Immigrants aiming to serve stymied

Rule bans Guard, Reserve from enlisting noncitizens

By Jason Buch STAFF WRITER

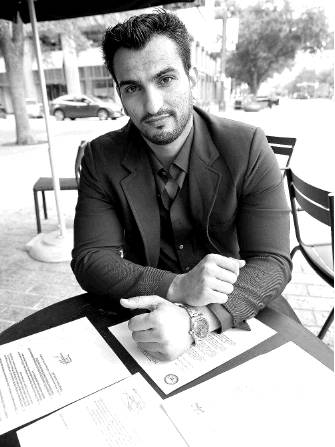

AUSTIN — The day after Mohanad Albdairi began his enlistment in the Army Reserve, recruiters called him back with bad news: Immigrants, even those here legally, can no longer join the Reserve force.

Albdairi, 32, an Iraqi immigrant, had served in the New Iraqi Army, formed with the support of the U.S. after occupying the country, then worked as an interpreter for U.S. forces until threats by militants forced him to flee the country.

He underwent extensive background checks to get his special immigrant visa but was told he’s a security risk who can’t join the Army Reserve.

The October rule change temporarily halting National Guard and Reserve recruitment of noncitizens is the latest barrier to immigrants joining the military, critics of the new policies said.

“That’s the first time in American history that green card holders have been barred from joining the military,” said Margaret Stock, a retired lieutenant colonel in the Army and an immigration lawyer in Alaska. “It’s unprecedented, to be barred openly from joining the Guard and Reserve.”

The Department of Defense announced this fall that foreign enlistees in the armed forces will have longer wait times to become citizens, and it continued suspension of a program that allowed visa holders with special skills to join the military.

Most enlistees must have lawful permanent residence, known colloquially as a green card. Under the George W. Bush administration, Stock helped develop a program to allow visa holders who hadn’t obtained or weren’t eligible for green cards but who had certain language skills and medical training to join the military.

The Military Accessions Vital to National Interest Program, known as MAVNI, was created to fill much-needed positions in the military. It was suspended last year under then-President Barack Obama. Stock blamed its halt on what she called “anti-immigrant sentiment that appears to be rampant and has infected the Pentagon.”

Anthony M. Kurta, a retired rear admiral who at the time was acting undersecretary at the Pentagon, signed three memos in October that critics said erect hurdles for immigrants to enlist. Kurta was with the office last year when the MAVNI program was suspended, Stock said, and is President Donald Trump’s nominee for its deputy undersecretary.

Along with continuing the suspension of MAVNI, Kurta’s memos require noncitizens to undergo a background check, which can take months, before they can report for basic training.

Kurta’s memos didn’t ban joining the Guard and Reserve outright, but neither the Guard nor Reserve have a way of running background checks before enlistment takes place, so they had to halt all recruitment of green card holders.

Albdairi has a green card, but he can’t join the Reserve under the new policy. The Defense Department is in the process of creating a system to run background checks on Guard and Reserve enlistees before they begin training, said Army Maj. Dave Eastburn, a Pentagon spokesman. The new rule was created because immigrants were completing basic training before their background checks were completed, Eastburn said.

“It actually helps the service member in the long run, but it potentially could prolong the process,” he said. “By completing the background check prior to service member shipping … there’s no potential holdup at the end of basic training due to the background check not being done.”

The memos also require green card holders to serve 180 days before they can begin the citizenship naturalization process, adding significant delays to lawful permanent residents going through the military’s expedited citizenship program

Another recruiting tool most recently used after the 9/11 terrorist attacks expedited naturalization allowed enlistees to begin a shortened citizenship process after one day of service. Lawful permanent residents are limited in what duties they can perform for the military, and many who enrolled in the expedited process and took part in U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services’ Naturalization at Basic Training Initiative became citizens upon graduation.

“It is in the national interest to complete the security investigation before we grant someone honorable service, particularly in the case where that characterization is considered in an application for citizenship,” Stephanie Miller, the Defense Department’s director of accessions, told the Pentagon’s in-house news service.

The delays effectively serve as a barrier for immigrants to enlist, Stock said. The wait times are onerous and will drive away qualified foreign-born recruits, she said.

“This doesn’t help security at all,” Stock said. “It makes things worse. It means a lower-quality workforce in the military. And it gives away the United States’ largest home-court advantage. We’ve always welcomed immigrants. We’ve won wars because we had them in the ranks.”

The U.S. population is 13.5 percent foreign-born, lower than it was at the start of the 20th century but up from historical lows 40 years ago.

“They’re basically saying 13.5 percent of the population is off-limits,” Stock said. “That means they have to give a lot more waivers for depression … pot use, drug use, criminal (convictions). That’s what they’re doing. They’re letting more low-quality native (-born) people into the military right now than they would have to let in if they were recruiting immigrants.”

Of the 1.98 million people who joined the armed forces between 2000 and 2010, only 3.8 percent were noncitizens, according to a 2013 thesis by students at the Naval Postgraduate School. A 2011 study conducted for the Defense Department by CNA Analysis and Solutions found that immigrants have a lower attrition rate in the armed forces and represented a growing share of the 18-29 population targeted for recruitment.

The study also found that “noncitizens who are eligible to enlist may possess language and cultural skills that are useful in theater, or medical and technical skills that can be used to fill high-demand, low-density occupations.”

Eastburn rejected Stock’s assertion that the new policies will result in a personnel shortfall.

“There’s no shortage and there’s no need to issue waivers to anyone who wouldn’t otherwise be eligible to serve,” East-burn said.

Albdairi, who’s studying criminal justice at Austin Community College, said he saw enlisting in the Army Reserve as a way to give back to a country that had welcomed him, and also to help his family. He acknowledges that he’s struggled to find gainful employment and thought serving in the Reserve would be a way to supplement his income.

Active duty isn’t an option, he said, because his wife doesn’t speak English and needs his help caring for their two children and still suffers from the trauma of seeing her uncle gunned down in front of her, retribution by militia members for the help Albdairi gave the U.S. He still blames himself for the man’s death.

“I decided to join the Army because part of me appreciates this country for my family’s safety,” he said. “And part of me, to be honest, I’m tired of these jobs. So I’m thinking of doing something part time for the Army and serve this country. Because my life is over in Iraq. This is my country now.”

Albdairi was enrolled in college when the U.S. invaded Iraq in 2003. The next year he joined the New Iraqi Army and served until 2006. After leaving the military, he worked as an interpreter for U.S. forces until he got his visa six years later. That included not just translating, but explaining Iraqi culture, right down to naming conventions, which U.S. military personnel didn’t always understand.

“I always enjoyed it because I want to help people,” Albdairi said of his time as an interpreter. “I know both sides, my people and the U.S. Army. I’m in the middle.”

After he’d been on the job about a year, Albdairi said, militias in Iraq began targeting interpreters and their families. He had to move his family out of Baghdad and he couldn’t leave the U.S.-controlled Green Zone.

In 2008, he applied for a special immigrant visa, which allows interpreters in Iraq and Afghanistan to come to the U.S., but it took four more years before he could come here and get a green card.

Albdairi spent a few months in San Antonio before moving to Austin at a friend’s suggestion. He’s washed dishes, worked as a delivery driver and as a driver for ride-hailing apps. Albdairi said he’s disappointed he couldn’t join the Army Reserve and that he’d have to wait a year for background checks if he wanted to go active duty.

“I spent three years with the Iraqi Army and five years with the U.S. military,” he said. “It’s in my blood. I want to do something to help this country.”

Stock called Albdairi “a perfect example of why this new policy makes absolutely no sense.” The background checks he underwent to serve as an interpreter and come to the country on the special immigrant visa should have assuaged any concerns that he’s a security risk, she said.

“If they can’t get a guy like him into the military, you know what they have to use?” she asked. “Unvetted foreign contractors at great expense to the U.S. taxpayer.” jbuch@express-news.net