But in January the association issued an official statement against it, explaining that “the majority of input the board received from NVV members conveyed opposition.”

The plan could bring about too many unintended consequences, opponents argue. What about Measure C’s exception for cutting down trees near houses? Does that mean everyone will build mansions on the hillsides instead of vineyards? October’s wildfires, too, have factored heavily in the debate. Didn’t the vineyards serve as firebreaks much more effectively than trees?

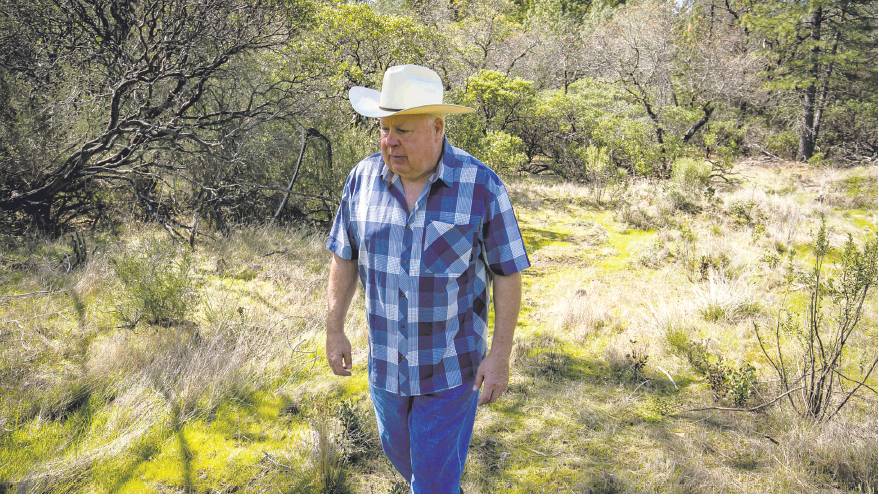

But the core argument in opposition to Measure C, like the argument in favor of it, harks back to the Ag Preserve. “We have two choices: either the way of sustainable agriculture or the way of development,” says Sattui. “Agriculture as defined by the Ag Preserve is the highest and best use of land in Napa County. We’re not going to go back to the way of wild animals.”

Davis, the vintner who hopes to plant next to Wild-lake, emphasizes that his land is zoned for agriculture, just like Dunn’s main property. He’s all for Dunn’s decision to put Wildlake into the Land Trust, but says, “At what point does their preserve stop, and agriculture take effect?

“If the other vintners feel so strongly,” Davis continues, “then why don’t they take out their vineyards and plant trees instead?”

So it goes in Napa Valley these days: “Vote No” and “Vote Yes” signs anchored to front lawns, debates at public forums, letters to the editor.

But what if the fate of Napa Valley has already been sealed, and this ballot initiative has little power to change it?

* * *

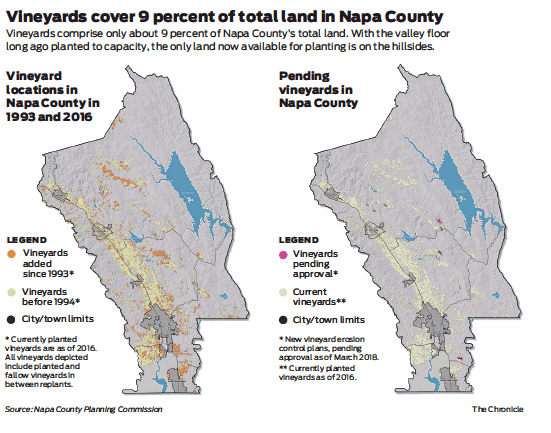

It might surprise the visitor who drives up the Silverado Trail and sees only an endless succession of grapevines, but vineyards make up just 45,000 acres, or about 9 percent, of Napa County’s total land. If the Planning Commission’s projection of 5,000 additional vineyard acres by 2030 proves correct, that would bring the percentage of vineyards to just 10 percent. Parks, open space, rural lands and grazing land make up about 80 percent of the county.

So it’s not as if Napa is running out of land in a literal sense.

And yet it’s nearly impossible to plant a new vineyard here today.

That’s partly because the valley floor was planted to capacity long ago. The only land still available to plant is on the hillsides — essentially, in the agricultural watershed, the area that concerns Measure C. Hillsides, as agricultural enterprises, are unwieldy: harder to access, prone to erosion, studded with trees, crawling with wildlife. Building on a hillside here is already highly regulated.

The true barrier to planting in the hillsides, and to Napa Valley land ownership today, is the substantial cost. When hillside vineyard land is selling for $180 million — as the 1,300-acre Stagecoach Vineyard did, in 2017 — access to the Napa Valley dream is severely limited.

Even if a would-be vintner can afford to buy the land, the time and expenses required to convert it to viticulture, regardless of any potential tree-cutting, make vineyard ownership a longshot even for the wealthy. Davis says that his Howell Mountain property is probably not financially viable: “I don’t think it will turn a profit in 20 years.”

The Napa Valley ideal embodied by his neighbor Dunn, it seems — ambitious young winemaker buys Napa hillside vineyard, makes world-class wines — is already lost.

Buying land is one thing. But who among us will still be drinking Napa wines in the years to come? As land prices and wine prices become locked in a vicious circle, each forcing the other higher and higher, even purchasing wine becomes nonviable for many.

Measure C, and the oak trees it aims to protect, epitomize a battle over what Napa Valley has become and what it should be. It represents the belief that a collective community decision can change the course of Napa’s future, as it did in 1968.

But the question is whether, in 2018, it is still possible to make such a decision. Or has the valley’s fate been sealed?

Esther Mobley is The San Francisco Chronicle’s wine, beer and spirits writer. Email: emobley@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @Esther_mobley