His success story started with books

By Alyson Ward STAFF WRITER

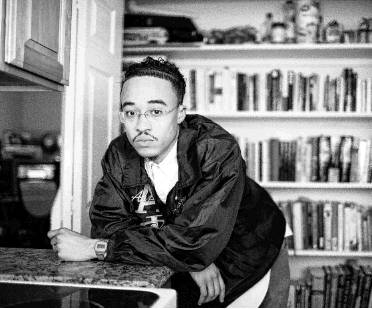

The right book, Dieter Cantu believes, can change your life.

When he was growing up in San Antonio, getting shipped off to foster care and sent to live with relatives, he never had the books he was hungry to read.

“I was always interested in things,” Cantu said. “I didn’t just have access to learn about those things.”

In his teens, Cantu spent four years in the Texas juvenile justice system after pleading guilty to aggravated robbery.

He landed at three different detention centers, but the only books he could find were outdated, fiction or written for kids — nothing that fed his hunger for practical knowledge.

Today, at 28, Cantu has a career and a college degree. And in the past year, he has collected thousands of nonfiction volumes to fill the shelves at juvenile detention facilities and underserved libraries.

Cantu wants teens to get out of juvenile detention and do something good. Books, he says, can help them change their lives.

Cantu thought up his Books to Incarcerated Youth Project after visiting detention facilities as a guest speaker.

He moved to Houston last year and now works as a program manager for the Harris County Youth Collective, which focuses on “dually involved” youths who are served by Child Protective Services while being part of the juvenile justice system.

But outside his job, he’s invited to speak regularly to the kids at youth detention centers, since he’s been in their shoes.

When he was 16, Cantu was in a car with three older friends as they rode around downtown San Antonio, robbing people at gunpoint.

The police picked them up at a red light, and Cantu — the only minor in the group — quickly pleaded guilty, so he could avoid being tried as an adult. He was sentenced to 10 years in juvenile detention.

In the four years he served, Cantu said he escaped into books. But he remembers being hungry for the volumes he couldn’t find — the ones that would help him directly and maybe make up for his lack of access to Google.

“I wasn’t interested in the ‘Harry Potters’ or the ‘To Kill a Mockingbirds,’ things like that,” he said. “But I was interested in how to start a business, how to become an entrepreneur. Psychology. Theology. Finance.”

He wanted to do something substantial and lasting. So last year, he started asking for book donations.

Cantu, who pledged the Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity in college, has enlisted the help of his fraternity brothers at college chapters all over Texas.

They’ve helped him gather book donations at the University of Houston, Sam Houston State University, Baylor University, the University of North Texas and other schools — including his alma mater, the University of Texas at San Antonio.

Today, Cantu’s project has amassed thousands of books. Books about history, geography and math. There are dictionaries, atlases and encyclopedias, writing guides and old textbooks, biographies and self-help books.

Many have been distributed at juvenile facilities across the state. Hundreds — maybe thousands — more are in storage units and stacked up in Cantu’s Montrose home, waiting for a place to go.

The books have a chance to change lives in the detention centers, said Chip Walters, who retired this year as a senior director at the Texas Juvenile Justice Department.

He was a correctional officer at Giddings State School, a youth detention facility, when Cantu first started speaking to young inmates.

“People want to donate ‘Harry Potter’ and stuff for those guys — and they need that, too,” Walters said.

But the instructional nonfiction books Cantu is providing are different, he said.

More than a distraction or an escape, they can be “a tool for someone who sincerely wants to make a change and wants to help themselves make that change.”

Like other teens in the juvenile system, Cantu had to present a correctional plan before he was released — an outline for what he planned to do after his release.

He earned a GED while serving time, but he had plans to go to college, start a nonprofit and, at least then, he wanted to go into the fashion industry.

“It sounds good and it sounds ideal,” Cantu said. “But a lot of youth don’t follow that plan because, once they’re released, it’s not even something they can imagine. How do I start? Where do I start? Who can I connect with? None of those things are possible.”

When he was released in 2009, Cantu said, he stumbled. He wanted to go to school, study fashion and start a clothing line. But he didn’t have a clue how to enroll in college, much less how to pay for it.

“Once I was released, I jumped on the internet and started trying to figure things out,” Cantu said.

He used Google to find out about college applications and financial aid, and found his way to a community college. He earned an associate degree there before moving on to UTSA for a bachelor’s degree.

Along the way, Cantu created a brand called “Respect Women” and began to sell T-shirts. He founded a nonprofit, Position of Power, to help fix the poverty-prison cycle.

He figured everything out through “trial and error,” Cantu said. Now he’s mentoring young offenders to help them set career goals and learn how to reach those goals.

“I just give that testimony to these youth a lot,” Cantu said. “It’s going to be hard. It’ll take a while. But the difference is, I made those mistakes and figured it out for you, in a sense.”

When he was in detention, Cantu said he heard motivational speeches from people who didn’t offer more than words and a short visit.

“That’s what disappointed me,” he said. “Somebody from the church program would come on a Sunday and give words of encouragement, and I’d never see them again.”

Cantu didn’t want to be that guy.

So he’s set up a plan to keep correspondence with the teens who are behind bars.

“We follow up with a pen pal system: ‘Here’s my information.’ … We can talk back and forth. And all your personal stress, you can vent that to us.”

When he can’t handle all the correspondence, Cantu calls on volunteers from Alpha Phi Alpha, his fraternity, to assist.

Richard Azagidi started helping Cantu a few months ago. A fellow Alpha Phi Alpha member, he’d graduated from the University of Houston and wanted to continue doing community-volunteer work.

He’d also heard about Cantu’s book project.

“Then one day I read up on his past and saw everything he did,” Azagidi said. “I was very inspired.”

Azagidi has seen Cantu work with kids directly, he said — including one young man who had just been released from juvie.

“He took him out to get him some food and professional clothes, talked to him about career plans,” Azagidi said.

“He deserves so much credit for the things he’s done,” said Walters, the retired juvenile justice director. “This is a young man who’s really stepped forward and made some significant changes in his life.”

Cantu’s project has amassed thousands of books. Books about history, geography and math.