Academy of Art could face trial in fraud suit

By Nanette Asimov

At the heart of a lawsuit against the Academy of Art University in San Francisco is whether the for-profit school used illegal tactics to enroll students and defraud the federal government out of millions of dollars in financial aid.

For nearly seven years, the nation’s largest art school — and one of San Francisco’s biggest property owners — has succeeded in keeping a jury from hearing the lawsuit that plaintiffs say could cost it nearly a half-billion dollars.

Now the school is running out of options. And unless the case is settled, the Academy of Art is expected to have to defend its practices before a federal jury in Oakland this year.

A similar lawsuit against the online giant University of Phoenix was settled in 2009 for $78.5 million. Another California for-profit company — Corinthian Colleges Inc., which owned the Heald, Wyotech and Everett college chains — shut down in 2015 as federal investigators probed allegations that it defrauded the government.

The case against the Academy of Art began in 2009, when three employees and one former employee approached an attorney with evidence that the school raised their salaries based on how many students they enrolled, reduced their pay if they missed recruitment goals, and dangled trips to Hawaii as an extra incentive.

The federal government bans such “incentive compensation” so colleges won’t enroll unqualified applicants who stand little chance of graduating and being able to pay back their government-backed student loans.

The four plaintiffs, who no longer work at the school, said the Academy of Art did just that. They sued the school in U.S. District Court in Oakland on Dec. 21, 2009, and promptly became federal whistle-blowers, alleging the school was cheating the government out of millions of dollars in student loans and grants. The case remained sealed for a year and a half as government investigators interviewed some two dozen potential witnesses. A judge unsealed the case in June 2011.

But the former employees have yet to testify in court.

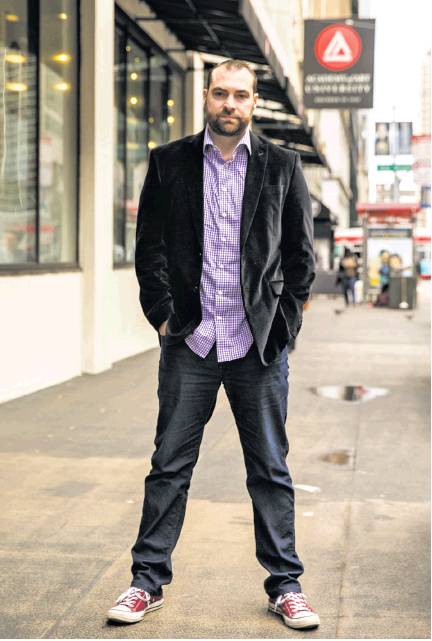

“It’s time to go to trial with this,” said Scott Rose, who worked as a recruiter for the school and is the lawsuit’s lead plaintiff. “I would be thrilled to have the opportunity to tell my story to a jury, or the world in general, so these heartless enrollment tactics are a thing of the past.”

The Academy of Art says the tactics already are a thing of the past — but that when they did occur, they were legal. The school says federal law permitted them under a “safe harbor” provision created by the Bush administration in 2002 and rescinded by the Obama administration in 2010. The legal case covers 2003 through at least 2010.

Safe harbor allowed colleges to reward employees for recruiting students as long as the employees were also judged by other “qualitative” criteria, like work quality and teamwork.

The Academy of Art “stands by its position that the university was in compliance with federal regulations,” said P.J. Johnston, a school spokesman.

Lawyers for the Academy of Art did not respond to requests for comment.

Rose and the other former recruiters — Mary Aquino, Mitchell Nelson and Lucy Stearns — say they can show that the school faked the qualitative measures to evade the ban on incentive compensation.

Their lawyer, Stephen Jaffe, doesn’t fear long-shot gambles. He’s running for Congress to unseat House Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi of San Francisco. He also expects to seek damages of up to $150 million in the Academy of Art case, which could grow to $450 million because he’s suing under the federal False Claims Act.

The act awards triple damages to encourage whistle-blowers to come forward if they believe the government is being cheated. If the former recruiters win, they could keep 30 percent of the damages. The government would take the rest.

Since 2006, the Academy of Art has collected more than $1.5 billion in federal student loans and $171 million in Pell and other federal grants, according to a Chronicle analysis of federal records.

The former recruiters say that those millions motivated the school to vigorously court students and accept all applicants.

“No one was turned away,” Rose said. Some students he recruited were so unprepared to afford the private school that he had to help them find homeless shelters so they would have a place to sleep, he said.

That was a decade ago. Tuition and fees cost nearly $17,000 a year back then, including art supplies, school officials said. Today, that total is nearly $24,000. Student housing — in buildings the school leases from its owners — costs $8,200 to $16,400 a year.

The Academy of Art can keep student loan and grant money if students stay enrolled for 60 percent of the semester, known by staff as the “stick date,” Rose said.

Johnston, the school spokesman, said the Academy of Art has paid out more than $10 million in scholarships over the past six years — evidence, he said, that school officials understand that paying for education can be challenging for many students.

Rose, who was hired in 2006, said a new admissions director at the time created an “incentive program” with recruitment goals that tied the recruiters’ pay to the number of students they enrolled.

“I doubled my salary in a span of less than two years,” Rose said. “I was very good at what I did.”

As for the other legal criteria for winning raises — being a team player and showing up on time — “I’m living proof that they paid no attention to that,” Rose said, recalling what he said were two-hour lunches and Web-surfing sessions.

“I was a terrible employee, except for the numbers I produced,” he said. “And I knew I’d never be fired because of that.”

The 89-year-old Academy of Art has 14,000 students, about twice the enrollment of a decade ago, with a third of the students taking courses exclusively online, according to a 2016 review by its accreditor, the Western Association of Schools and Colleges’ Senior College and University Commission.

The commission renewed the school’s accreditation in 2016 “with notice of concern,” in part because of its low graduation rate. The commission found that of the full-time students who enrolled as freshmen in 2010, just 37 percent had graduated by 2017.

In addition to its position as the largest art school in the country, the Academy of Art University is one of San Francisco’s largest landlords, with 40 buildings throughout the city. Elisa Stephens, 59, owner, president and granddaughter of the school’s founder, Richard Stephens, oversees a family fortune, much of it consisting of properties that for years were out of compliance with the city’s planning codes.

While the code violations vexed some city officials, others, including the late Mayor Ed Lee and former Mayor Willie Brown, now a Chronicle columnist, heaped praise on Stephens, whose art empire does business as the Stephens Institute. The school escaped fines year after year, despite evidence that it illegally transformed affordable residential units into student housing, broke rules on historic preservation and improperly installed its signs.

Ultimately, City Attorney Dennis Herrera sued the Academy of Art and settled in 2016 for $60 million.

Stephens is a society figure who grew up in Hillsborough. She is known for lending classic cars from her extensive collection to civic and charity functions, and pedestrians can see her Bugattis, Packards, Duesenbergs and other roadsters in gleaming showcases along Van Ness Avenue, or up close by appointment.

A 2015 article in Forbes magazine estimated the family fortune at $800 million, and described a chummy relationship between the Stephens family — Elisa and her father, Richard Stephens — and the city’s elite, noting, for instance, that Brown has been a regular guest on the family’s jet and attends the Academy of Art’s annual fashion show. Richard Stephens died in June.

The Stephens family has tried three times to get the lawsuit against the art school tossed out. A judge has refused each time.

Last year, their lawyers filed a mid-case appeal, asking a higher court to make it harder for the plaintiffs to prove their case — and arguing that, even if they could prove it, the loss to the government would be too minimal to be of material importance.

To dispute that assertion, the U.S. Department of Justice sent a lawyer to argue alongside the plaintiffs against the art school at the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco in December.

When the appeals court rules in a month or two, the case is expected to return to Oakland and — nearly a decade after the lawsuit was filed — settle or head to trial.

Whatever the outcome, it is unlikely to help former students like 36-year-old Nicholas, who attended the Academy of Art from 2007 to 2010. He exemplifies the kind of high-risk applicants that the government’s ban on incentive compensation is supposed to protect from schools they can’t afford, and from loans they can’t pay back.

Today, Nicholas has no degree and no transferable credits. But he has plenty of student loan debt.

“I just thought I would go to art school and get really good and become a painter who makes a lot of money,” said Nicholas, who pays so little attention to the federal student loans he owes that he simply estimates it’s $50,000. In default, he hasn’t paid a penny of it — so he asked that his last name not be used.

In 2007, Nicholas searched for art schools on the Internet and liked what he saw on the Academy of Art site. He contacted the school and offered to show the admissions department his portfolio.

But the Academy of Art doesn’t require portfolios and declined, he said. Nor did financial advisers care that Nicholas had a spotty job history and “a little bit” of bad credit, he said.

He didn’t qualify for regular student loans, so the school advised him to take out an “opportunity loan,” Nicholas said. At the time, opportunity loans were offered by the Sallie Mae company to borrowers with bad or zero credit history. In some cases, interest and fees topped 20 percent. The company eventually discontinued them.

The Academy of Art connected Nicholas with Rose, its top recruiter.

“Scott actually tried to talk me out of coming because of the opportunity loan. He said it’s a really dangerous loan. Really high interest,” Nicholas said.

But he was set on attending. He bought a one-way ticket to San Francisco from Krum, Texas, population 4,000. And he took out a $25,000 opportunity loan to cover tuition and a school dorm. The next year he took one out for $16,000, which didn’t cover housing.

Unable to afford city rent, Nicholas couch-surfed with friends or stayed in cheap single-room-occupancy hotels.

He lasted three years before dropping out in 2010, discouraged with the Academy of Art’s courses and costs.

“I never thought about the loans as a bad thing,” he said. “But I traded in my credit to learn how to paint.”

Today he is a street artist selling his work and painting murals. He is still couch-surfing.

Shortly before Nicholas dropped out, one of the recruiters, Aquino, had a financial loss of her own at the Academy of Art.

One day in 2009, Rose said, Aquino dropped by his office and told him the company had sliced her $78,000 salary to $48,000 for failing to meet her recruitment goals. He said she confided to him that she had found an attorney and was considering a lawsuit over the compensation incentive program. Did Rose want in?

“I was making money,” Rose recalled. “But I saw the devastating effects of it. I talked to students about taking out these loans, and the debt they were accruing.

“Most of them would never have a degree to show for it.”

Nanette Asimov is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: nasimov@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @NanetteAsimov