GREATER DEMAND FOR A LITTLE LAMB

Hill Country ranchers also find it’s a hot market for goats

By Lynn Brezosky STAFF WRITER

COMFORT — Blame it on the canned mutton.

During World War II, soldiers were given rations of gnarly old sheep meat that turned a whole generation and their offspring off to eating anything that once said, “bahh.”

That and other factors, such as the Clinton-era removal of wool and mohair price supports from the farm bill and a general move away from agriculture, have shrunk the nation’s sheep and goat industry to a fraction of what it once was.

Just in the Edwards Plateau area, there were once some 6 million angora goats. There are now estimated to be to less than 80,000 in the entire United States. As far as sheep, the nation produces less than 1 percent of the global wool supply.

But things appear to be changing for the American sheep and goat industry, and it’s good news for Texas, which ranks top in production of both.

For one thing, wool is back in fashion with outdoor retailers. There’s a good chance some Texas wool went into the ceremonial Winter Olympic hats and sweaters designed by Polo Ralph Lauren.

Sheepskin’s all the rage for stylish rap stars and is in high demand in cold places like Russia and northern China.

At the Nugget International plant, tucked into an industrial area of San Antonio, skins are destined to end up as Rolls Royce floor mats, commercial flight deck padding, Western saddles and jackets that retail for nearly $2,000 at a specialty shop in Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

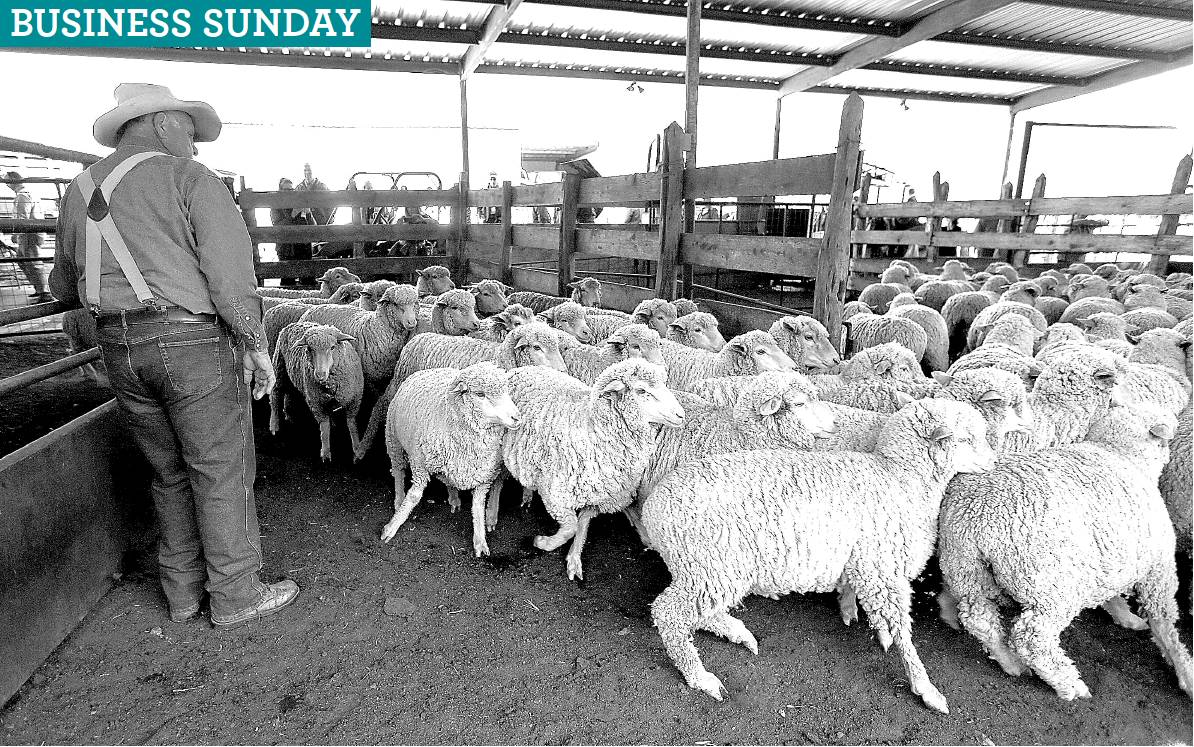

The East Coast ethnic market of Muslims, Greeks and Africans has been revolutionizing Texas sheep production. The nation’s largest sheep and goat auction, in San Angelo, sells almost exclusively to “nontraditional” buyers in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

As for traditional markets, there’s that whole “foodie” phenomenon going on with younger generations who are eager to try new things. So while the average American still eats less than a pound of lamb a year, and the nation as a whole eats a negligible amount of goat, producers are having no trouble finding markets.

“We’re not producing enough lamb to meet the demand that we have,” said Brant Miller, a Maine sheep producer who was part of the American Sheep Industry’s recent convention in San Antonio.

The American Lamb Board, an industry group, has been seizing on the opportunity to market to a burgeoning fan base.

“We like to say we’re not your grandfather’s mutton,” said Megan Wortman of the American Lamb Board. “The genetics and feeding and production practices have improved by leaps and bounds.”

“All the food trends are aligning so perfectly for us,” Wort-man added. “We’re obviously excited about the millennial younger generation, they don’t have the biases toward lamb that we’ve been sort of battling. They’re super interested in new, adventurous flavors. They’ve traveled. They’ve been exposed to eating out a lot and they’re willing to pay a premium for interesting, high quality food.”

As it stands, more than half of what Americans find in their supermarket meat case comes from Australia and New Zealand.

With the market clearly there, the industry is looking for ways to increase production.

“Almost 2 pounds of every 3 pounds of lamb consumed in the United States is imported,” said Reid Redden, a sheep and goat specialist with Texas A&M University AgriLife Extension. “Our goal is just to be able to help people improve and raise a larger crop.”

A&M recently won a grant from the American Sheep Industry Association to use sonogram technology to increase the number of ewes, or female sheep, giving birth to twins. It’s a method that’s relatively new to Texas, where thanks to the warm climate sheep tend to stay out on the range rather than being brought indoors during lambing time. The sonograms allow ranchers to identify the ewes more likely to birth twins so they can be electronically tagged and put out to separate pastures for breeding.

In just the first two years of the project, the number of ewes having twins at the 130-year-old Hillingdon Ranch in Comfort increased to 60 percent from 50 percent.

A mix of cattle, sheep and goats graze the Hillingdon Ranch’s more than 13,000 acres, which ranch patriarch Robin Giles says improves the land and provides for a buffer against swings in one or more of the three markets.

It’s been a challenge for the Giles family, who over the generations have had to grapple with predators — in 1970 they lost 450 head of sheep in three months to coyotes — and parasites. By culling affected animals, they’ve built up a herd with a strong internal resistance.

As their neighbors leave the business, they’ve been able to negotiate leases that allow them to expand their pastures while allowing the owners to enjoy the land for deer hunting and other recreational uses.

The Giles specialize in traditional lamb and sheep wool, and hold onto their goats’ mohair for the occasional spikes in demand. With the demise of price supports in the 1990s, the U.S. mohair industry fell apart. The mohair is now sent to South Africa for processing.

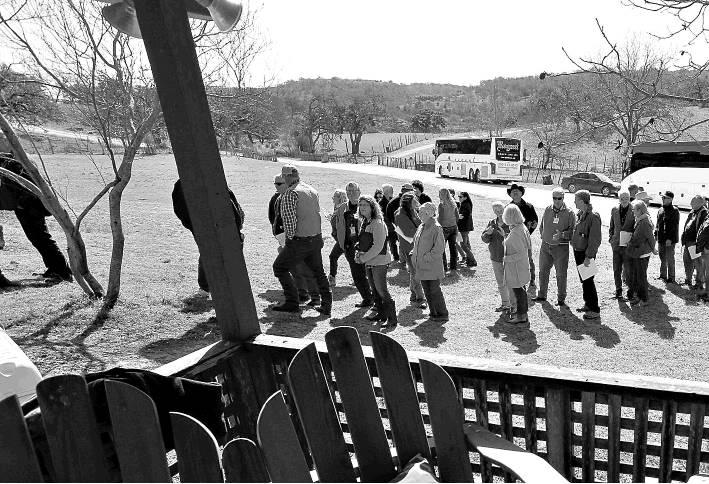

“Wherever there is affluence in the world you’ll see heavy use of mohair,” Robin Giles told national and international sheep producers during a Jan. 31 ranch tour. “For a while Japan was it, those crazy Japanese, if it wasn’t a $15,000 suit; they didn’t want to wear it, so they were our big mohair market for just a little while. Now it’s China.”

But elsewhere in Texas, producers have been turning to “hair sheep,” such as Dorper sheep, raised not for their fluffy wool but for their smaller frame that appeals to the ethnic buyer.

The Texas wool industry predates the state itself, as the Spanish brought sheep across the Atlantic to graze on their earliest settlements. Capt. Richard King devoted a large part of his ranch to raising some 30,000 head of improved Merino. It tided the ranch over during a depression in the beef business in the 1870s. Famed ranch banker Charles Schreiner wouldn’t loan unless the ranch had sheep, as sheep always paid the bills.

In the 1940s, at the height of the U.S. sheep industry, there were about 56 million sheep in the U.S. There are now about 5.3 million, with 800,000 of those in Texas.

Drought, predation, labor issues, the loss of farm bill supports, an aging ranching population and large land buys for nonranching use have all contributed to the decline, said Benny Cox, who runs the sheep and goat auction at San Angelo.

“The goat market, it got crazy with all these different ethnicities coming into our market and buying things,” Cox said. “In 1995, I thought, “Oh my Lord, we sold a lot of goats. So I wrote it down and we sold 86,000. The next year we sold 165,000. In 1998, we sold over 200,000.”

The hair sheep were proving a good investment thanks to that ethnic demand and the ewes quick recovery after lambing.

“They’ll breed back with their baby still suckling them,” Cox said. “You can’t get a wool sheep to do that.”

The last year the San Angelo auction sold more wool sheep than hair sheep was 2010, Cox said.

The Hillingdon Ranch is a picturesque place, with a ranch house that is generations old and a pavilion that has hosted family weddings with whole legs of lamb slow-roasting over an open fire.

“The temptation is to sell it of course,” said Grant Giles, Robin’s son and father of what he hopes will be part of the next generation of ranching. “Once it gets sold and it goes into a housing development, it doesn’t return back into this state. It’s a one-way street ... What are you going to invest the money in that’s going to be as special for your children and your grandchildren?” lbrezosky@express-news.net