Guadalupe lakes to be emptied

By Josh Baugh STAFF WRITER

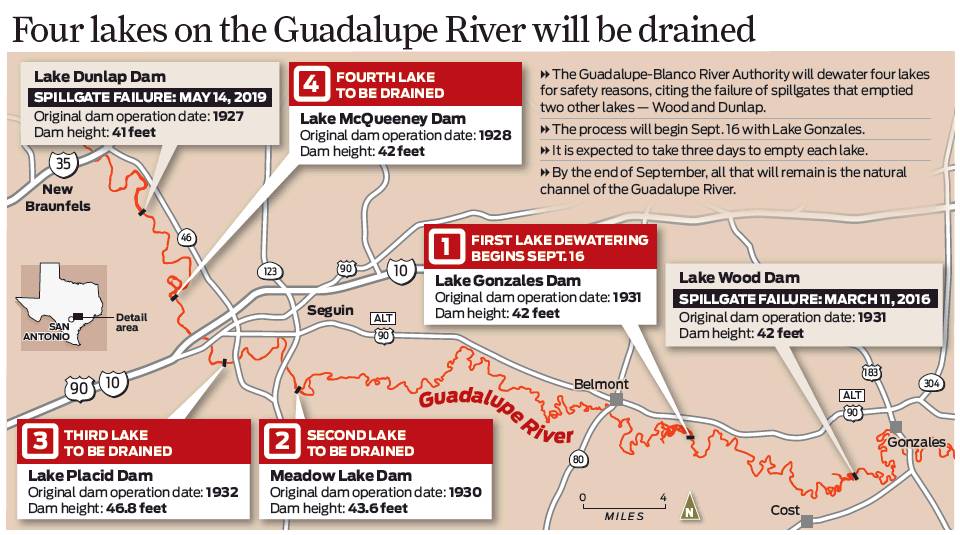

The Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority will drain its four remaining lakes on the Guadalupe next month, citing the imminent public danger posed by the decrepit condition of spill gates in its 90-year-old dams.

The lakes will be dewatered one by one beginning Sept. 16. Officials expect each lake to take about three days to empty. The process will start with Gonzales on the east, then move west to Meadow, Placid and finally McQueeney, the most populated one.

The water level will drop by 12 feet on each lake, leaving only the river’s natural channel. Two other lakes in the chain, Dunlap and Wood, already have drained after their spill gates failed.

The GBRA notified associations of lakefront residents Thursday about the decision and is sending about 2,000 certified letters to all property owners.

The dewatering of the lakes will mark the end of an era. Originally impounded in the late 1920s and early ’30s, the lakes and their dams were used to produce electricity. In the ensuing years, the lakes became centers of recreation as power generation faded.

For some property owners, the lakes are their homes. For others in San Antonio and Houston, they’re weekend vacation spots for boating, fishing and skiing. Businesses such as bait stands, gas stations and restaurants emerged. Property owners say all that could wither once there’s no water left in the lakes.

Whether all six dams could be fixed and the lakes restored remains uncertain. It could take at least several years and cost $180 million.

Until there is a solution, GBRA officials said they can no Failing spill gates

Since 2016, spill gates on two GBRA dams have failed: first at Lake Wood, then at Lake Dunlap on May 14. Video from a security camera at Dunlap captured the middle spill gate — an 85-foot-long, 12-foot-tall wall of steel and timber — lurching up and out before crashing down into the river.

“There is no reason for us to believe that any of the gates could not do that at any given moment,” Kevin Patteson, the authority’s general manager and CEO, told the San Antonio Express-News Editorial Board. “And that’s what keeps us up at night.”

The agency has posted signs and used other methods to deter people from entering unsafe areas. Buoys marked with “Keep Out” float in the channel, along with a large sign that reads “DANGER: STAY OUT OF WATER. RESTRICTED AREA.” Loudspeakers alert the public to leave immediately and say that law enforcement has been contacted.

The warnings haven’t always been heeded. A video from late July, for example, shows people in kayaks and boats and on paddle-boards bumping up against the spill gates at Nolte Dam on Meadow Lake and in some instances climbing on the dam itself.

The decision by GBRA staff to empty the lakes does not require approval from the agency’s board of directors, whose nine members are appointed by Gov. Greg Abbott.

Last month, the agency hinted that draining the lakes could be necessary, even if temporary, so engineers could inspect the dams and assess the spill gates’ soundness.

Property owners from the lakes lambasted the proposal. They packed into the GBRA’s Seguin headquarters for the July meeting of its directors and demanded that the spill gates remain up. Draining the lakes would disrupt their way of life, drive down property values and ruin businesses around the lakes, they said.

The property owners at McQueeney were mostly unmoved by engineering studies and modeling that showed potentially life-threatening inundation of popular recreation areas if the three spill gates in that dam were to fail. They told GBRA officials they doubted such a scenario would actually unfold, pointing to the failure of a single spill gate at Dunlap — not all three there.

Threat to life remains

Patteson said there’s the potential for loss of life even with a single spill gate failure if people are nearby when it happens.

“We’ve put up every safety measure we can think of, and we still see kids climbing over them, and down them and on them,” he said. “We’ve been put on notice we have something that can hurt somebody, and we have a way to alleviate it. And that’s what a responsible organization would do.”

Patteson said Wednesday that the GBRA is in the midst of a delicate balancing act. The authority is giving property owners ample time to move their watercraft from the lakes before the water drops low enough to make that difficult, if not impossible.

At the same time, the public notice gives disgruntled property owners time to ask the courts to block the GBRA from dropping the lake levels. Patteson said he expects that there will be an effort to seek an injunction against the GBRA. Even if one is granted, he said, it doesn’t reduce the chances of another catastrophic spill gate failure.

Property owners will have until at least Sept. 16 to remove their watercraft from the lakes. Most homes along the lakes’ shores have their own docks where boats and jet skis are stored.

When the Lake Dunlap spill gate failed without warning in May, residents watched the water recede, exposing large mud flats for the first time in almost a century. Boats were left stranded, with some dangling in the air in slips that elevate them over the lake.

Once the flats dried out, boat owners had to use tractors and trailers to move their watercraft to the river channel, then drove them to an extended makeshift boat ramp for removal.

Now, grasses are filling in areas that once were underwater.

A ride around the lake

Reaction to the GBRA’s announcement Thursday ranged from surprise to dismay to defiance. Some property owners were struck by its abruptness and finality. The agency’s staff controls operations, not the board of directors. Still, the board didn’t convene another public meeting to get more community input.

Mark Long, Lindsey Gillum and Bob Spalten — members of the Friends of Lake McQueeney Association who’d been on a committee working with GBRA officials on possible solutions to the dam crisis — said they were taken aback.

“We’ve had an open dialogue working with the GBRA and their administration for a couple months now and had been working pretty closely with those folks trying to come up with some engineering studies, among other things,” Long said. “It was a bit of a shock to us that that decision had been made without consultation with us or the other lake associations.”

They agree with the GBRA’s concern about the public’s safety but think the agency could do more to protect people on the water short of draining the lakes.

Gillum said the caution signs are insufficient and that the added warning buoys are easily mistaken for “no-wake” buoys commonly seen on the lakes. She suggested that the GBRA could boost security by placing employees or law enforcement officials equipped with bullhorns at the dams or in boats.

Spalten said it’s “to be determined” whether the lake association signs on with McQueeney property owner and Houston attorney Doug Sutter, who said he is seeking injunctive relief from the courts to prevent the GBRA from draining the lakes.

“We have to do some more studying on our own,” Spalten said.

Sutter thinks the agency should be forced to fix the dams, using whatever money it has — even if it comes from the GBRA’s water and wastewater services revenues. De-watering the lakes will ruin property values, he said.

“How are you going to sell your house?” he said. “That’s the problem with it. Already, people are withdrawing contracts they had on houses.”

Lisa Thomson, a real estate broker and McQueeney resident, said she and her husband are rethinking whether to buy a neighboring home as an investment.

After she learned Thursday morning that McQueeney would be gone in a matter of weeks, she asked her husband to take her on a boat ride around the lake.

“I cried about the potential loss of our beautiful lake for the next hour as I looked at all the homes and thought about the impact on the homeowners’ families,” she said.

Downriver, Kevin Skonnord, president of Citizens United for Lake Placid, said he wasn’t surprised by the GBRA’s decision, though “it’s definitely disappointing. Obviously, in 30 to 40 days, there will be no water in McQueeney and Placid.”

He understands that the GBRA’s utmost concern has to be the danger posed by another spill gate failure. If anything, he said, draining the lakes could intensify the sense of urgency among property owners to find a long-term solution to ensure that the lakes return one day.

Uncertain future

What that solution would be is as uncertain as the effect on real estate values.

Some have predicted a loss of as much as 50 percent, though appraisers have said it’s too soon to tell. Jonathan Stinson, the GBRA’s deputy general manager, estimated that property around Dunlap, McQueeney and Placid is worth $1 billion, half of it at McQueeney alone.

Fixing the dams and restoring the lakes, according to the GBRA, would entail an overhaul of the spillgates — replacing the antiquated “bear trap” mechanisms with modern hydraulic ones — and redoing the dam structures themselves. Not everyone is convinced that a total retrofit is necessary, especially given the estimated cost of $180 million for six dams.

Some property owners appear willing to accept some financial responsibility for the undertaking, if only to preserve their lifestyle and property values. The GBRA, a state-created authority, has no taxing powers and depends on revenue it produces to cover costs. With a 10-county jurisdiction along the Guadalupe, the agency services a rapidly growing area and makes money from water sales and wastewater treatment.

But officials say the agency has no authority to use those funds to repair the dams. Its ratepayers for water and wastewater services could go to the Public Utilities Commission, a regulatory agency, and challenge such spending, and they likely would win, Patteson said.

“There is a path forward, but it’s not going to be easy,” Patteson said. “It’s not going to be quick. And it’s not going to be cheap.”

The GBRA is working with homeowner associations interested in creating special taxing districts with the authority to tax property owners to help cover the cost of rebuilding the dams and restoring the lakes.

One is the Preserve Lake Dunlap Association. It plans to call an election for the creation of a water control and improvement district and has targeted the Nov. 5 ballot. But it may miss state deadlines for that election.

The associations are expecting assistance from the GBRA and other governmental organizations to help cover the cost. But Patteson said Wednesday that it’s possible not all six dams would be fixed. The lakes farthest downriver — Gonzales and Wood — don’t have enough property value to cover the cost of debt service and may ultimately seek aid from the state or federal government.

Once the lake levels drop, it will be a minimum of several years before they return, if ever.

“It’s going to be a long time. … One of the hardest things we’ve been struggling with in the past three years is there’s not really a funding solution at the state or federal level for this issue,” Patteson said. Even “if you have the funding today, it takes about a year of engineering and about 24 to 28 months of construction.”