WINE COUNTRY FIRES

Life amid the ashes

Recovery slow, painful, demanding in hardest-hit Sonoma County

By Lizzie Johnson and Kevin Fagan

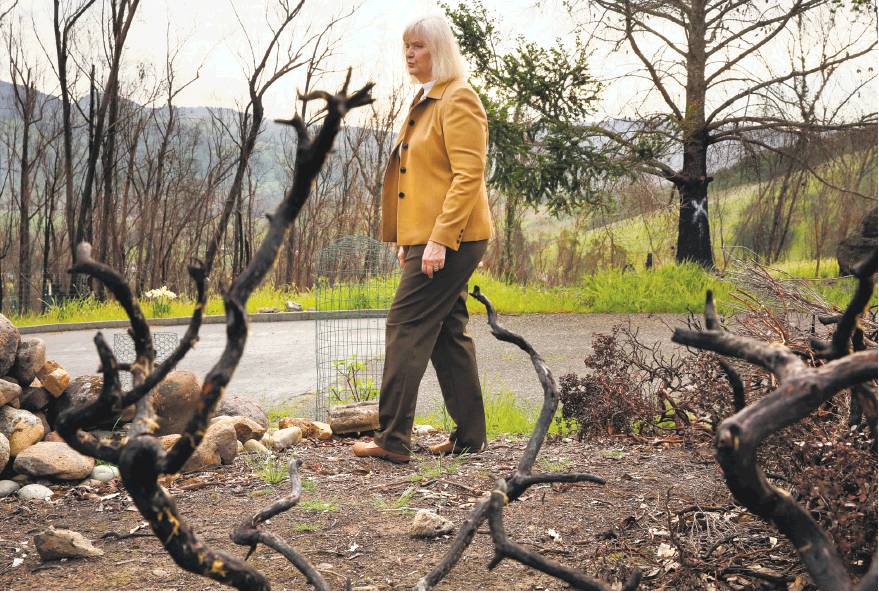

Susan Gorin aches to fast-forward to well past next year — when she once again has a home on what is now an ashy lot.

Peter Alan wants to turn the rubble of his Craftsman art studio into something meaningful. Lisa Mast longs to look out her window and see something across the street besides blackened reminders of the flames that swept through before sunrise Oct. 9.

That was the night, six months ago, when hot Diablo winds blasted across the hills from the east, snatched up some sparks and rained fear and sorrow on the North Bay.

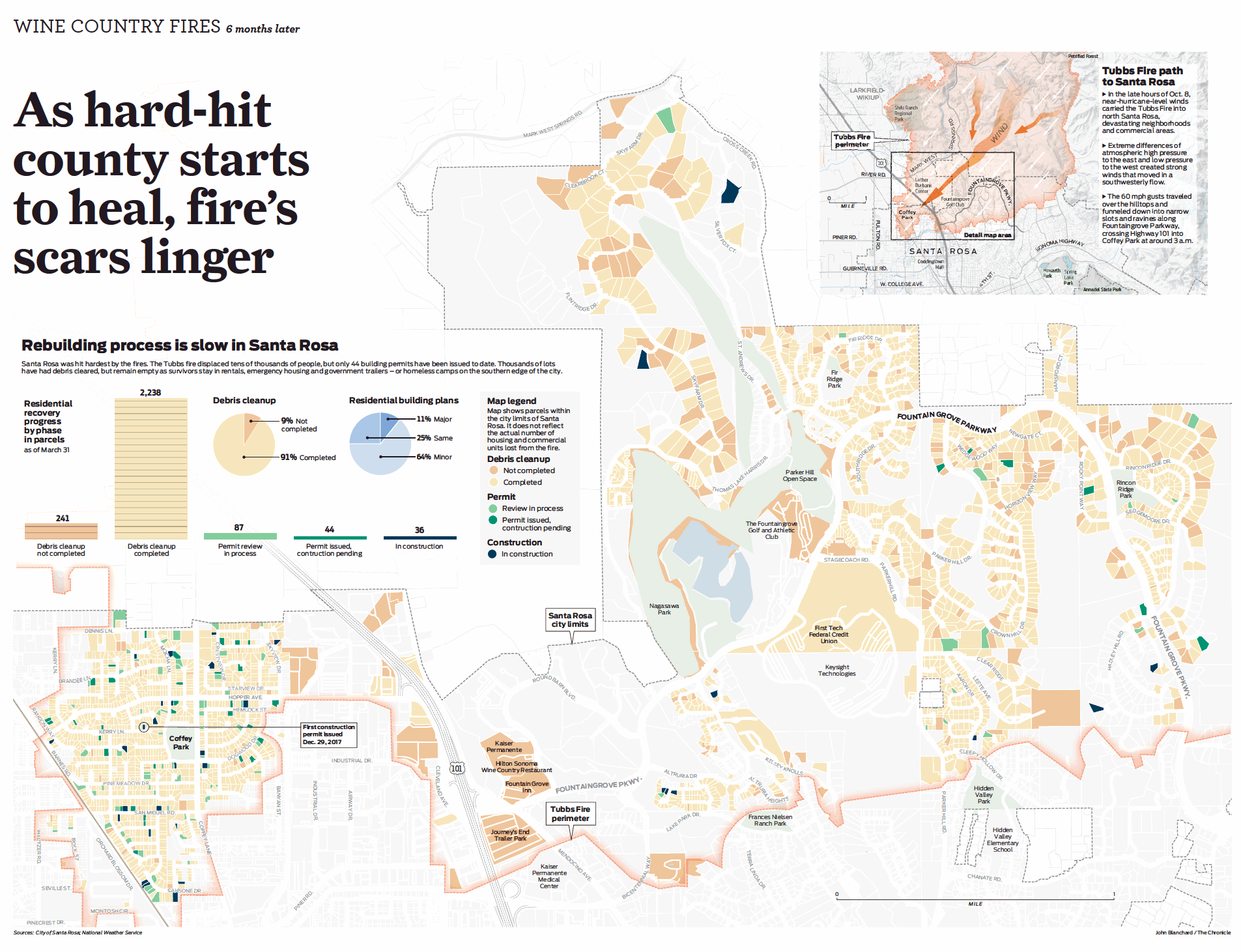

Sonoma County took the brunt of it, and its biggest city, Santa Rosa, suffered most of all. Gorin’s lot and thousands of others are still empty. Tens of thousands of people — the county has not tracked exact numbers — were displaced by the fires, and many of them remain in rentals, emergency housing and government trailers. Homeless camps with hundreds of people mark the southern city limits of Santa Rosa.

Today, Sonoma remains a county under fire.

“I have never experienced a disaster quite like this,” said Gorin, a Sonoma County supervisor. “The seven stages of grief are very much evident here. This will be with us for a long, long time.”

These are the stories of some of those who lost nearly all they once knew. Six months in, they realize — better than they did in October — they may never get it back.

Rebuilding a life

It was in the hills near Calistoga that the worst of October’s blazes sparked: the Tubbs Fire.

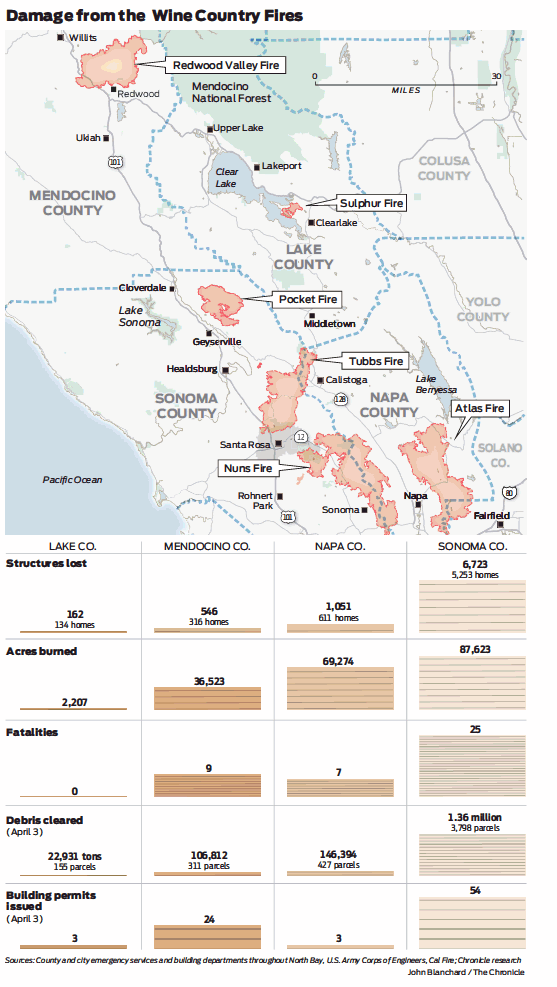

It fed off the air, carrying dinner plate-size embers 12 miles across Sonoma County in four hours. The Tubbs Fire consumed 36,807 acres and destroyed 5,636 houses, businesses and other structures, most of them in Santa Rosa. It was joined by several other blazes throughout the North Bay that, together with the Tubbs, killed 41 people — the highest death toll of any wildfire disaster in the state’s history.

The fires had been burning for three days when Gorin, who was in an emergency Board of Supervisors meeting, received a text message from state Sen. Mike McGuire, D-Healdsburg.

“Is this your house?” it read. He was on a tour of the evacuated Oakmont neighborhood, a newer subdivision of million-dollar houses bordering Trione-Annandel State Park in the hills east of Santa Rosa.

The lawn of Gorin’s three-bedroom home was smoking. McGuire saved Gorin’s car and her husband’s road bike, along with some jewelry, family photos, clothes and computers that he hauled out in pillowcases, before the flames got there.

The house was incinerated. So was Gorin’s former home in the Fountaingrove neighborhood just to the north — an obliteration of 25 years of memories between the two.

“It amazes me how completely a fire can consume a house full of furniture and photos and books and dishes, reducing it to virtually nothing,” Gorin said. “You could see the metal wiring from the house, the hulks of the washing machines and appliances. You could see where the china fell down and shattered. It was a total loss. It destroyed everything.”

Her husband suggested living in an RV on their lot. That’s what others who lost their homes have done. But the refrigerator would have been tiny, and outings to the septic tank station frequent. Gorin didn’t want to do that. “I can’t function in an RV on this lot,” she told him.

So they’re in a rental unit in Oakmont near the home where Gorin’s mother-in-law lives. Insurance pays their rent.

Gorin is lucky, she knows. But the rental is not home. It doesn’t have sweeping views of the state park. There aren’t fruit and oak trees out back. And it’s not as comfortable — not like their old place. The furniture and family heirlooms they moved from Fountaingrove to Oakmont are gone. So are their clothes.

Gorin spends her days slogging through mind-numbing paperwork, applications and meetings with fire victims planning their rebuilds, even as she plans her own. They tell her there is nowhere to live, that this — trying to rebuild a life — is harder than they thought.

She knows how it feels. She has credibility with them; she’s going through the same things.

“I set aside one afternoon where I could go sift through the ashes of my home and use a whisk broom to sweep things away,” she said. “I wanted to sit there and cry over what I lost.”

But she added, “I’m grateful I have the capacity and time and empathy to give. There are so many still struggling.”

Nothing is quick

The wildfires didn’t discriminate. They destroyed a low-income mobile home park near Highway 101. They destroyed senior retirement homes and the mansions that dotted the hills above Santa Rosa. Thousands of rental units — the exact number of apartments and houses is unknown — were wiped out.

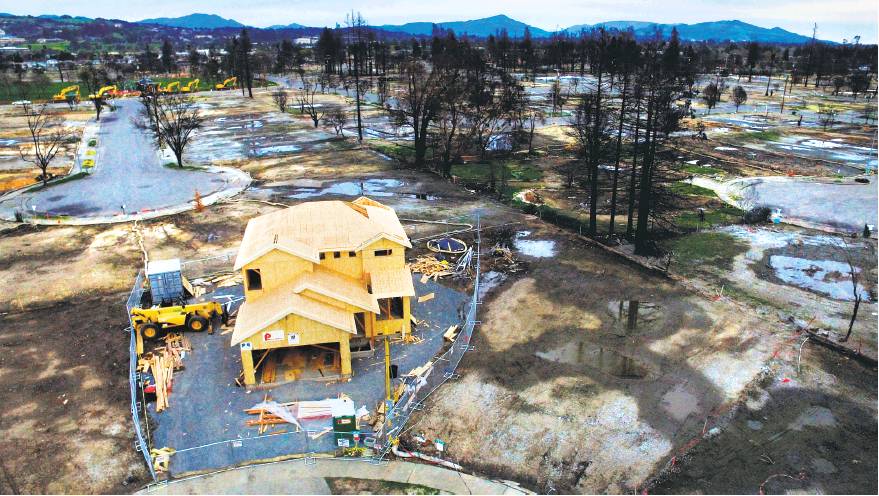

Few residences have risen from the ashes.

Only 54 building permits had been issued in Sonoma County as of March 27 for burned-out lots. Even if they plan to pull a permit, many are agonizing over how to pay for their house reconstruction — more than 40 percent of people who lost homes were underinsured.

Until 2013, Sonoma County was building only 500 new housing units annually. In total, when accounting for job gains and fire losses, it will need an additional 26,000 units by 2020.

The county opened a resilient permit center, a separate department for fire survivors trying to rebuild their homes. Officials lowered fees and cut red tape, promising to issue permits within a week of application, despite criticism that doing so could result in homes being rebuilt in fire-prone areas.

Mark Mitchell, co-owner of Lake County Contractors, has a good guess of what recovery will look like. The 52-year-old has an unusual goal — he strives to rebuild the first home to go up after every major state disaster. He helped erect the first one after the massive Lake County wildfire in 2015. That was shortly after he started his business. Now, he’s finishing the first one in Santa Rosa’s devastated Coffey Park neighborhood. Forty-five clients are on a waiting list for his services.

“It never happens as quickly as people think,” Mitchell said. “By the end of this year, I would imagine less than 10 percent of the total losses will be rebuilt. Next year, it will be bigger. And the year after, when big builders start buying up lots with pre-made designs, it will skyrocket. We saw that in Lake County. It wasn’t until other houses started rising that people saw there was possibility.”

Half the clients he works with give up before anything is built. They aren’t ready for the barrage of choices, and if they’re couples, they can’t always agree: Paint? Tiles? Windows? Floor plan? Carpeting? Cabinetry?

“All of these people are just thrown into it,” Mitchell said. “They don’t have a choice. Most of them don’t want that choice. They liked where they were, and they don’t want the additional stress of building a home on top of losing everything.”

The county has made the process easier. Mitchell is able to submit applications electronically — something many counties don’t do. But there have been holdups. Like when Fire Department officials delayed a home he’s building in Coffey Park. The sewer laterals in the neighborhood weren’t big enough to support the now-required fire sprinklers. It took a few weeks, but they sorted it out.

Everyone is figuring out the best way to build, Mitchell tells clients. When you’re the first, there are bound to be delays. But for some people, being the guinea pig is too overwhelming.

“We’ve had clients come to us and sign design contracts,” he said. “A week later, they will decide they aren’t going to rebuild. It won’t be one size fits all. It’s a stressful process after you’ve already been through enough.” A trailer isn’t home

“It amazes me how completely a fire can consume a house full of furniture and photos and books and dishes, reducing it to virtually nothing. You could see the metal wiring from the house, the hulks of the washing machines and appliances. ... It was a total loss.”

Sonoma County Supervisor Susan Gorin, describing her destroyed home

Many who were renting when the flames came can only wish they were burdened with too many choices. With nowhere to go, and no way to pay for housing, thousands of them — the best estimate officials can come up with — are stuck in limbo lodging.

Within three weeks of the fires’ ignition, the Federal Emergency Management Agency received more than 4,500 unemployment claims. Most of those people had already been living paycheck to paycheck, getting by on cheap rent. Some have moved to the Central Valley or out of state to find affordable housing, saying goodbye to a county where the rental vacancy rate went from just 2 percent before the fires to zero afterward — and the average rent has gone up more than 30 percent.

A few who didn’t leave, couldn’t stay with friends and family or weren’t able to find a rental wound up in temporary housing from FEMA. The biggest colony is at the Sonoma County Fairgrounds RV Park, where all of the 101 brand-new trailers brought in by the agency are filled.

The trailers are part of a disaster-recovery effort that has housed about 400 people in apartments, trailers or modular housing units. People can stay up to 18 months.

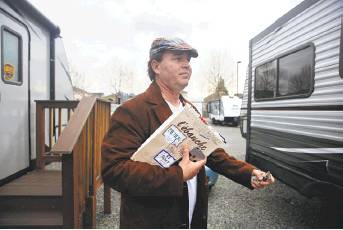

The population at the RV park includes people who were living on the margins of the economy in jobs like housekeeping, where a couple of missed paychecks always meant trouble. Or artists who live commission to commission, like 49-year-old Peter Alan.

After flames gobbled his studio in Glen Ellen southeast of Santa Rosa, he scored the smallest model FEMA trailer, the one with a single bed, kitchenette, bathroom and a fold-down table. Rent and utilities are free while Alan rebuilds his art career working in paint, multimedia and sculpture. He estimates he lost $120,000 in art and $18,000 in supplies in the fire.

“I’m truly grateful to FEMA for this space, but I really do need to get a studio and a place of my own,” he said. “It’s been an adjustment. The energy around the park here can be abrasive, often very noisy, and there’s no place to do my work in a trailer this small.”

Alan, a trained massage therapist, has been taking clients and saving money for rent. But he’s also applying for art grants.

He’s hoping to open a studio with two other local artists and create sculptures and other works from fire debris. For now, Alan is storing ash and gray-black fragments from his destroyed studio — “not from anywhere else, to be respectful” — in his mother’s garage in Santa Rosa.

“I don’t want people to be sad when they see it,” he said. “I want this art to be healing.”

Across the RV park from Alan’s trailer lives Daisy Car-reno, 35. She would be on the street if not for her FEMA rig.

Carreno, her husband and their three children all scrambled out of their rented house in Coffey Park just as the Tubbs Fire consumed it. Her husband went back into the flames to rescue their car. But that was it.

Carreno is a house cleaner and her husband works as a printmaker — but they still can’t afford what they’ve been able to find. Every two-bedroom place costs $2,500 a month or more, and they’d barely been able to cover the $1,700 on the house that burned.

All that remains of their former home is a handful of half-melted bracelets and necklaces and the center ring of John Denver’s “Back Home Again” LP. That all sits on a shelf in the trailer like talismans.

“We are going to frame this when we move into our real home,” Carreno said in Spanish, touching the LP fragment tenderly. “My daughter says it doesn’t matter what the roof is. The home is where the family is.”

From a home to a tent

They are the unluckiest of the survivors.

Isaak Faber has lived in a lot of places during his six years of life — maybe half a dozen as his family followed jobs and circumstances around the area. For most of the past six months, home was a tent pitched in the middle of scores of other tents. He knew it had something to do with that fire he had to run from with his mom and dad in October.

Isaak goes to kindergarten in Santa Rosa on the other side of town from his burned house and watches other kids go back to homes when the school bell rings. One chilly recent day, he nudged a little red toy sports car with his foot down the dirt pathway at the homeless camp in south Santa Rosa. It was what passed for fun for the afternoon. It wasn’t really fun.

“I just want to go home to my real home,” he said, staring at his shoes. Isaak’s father, 38-year-old Keith Faber, hugged him for a long moment.

“Soon, son, soon,” Faber said.

A few days ago, the Fabers found a spot in a shelter. It’s still not home. They’ve got a lot of company in their misery.

Sonoma County has the overwhelming majority of the homeless population of the North Bay, much of it in and around Santa Rosa, but before the fires it had been making progress. The last street count, taken in 2017, found the homeless population down 2.4 percent from the year before, at 2,835 people. The fires ruined that.

The county’s latest annual homeless count, taken in February, hasn’t been released, but those who did the counting are sure it will be up substantially. All 1,200 beds at the county’s homeless shelters are full.

Homeless camps beneath Highway 101 overpasses mushroomed into huge sprawls shortly after the fires. When police cleared them out in November, campers migrated to southern Santa Rosa, where the existing small settlements swelled from about 60 people to more than 250 in tents, cars and RVs. This is where Isaak was living.

“It’s cold, wet and it’s hard being here,” Faber said shortly before moving into the shelter. He stays with Isaak and his three other children while his girlfriend works at a bakery.

“The house we rented in Coffey Park was a great deal and had enough room for my family. And we got it for $500 a month,” Faber said. “But I can’t find anything like that now, and we don’t bring in that much money.”

Jennielynn Holmes, director of shelter and housing for Catholic Charities, the foremost homeless-aid organization in Sonoma County, helped lead an effort this winter and spring to find roofs for Faber and about 110 others now living in the encampments behind a Dollar Tree store. A one-stop navigation center — referrals only, no shelter beds — managed to steer nearly 30 people inside by early April, and to work up individual shelter or housing plans for another 45. But hundreds, and possibly thousands, of homeless people displaced by the fires remain in streets and fields throughout the North Bay.

“A lot of us never thought it would be a fire that would cause this much damage, throw so many people outside,” Holmes said. “I always thought it would be an earthquake. It’s just been heartbreaking. We had a housing crisis on Oct. 7 (the day before the fires). And now it’s worse.

“It’s going to be a three- to five-year recovery period for the most vulnerable people.” Stress can overwhelm

The temporary digs with no certain future, the aggravation of learning how to rebuild a house, the nightmares of flames — they’re all things people have to adjust to. It’s not going easily.

For Karen Erickson, the past six months have been a slow spiral. She lost her Fountain-grove home. She lost her neighbors, many of whom have decided not to rebuild.

“It’s really hard because there are so many things to do,” Erickson said. “You feel the stress, and like there’s this time crunch. You have to deal with the cleanup, where you are going to live, whether you are going to be kicked out or not. It’s a real challenge. I talk to my friends and neighbors, and they’re struggling more than they were at the beginning.”

Dr. Ellen Barnett has been hearing it from her patients. The family practitioner, 72, runs a small medical clinic in Santa Rosa. Her waiting room is nearly always full, and most of the people she treats are traumatized. They have anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder, or are struggling with survivor’s guilt. So Barnett writes counseling referrals — more than she ever has before.

It’s a mental health crisis that is sweeping the county. Grief and trauma have had a domino effect, hitting just as the signs reading, “Love is Stronger than Smoke,” and “Sonoma County Strong,” have started to disappear. Many thought they would be moving on with their lives by now. They’re not.

“Every single person in this county was literally, and is continuing to be, traumatized by the fires,” Barnett said. “In some ways, it’s almost easier for some of us — not all of us, but some of us — who lost our homes. We know what we experienced. We have a list of things to do.

“My experience, as a physician, is that it is very difficult for people that didn’t lose their homes to acknowledge they were traumatized. They feel so guilty, that they shouldn’t feel sad, because so many people lost more.”

The Tubbs Fire destroyed Barnett’s home near the Safari West wildlife preserve in the hills north of Santa Rosa. She and her husband, Dr. Bob Dozer, 68, had lived there since 1984. They were both on-call back then — he in Napa County, she in Sonoma County — and it was halfway between the two hospitals. The couple raised three children there, carving tick marks for each year’s growth on the coat closet door.

The night of the fire, they smelled smoke and evacuated to a friend’s home in nearby Larkfield-Wikiup. Later, when the flames threatened that community, too, they drove to their Santa Rosa clinic and slept on the exam tables and in massage chairs. The next morning, they started working, helping to rewrite lost prescriptions.

“I don’t think anybody knows what the full impact of this disaster is on our community yet,” Barnett said. “What is actually going on here in Sonoma County? And what are we in denial about? What are we missing? Those are the bigger questions for me. They’re the hardest questions.”

Those left behind

When emergency crews dug in and finally stopped the advance of the Tubbs Fire at her front yard on Randon Way in Coffey Park, 61-year-old Lisa Mast thanked her great fortune. What a blessing it was to be spared the flames, friends told her.

But there’s a cost to that blessing. Mast and her neighbors on the intact side of the fire line have learned that well in the past six months.

The smoke and ash coated the inside of their homes, and that has required cleanups that can cost $100,000 or more. Dust from the cleared lots across the street is continually blown into the air, and the tiny particulates and potential allergens can be irritating to sensitive respiratory systems. Until recently, cleanup equipment clanked and scraped from morning till night. That’s now slowly being replaced by the din of heavy construction machinery.

Anyone who chooses to stay in the neighborhood, like Mast and her next-door neighbor Anna Brooner, is in for at least 10 more years of ear-banging tractor noise and billows of dust from construction crews.

“We have felt so forgotten, because all the attention has just been going to people who had total losses,” Mast said. “Those total losses are terrible, and you feel bad for everyone — you feel guilty about even asking to be considered alongside them.”

This overlooked anguish has been so acute that another Coffey Park resident, Lani Jalliff, started the support group Standing Homes for everyone in the same straits.

“Friends say, ‘You must feel so good, now that burned houses are all cleared, isn’t that great?’ ” Jalliff said at the first meeting in February, which drew 26 people. Everyone laughed. Ruefully.

Mast is a cancer survivor and has to be extra-vigilant about her immune system. So until late March she was living in a rental unit in Windsor while her two-story house got scrubbed ceiling to floor. It was a huge job — and it still is, with some of that cleaning still going on in corners of the kitchen and her office room. It’s emotionally consuming and takes away time from her work selling medical insurance.

What happens in such a project is this: Industrial air cleaners chug most days in the rooms, month after month. The carpets have to be replaced. The venting systems have to be scoured of airborne toxins.

Just before she moved back in, the overwhelming nature of it all got to Mast as she talked to her sister on the phone, and she broke down crying.

“It’s amazing how long this all takes,” said Mast. “Sometimes it feels like it’s never ending.”

“This was such a great neighborhood to live in,” said Brooner, 58, whose family helped build Coffey Park in 1988 and has lived in it since then. “People walked their dogs, we visited each other, we watched each other’s kids grow up here.”

She stared across the street at the blackened fields that used to hold houses, friends and favorite walking routes. “So much of it is gone now,” she said. “It’s awful. I feel so bad for people who lost loved ones, friend, mementos. I want it all back.”

Signs of life

Slowly, slowly, the county is moving forward. The landscape is unfamiliar, and the victories have been few, but there is hope.

In Coffey Park, residents carved jack-o-lanterns for Halloween and set twinkling fir trees and menorahs in burned-out lots for Christmas. This month has brought Easter egg hunts and the first unfurling of green leaves on burned trees.

In Santa Rosa’s City Hall, block captains from each of the decimated areas gather to compare notes on insurance paperwork, designs, progress.

In the Sonoma County Children’s Museum, special nights have been held for the children who fled their homes, some in the arms of their pajama-clad parents.

Where Supervisor Gorin’s destroyed home stood, daffodils and narcissus are rising.

Lizzie Johnson and Kevin Fagan are San Francisco Chronicle staff writers. Email: ljohnson@sfchronicle.com, kfagan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @LizzieJohnsonnn, @KevinChron

ONLINE

Find videos and interactive elements, plus a podcast with reporters Lizzie Johnson and Kevin Fagan: http://sfchronicle.com/wildfires-aftermath