WINE COUNTRY FIRES

Tracing the origins of 4 biggest blazes

By Evan Sernoffsky

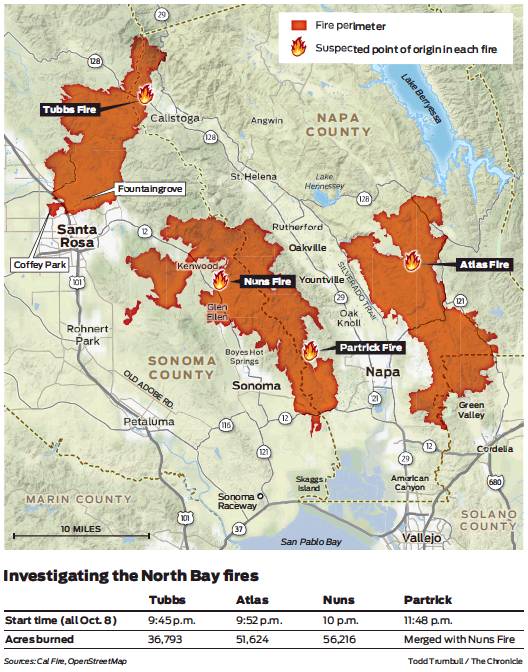

One fire started near a patch of oak trees along a twisting mountain road east of Napa Valley’s famed Silverado Trail. One ignited near a weathered one-lane road through a wooded canyon in Glen Ellen. Another started near a winery in the hills west of downtown Napa. Still another exploded on a hillside among vineyards and historic homes on the edge of Calistoga.

Each of the four now-infamous fires in Napa and Sonoma counties — the Atlas, the Nuns, the Partrick and the Tubbs — spread catastrophically, as did other blazes in Mendocino and Yuba counties. Together, they delivered a horrific toll of death and destruction that spread many miles from where flames first kicked up.

But the points of origin are critically important. With the danger from the fires finally ebbing, teams of investigators have been gathering at these places to sift through blackened soil and debris, inspect scorched trees, talk to those who first reported seeing flames as well as other witnesses, and lay down evidence markers, hoping to piece together the story of how a disaster began.

The areas represent suspected ignition points — at least for now — as identified by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, or Cal Fire.

While that agency and independent experts said it’s too early to speculate on possible causes, the four locations did exhibit some common features: Power lines ran near all of them, and at two locations, downed electric and telecommunications lines and broken tree branches had been surrounded by yellow crime-scene tape.

However, there was no clear indication of what brought lines down at any of the sites. Officials with Pacific Gas and Electric Co., which is responsible for making sure trees are trimmed with at least 4 feet of clearance from its standard electrical distribution lines, said it was premature to comment on the possible cause of the fires, but said the utility company is cooperating with the investigation as it finishes restoring service to customers.

“We’re in the early days,” said Keith Stephens, a PG&E spokesman. “The fire is still burning in places. We’re focused on getting people back up and running right now.”

Cal Fire said nearly a dozen significant fires, including the Tubbs, Atlas, Nuns and Par-trick, broke out around Wine Country and beyond on the night of Sunday, Oct. 8, when wind gusts hit hurricane levels. Several small fires kicked up the following morning and in subsequent days. By the middle of that week, firefighters were battling 25 separate blazes around the region, said Cal Fire Deputy Chief Scott McLean.

In all, this month’s blazes have killed at least 42 people, destroyed an estimated 8,400 structures, burned through nearly 400 square miles of land and prompted 100,000 people to evacuate.

“There are several investigations going,” McLean said. “Our investigators are meticulous and thorough. We want to find that cause. The public depends on us to do our job.”

Veteran wildland fire investigators said drawing conclusions about causes this soon after a fire would be misguided.

“You have to look at all the other potential causes,” said U.S. Forest Service Special Agent in Charge Kent Delbon, who oversees investigations in the Rocky Mountain Region and is not involved with the California fires. “Like with everything, you want to get it perfect. You want every potential investigative lead followed.

“What we do is start with the big picture,” he said. “We walk the outskirts of the fire and start to look at all the other potential indicators. Were there railroad tracks, power lines, a dozer nearby?”

There is no singular or even dominant cause of California wildfires, according to a Cal Fire report on the more than 3,200 ignitions counted in state jurisdiction in 2015, the latest year available. Debris burning accounted for 14 percent of fires and was followed by lightning, electrical systems like power lines, arson, vehicles and sparks from equipment like lawn mowers.

At each of the suspected origin sites for the four worst fires in Sonoma and Napa counties, investigators placed small yellow, red and blue stake flags mapping burn patterns, as surveyors took measurements.

They were, experts said, likely looking at key indicators such as how fire burns against pine needles, grass and trees, and whether the flames were advancing or backing up. The idea is to vector backward and locate a general origin location, before isolating a specific origin site perhaps 20 square feet or smaller, Delbon said. Investigators then start the detail work, sifting though dirt for cigarette butts or other incendiary items.

Power lines, like the ones laying amid burned branches and grass at some of the suspected origin points in Napa and Sonoma counties, can start fires in a variety of ways, experts said. Wind can blow trees or branches into the lines, causing sparks as they’re dragged to the ground. Investigators would look for char marks on the lines or branches, and search for evidence like pieces of melted metal from the wires that could have fallen from above.

PG&E said that anytime a tree or anything else causes a disruption to the electrical system, the company documents the incident in an electronic report that is submitted to regulators at the California Public Utilities Commission. The information is valuable to fire investigators, who will often subpoena such records to help determine whether power lines might have sparked a fire.

The hunt for causes could last months.

Atlas Fire

Ray McLain, 80, was about to take a shower in his home on Atlas Peak Road, a few miles northeast of downtown Napa, when the power cut out around 9:30 p.m. on Oct. 8. Moments later, he said, the lights flickered on and everything seemed to be back to normal. He took his shower and got in bed, forgetting the outage as he drifted off.

But minutes later, he and his wife were peeling out of their driveway as a wall of flames advanced on their home. His stucco house and vineyard remarkably survived, but many of his neighbor’s homes didn’t. The Atlas Fire would go on to kill six people, burn more than 51,000 acres and ruin at least 741 homes, wineries and other structures in Napa and Solano counties.

As McLain and his wife fled that night, they looked across the street at the home of 100-year-old Charles Rippey and his wife Sara Rippey, 98, engulfed in fire. The couple didn’t survive.

“I thought, ‘Poor Sara and Charlie,’ ” McLain said in an interview on his property.

As he spoke, investigators 5 miles up Atlas Peak Road were focused on a small area along the road marked off with yellow tape, reading, “Crime scene do not cross.” They wouldn’t identify themselves, but they asked a reporter and photographer to give them space and not disturb the scene, which was well north of the still-evacuated Silverado Resort and Spa on the isolated road that runs roughly parallel to the Silverado Trail.

“We’re investigating the cause of the fire,” one said.

They were looking closely at a line of oak trees whose branches extended through overhead utility lines on the west side of the road, less than a quarter mile south of a sprawling ranch on the plateau of the Napa peak. A twisted, fallen wire lay on the ground, surrounded by stake flags. A broken oak branch precariously dangled overhead among the wires and other branches.

PG&E crews have been scrambling in recent days to replace more than 1,500 damaged power poles and lines inside the many burn areas since the fires ravaged their equipment. The company’s crews on Atlas Peak, though, were kept away from the investigation scene, and worked farther up and down the road to replace equipment.

Even though Cal Fire hasn’t said anything about the cause of the Atlas Fire, residents like McLain are coming to their own conclusions.

“It was very, very strong and gusty that night,” he said. “I think a tree branch broke and landed on a power line.” Tubbs Fire

Paul Block owns and operates Wine Barrel Furniture on the east side of Highway 128 to the northwest of downtown Calistoga, near where the Tubbs Fire sparked around 9:45 p.m. that Sunday. Hearing the fire’s roar, he looked north out beyond a vineyard across from his shop and saw a hillside along nearby Bennett Lane engulfed in fire.

“Everything was flicking orange, and flames were 40 to 50 feet high,” recalled Block, 49. “I heard a transformer explode in the fire. It looked like a firework.”

Pushed by high winds, the Tubbs Fire would race more than 15 miles to the west, all the way into northern Santa Rosa, where it leveled whole neighborhoods while jumping Highway 101. The blaze, the most destructive in modern state history, killed 22 people, burned down an estimated 5,300 homes, businesses and other buildings, and forced the evacuation of two hospitals.

Back in Calistoga, investigators had the hillside taped off on a recent day as they walked the grounds of several properties. At least one home had been destroyed. Stake flags were set up in a clearing on the scorched hill, but access to the investigators’ work farther up the hill was blocked by authorities.

Less than a mile down Bennett Lane, Bruno Solari said he saw the fire burning the same hillside in its early moments.

“The wind was howling,” he said. “There were some of the strongest winds I’ve ever felt. It was blowing sand and pebbles and small stones.”

Several homes around his burned, he said, when the fire doubled back in his direction the morning after it began. His historic home, built in 1880, was spared.

“We just got extremely lucky,” he said.

Nuns Fire

The suspected origin point of the Nuns Fire, which has been linked to the deaths of a person in Sonoma County as well as a water-truck driver who crashed while on duty in Napa County, is less than a half mile northeast of Highway 12 in Glen Ellen, up run-down Nuns Canyon Road.

There, investigators were looking at a small patch of land along the heavily wooded road near the Relais Du Soleil ranch-style inn.

Next door was the shop of Burning Man sculptor Bryan Tedrick, which was flattened. A massive, partially completed metal horse reared defiantly from the heap of debris.

Across from Tedrick’s shop, over a wooden bridge crossing Calabazas Creek, investigators took photos of burned tree branches and what appeared to be a downed power line marked as evidence. Farther up the one-lane route, overhead wires crisscrossed through a canopy of thick trees before ending at a snapped-off, unburned wooden utility pole that lay over the creekbed.

Alexa Wood’s family owns Beltane Ranch on Highway 12 in Glen Ellen, about a quarter mile away. Her daughter called 911, she said, when the two of them saw flames creeping up the back of their property around 10 p.m. that Sunday. The following two hours were a blur as the family battled to save their ranch, which mostly survived thanks to their quick work and help from arriving firefighters.

“It was absolutely crazy,” Wood said in an interview at the ranch, which was built in 1892. “The sparks were thicker than any snowstorm you’ve seen. They were flying parallel to the ground. Piles of dried horse manure were igniting like little bombs. Boom, boom, boom.”

Wood’s son, 35-year-old Alex Benward, grabbed a vineyard tractor and plowed firebreaks while other family members bailed water from horse troughs to douse flames. The historic home on the property, which the family runs as a bed and breakfast, was filled with guests, and Benward put two couples in his 1972 Ford Bronco, instructing them to drive to safety.

Remarkably, only a couple of small outbuildings on the property burned. No animals died. But whole neighborhoods to the west, along Warm Springs Road, were wiped out. The Nuns Fire prompted the evacuations of several communities and joined up with other, smaller fires to become a sprawling blaze covering more than 56,000 acres.

Partrick Fire

Late that Sunday, as wildfires burned around the North Bay in an unfolding disaster, members of the Fontanella family thought they were safe at their picturesque winery property on the south slope of Mount Veeder along rural Partrick Road in Napa County, between the cities of Napa and Sonoma and north of the winemaking area called Carneros.

Co-owner Karen Fontanella was in Boston, while her husband, Jeff Fontanella, stayed at home with one of their sons. They later told her the story of the fire’s first spread at about 11:50 p.m.

“The lights started to flicker and then the lights when out,” she said. “The (electric) gate wouldn’t open, and when my husband looked out back, there were flames.”

The estate’s vineyards survived after the fire scorched 65 of the family’s 80 acres as it tore south, then doubled back toward the mountain. The inferno burned for days, leveling homes along Napa Road covering more than 10,000 acres on its way to merging with the Nuns Fire to the northwest.

The Chronicle couldn’t access the spot where the investigation was occurring, because it was on private property and wasn’t visible from the road. But on a recent day, Cal Fire investigators looked at downed power lines behind the Fontanella property, where the family first saw the fire, Karen Fontanella said.

Chris Sarley, who has a ranch to the north of the winery where he keeps alpacas, sheep, donkeys, llamas and a variety of dogs, said he heard the fire started when a tree hit power lines near the Fontanella estate. Firefighters used his sprawling property as a staging area as they drew water from his pond to fight the flames through the first morning.

“I watched the ridge burn all night,” Sarley said. “It was a big event.”

Evan Sernoffsky is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: esernoffsky@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @EvanSernoffsky