OAKLAND HILLS INFERNO 25 Years Later

Fire next time? Question probably is when, not if

Drought and unchecked eucalyptus growth have increased risk of repeat

By Rachel Swan

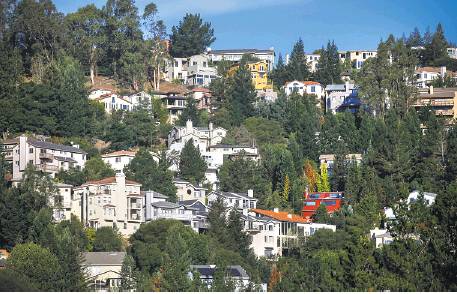

Twenty-five years after a horrific firestorm killed 25 people and wiped out nearly 3,500 homes in the Oakland hills, the conditions are ripe once again for a similar — if not worse — disaster.

The 1991 inferno led to improved policies and equipment for fire and emergency crews, as well as fire-proof materials on homes and roofs. But the highly flammable trees that fueled the blaze have since regrown, and an ongoing legal battle has thwarted the city’s efforts to remove them.

“I go with what the Australians say about eucalyptus — they call them ‘gasoline on a stick,’ ”said Susan Piper, who is still haunted by a searing image from her escape on Oct. 20, 1991: A grove of eucalyptus trees aglow in flame exploded just yards from where she sat in her family van, stuck in traffic with her 9-year-old daughter.

Though some residents still hold painful memories of the fire, a few of them stoutly oppose a tree-cutting effort that many fire experts say is the best way to prevent future disasters.

As a result, the hills are still dotted with thousands of towering eucalyptus, most of them older and more brittle than they were in 1991.

Conditions in the fire-hazard area, which runs mostly above Highway 13 and Interstate 580 from Highway 24 south to San Leandro, have gotten worse, said Robert Doyle, general manager of the East Bay Regional Park District, largely due to the drought but also because of the failure to remove brush and trees.

“We have a worse drought, more dead trees and drier hillsides,” Doyle said. “Emergency crews and fire departments are very concerned, and in the meantime we have this squabble that’s preventing progress.”

Although firefighting equipment has improved since 1991, the city hasn’t been able to cut down eucalyptus and Monterey pines from the ridgeline because of the steadfast opposition of some residents.

Last year, six neighbors who call themselves the Hills Conservation Network sued the Federal Emergency Management Agency and landowners UC Berkeley and the city of Oakland, accusing them of unfairly “clear-cutting” eucalyptus, Monterey pines and acacia trees. The group claimed that thistle, hemlock and poison oak would replace the felled trees, creating a greater fire risk. The East Bay Regional Park District was also named in the suit.

Dan Grassetti, who heads the Hills Conversation Network, said his group advocates a “species neutral” approach — a term that angers many experts, who blame eucalyptus and other invasive species for spreading the 1991 fire.

“Eucalyptus are highly flammable, so, essentially, we have huge plantations of fire-creating materials,” said Norman La Force, chair of the Sierra Club’s East Bay Public Lands Committee. “And people in the Hills Conservation Network just don’t believe that.”

FEMA settled the lawsuit in September when the federal agency and the state’s Office of Emergency Services agreed to withhold $3.5 million grants to UC Berkeley and Oakland, which would have funded tree removal. The agency still will set aside $2.6 million for EBRPD to cut brush and eucalyptus on 540 acres from Point Pinole to Chabot Regional Park.

Yet even that money could be threatened because of a second lawsuit. The Sierra Club also sued FEMA last year in U.S. District Court in San Francisco, claiming the agency’s fire prevention plan didn’t go far enough. The Sierra Club wants the eucalyptus along 1,500 acres of ridgeline removed to make way for a native forest.

The litigation over competing environmental philosophies has cost the city, university and park district hundreds of thousands of dollars, said Doyle of the parks agency.

Some residents, particularly those who survived the 1991 blaze, are growing anxious.

Barry Pilger and Catherine Moss, real-estate brokers who lost their home on Buckingham Boulevard to the fire and have since rebuilt, are fed up with what they see as mulish resistance by a small group of activists.

“They’re a group of about half a dozen people, all self-appointed experts, who have come up with their own version of a flat Earth society,” Pilger said of the Hills Conservation Network.

Grassetti said his group’s six-member board includes five survivors of the 1991 fire and that members are just as concerned about fire as everyone else. He said federal money was being misspent “to advance a native-plant agenda.”

But La Force and other ecologists say kindling in the hills has increased over 25 years. There are at least as many eucalyptus trees in the hills as there were in 1991, said UC Berkeley Prof. Scott Stephens, who specializes in fire ecology. The trees propagate quickly: A burned or chopped stump can spawn several shoots at its base, and each of those can grow to be 40 feet tall and 10 inches thick within seven years, he said.

Today’s trees are older, with long, ribbony bark that breaks off and forms dangerous embers during a wildfire, Stephens said. Drought, periodic freezes and beetle infestations have made the bark more feeble.

“We’ve got these trees suffering in the hills, and the Caldecott acting as a natural wind tunnel,” said Piper, who now chairs the Oakland Firesafe Council, a neighborhood group dedicated to wildfire prevention. “And every 20 years or so, something gets really bad on those hot, windy days.”

The East Bay Regional Park District is moving forward with its own plan to thin the eucalyptus in Tilden Park, Claremont Canyon and Chabot Regional Park — a sprawling, 3,000-acre swath of land — using funding from a $12 annual parcel tax in Alameda and Contra Costa counties.

Without federal grant money for clearing vegetation, Oakland has focused on regulations. Since 1991, the city has tightened building codes for houses in the hills, requiring residents to use nonflammable roofing materials, cover eaves to keep embers from blowing in, and build the exteriors of new homes with fire-resistant material. Ten years ago the city also passed an ordinance to require sprinkler systems in any new construction in the fire hazard area.

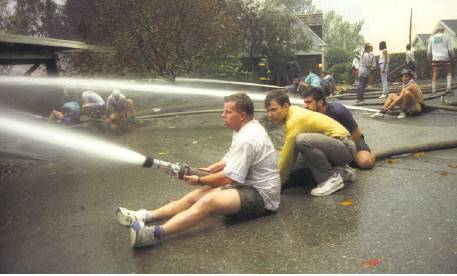

The Oakland Fire Department has also acquired new fire engines equipped with all-wheel drive, and purchased better radios to communicate with outside agencies. Oakland has standardized its fire hydrants so engines from other areas can hook up their hoses.

Since the 1991 fire, the department also has conducted annual home inspections in the hills and provided brochures on vegetation management.

Getting people to comply has been tough because most residents weren’t there in 1991, said Deputy Fire Chief Mark Hoffmann.

Pilger and Moss led a successful 2003 campaign for a 10-year tax, which generated about $1.6 million annually that pays for city inspections, debris removal and goats to graze on grass and brush. Their bid to renew the tax lost by a handful of votes in 2014.

Grassetti, who opposed the tax, said it was “mismanaged” by people who support native-plant restoration and want to cut down eucalyptus.

Pilger said no tax money was spent on chopping down trees.

The constant wrangling has frustrated Hoffmann, who fought the blaze as a lieutenant in 1991 and is still rattled by his memories of that scorching fall day.

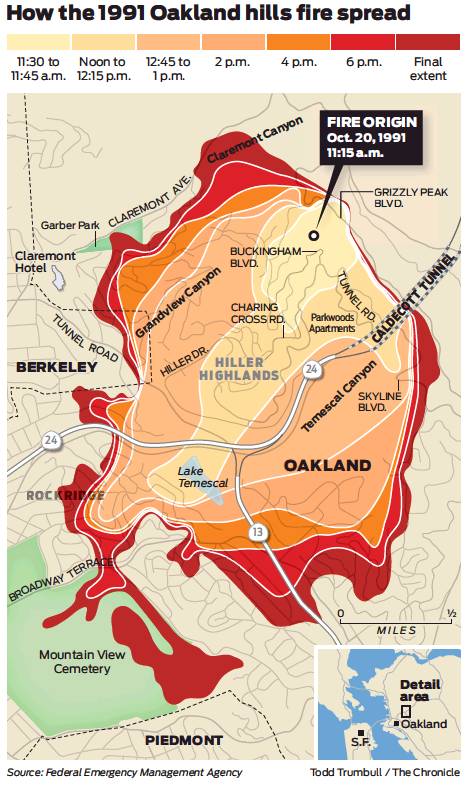

The firestorm had its origins in a small grass fire the previous day near Charing Cross Road. Firefighters thought they had knocked it down, but when Diablo winds howled out of the east the next day it sprang back to life and turned into an uncontrollable inferno.

The father of Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf lost his home in the fire, and spent years replacing all his possessions. Among the people who died were Oakland police Officer John Grubensky and a Fire Department battalion chief, James Riley.

“You have this fight going on in the hills, and people complaining that we’re trying to clear-cut the parks,” Hoffmann said. “As we get further away from the firestorm there are people who weren’t there when the fire happened, and they say, ‘We like our shady glade, we like our canopy of trees.’ ”

But another giant firestorm is inevitable because wildfires ignite in the Oakland hills about every 20 or 30 years, he said. When that small grass fire flared back 25 years ago, fire crews were already at the scene but were unable to stop it from spreading.

“It’s not a question of if, it’s a question of when,” said Moss, who remembers a moonscape where her home had been. “There were dead animals, fire hydrants drizzling, and all the power lines were down. We didn’t know where we were because all the landmarks were gone.”

Piper, who also rebuilt her house, remembers looking at a landscape where only chimneys remained of neighbors’ homes.

“It’s almost surreal, being in the middle of a disaster,” she said. “But picking up the pieces afterward — that’s surreal, too. And that’s an experience you don’t want anyone else to have to go through.”

Rachel Swan is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: rswan@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @rachelswan