Net Worth

Study using fake resumes shows age and gender discrimination

KATHLEEN PENDER

In the largest study of its kind, a trio of economists found “compelling evidence” that older workers, especially women, experience age discrimination in hiring, according to a summary of the research published Monday by the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank.

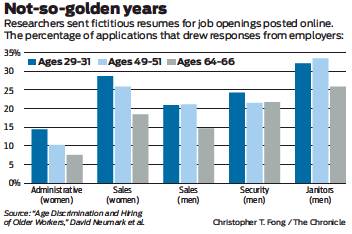

The researchers created more than 40,000 fake resumes that were identical except for age and gender and submitted them online for more than 13,000 mostly lower-skilled jobs. It found that response rates went down as age went up, and the disparity was higher for women than men.

The report comes when the percentage of the U.S. adult population age 65 and older is projected to rise sharply, which will increase the ratio of non-workers to workers and strain the Social Security system.

Policy efforts to improve the system’s solvency have focused on encouraging seniors to work longer by changing Social Security benefits, such as by reducing benefits for those who start claiming them at age 62. “If they work longer, they pay more Social Security taxes,” said lead author David Neumark, an economics professor at UC Irvine and visiting scholar at the San Francisco Fed.

However, “if businesses don’t respond to the policy-induced larger labor supply by hiring older workers, it could lead to even harsher policy reforms for seniors,” the report says.

Age discrimination is difficult to prove, so the researchers set up what’s known as a correspondence study. They created “realistic but fictitious” resumes for job applicants who had identical backgrounds and differed only by age and gender. Age was indicated by including the applicant’s high-school graduation year.

They had otherwise identical workers who were young (ages 29 to 31), middle-aged (49 to 51), and older (64 to 66) apply online for more than 13,000 actual positions in 11 states in 2015. There were more than 40,000 applicants, making it “by far the largest” correspondence study to date, the report said.

The researchers sent female resumes to openings for secretaries and administrative assistants and male resumes to help-wanted ads for janitors and security jobs. Both genders fake-applied for retail sales positions. Low-skilled jobs were chosen because employers are more likely to be familiar with applicants for high-skilled jobs and ignore ersatz ones.

“Across all five sets of job applications, the callback rate was higher for younger applicants and lower for older applicants, consistent with age discrimination in hiring,” the report said.

The oldest group of female applicants for administrative jobs had a callback rate of 7.6 percent versus 14.4 percent for the youngest group. In sales, their response rates were 18.4 percent versus 28.7 percent, respectively.

For male job applicants in sales, security and janitor jobs, “there is also a lower callback rate for older men in general,” but the difference was “not as consistent or pronounced” as it was with females. For sales jobs, the oldest male applicants had a callback rate of 14.7 percent versus 20.9 percent for the youngest group.

“Our field experiment provides compelling evidence that older workers experience age discrimination in hiring in the lower-skilled types of jobs,” the report said. “This evidence implies that there are demand-side barriers to significantly extending work lives.”

Angela Gyetvan, a freelance digital media consultant who used to work in Silicon Valley but now lives in Los Angeles, is not even close to 65 (she won’t let me publish her exact age). But she says she has experienced age discrimination. “I work primarily with emerging businesses,” she said. “When they think of you as a full-time employee, they want people who will work like 35-year-olds. If you come in as a consultant, they listen to you more. They are more aware of the money they are handing to you. They are more accepting of the fact that you have more maturity. It’s one of the reasons I’ve kept consulting. In this path, I don’t face as much ageism.”

Gyetvan says the “gig economy” could be a solution for some older workers. However, two weeks after she was laid off from her last full-time job, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. After Cobra coverage under her previous employer’s plan ran out, she was able to purchase individual health insurance because the Affordable Care Act forbids insurance companies from denying coverage or charging more because of pre-existing conditions. If the Affordable Care Act, or that part of it, is overturned, workers who are not yet 65 and eligible for Medicare could have problems working independently.

Proposals to shore up Social Security by encouraging longer careers include increasing the so-called full retirement age (from 66 to 67 for people born since 1943), reducing benefits for those who claim them before age 62 and eliminating the retirement earnings test. This test withholds some Social Security benefits from people who are working and claiming benefits between age 62 and their full retirement age if their earnings exceed a certain amount.

The bigger problem is figuring out how to incentivize employers to hire older workers.

“It’s still the case that age discrimination is not even close to the same taboo as other forms of discrimination,” Neumark said. “People tell age jokes who would never tell race jokes.”

The federal Civil Rights Act prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin. The laws that prohibit discrimination on the basis of age and disability are slightly different.

“There is one tool we don’t use with respect to age that we do use with respect to race and gender — affirmative action,” he said. For example, federal contractors are required to set goals to end any underrepresentation of women and minorities. Why can’t such goals “be symmetrical,” he asked, and apply to older workers as well?

Also, states can adopt antidiscrimination laws that are stronger than federal law. In states that have, “work I have done shows that you had more people working to older ages,” Neumark said.

Another solution is to “allow larger damages in age-discrimination suits and extend the (age-discrimination) law to smaller firms.”

The federal Age Discrimination in Employment Act, which prohibits employment discrimination against persons 40 or older, applies to companies with 20 or more employees. California’s age-discrimination act applies to employers with five or more employees. Some states have applied age-discrimination laws to all employers.

In a longer paper on his research, Neumark mentioned some theories as to why employers might discriminate against older workers. It could be that “some physical capacities” can decline with age, although “some capacities may increase with age.” Also, “employers might expect older workers to have health problems, which could raise absenteeism or pose accommodation costs.” Finally, employers might expect that older workers would be near retirement, and be less willing to invest in them.

As for why older women fared worse in his study than men, he had no evidence but said it could be that “appearance matters in our sample of low-skilled jobs, and the effects of aging on physical appearance are evaluated more harshly for women than men.”

“We think it’s sad that discrimination happens at the resume stage,” Nancy McPherson, AARP’s state director in California, said in response to the study. AARP is using “education and outreach” to “demonstrate the value that older employees bring,” she said. As people live and work longer “it’s common to see four and five generations working side by side. It’s a unique opportunity to leverage different perspectives and approaches.”

Kathleen Pender is a San Francisco Chronicle columnist. Email: kpender@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @kathpender