Linking California droughts to ice loss

Research on climate change explains chain of events

By Kurtis Alexander

Californians may have another reason to keep an eye on melting sea ice in the Arctic — at least if they’re concerned about the state’s propensity for plunging into damaging droughts.

Alongside the obvious perils for polar bears and other wildlife, as well as the problem of rising ocean levels, the massive ice thaw thousands of miles away is triggering changes in the atmosphere that are likely to shrink rainfall close to home, according to new research by scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

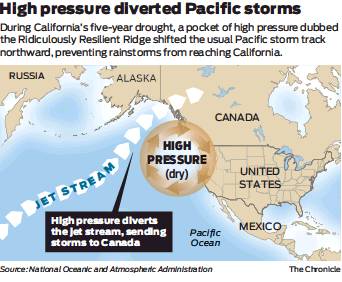

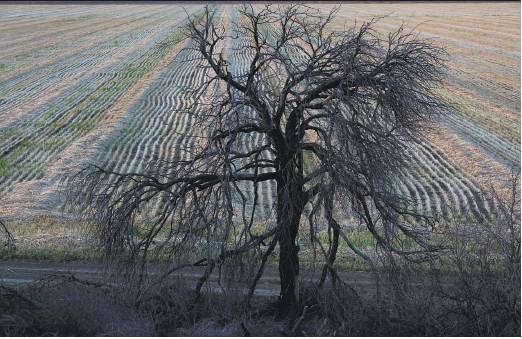

Their study outlines a chain of meteorological events that leads to formation of storm-blocking air masses in the North Pacific. The masses are similar to the so-called Ridiculously Resilient Ridge that kept rain from making landfall during California’s five-year drought, forcing widespread water rationing in homes, prompting farmers to fallow fields and causing the Central Valley to sink due to heavy pumping of groundwater.

The Livermore Lab study, being published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications, doesn’t attempt to explain the recent drought, but to help understand future weather patterns. Still, lead author and climate scientist Ivana Cvijanovic said California should expect more arid periods like 2011 to 2016. As such dry spells become more common, the state will average 10 to 15 percent less rain over the long haul, she estimated.

“The recent California drought appears to be a good illustration of what the sea-ice-driven precipitation decline could look like,” she said.

The study comes amid efforts to understand the relationship between drought and climate change. While higher temperatures are known to increase drying through evaporation, the link between global warming and rainfall has remained in dispute.

Stanford University Earth system scientist Noah Diffenbaugh and UCLA climate researcher Daniel Swain have suggested that upticks in greenhouse gases have created conditions favorable to high-pressure systems, which generally push the east-moving Pacific storm track northward and result in dry conditions in California.

An earlier study by UC Santa Cruz geologist and climate researcher Lisa Sloan went as far as suggesting that Arctic ice loss was helping spawn the drought-inducing atmospheric ridges by channeling warm water south and sending columns of air upward. Her work, though, came under scrutiny because some said it failed to reconcile the changes in the Arctic with the competing influence of the tropics, long thought to be the main driver of Pacific storms.

The Livermore Lab study maintains that Arctic activity is hastening the tropical influence. According to the research, melting sea ice throws enough energy into the atmosphere that it slows the flow of heat from southern latitudes. This results in greater variability in winds and sea surface temperatures as far away as the equatorial Pacific. Much like El Niño or La Niña influences weather on the West Coast, the altered conditions of the tropics due to ice loss favor the development of high pressure systems in the North Pacific.

“The two hypotheses are not at odds,” Cvijanovic explained. “The influence from the Arctic doesn’t go first to California; it goes to the tropics.”

Cvijanovic and her colleagues acknowledge that they’re far from being able to forecast long-term weather patterns for California. However, by incorporating their findings into other models that detail the impacts of climate change, they hope to eventually get a better picture of future precipitation.

“The vast amount of research that is coming out now shows that the Arctic is really inescapable in affecting the planet as a whole, so huge that it can affect so many other locations,” she said. “This can help with planning future water supply in California.”

Kurtis Alexander is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: kalexander@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @kurtisalexander