Brackenridge has seen lots of dreams in 100 years

By Alia Malik STAFF WRITER

When George W. Bracken-ridge donated land on what was then the south side of San Antonio for an educational institution, he included $40,000 for a building and $5,000 for a library.

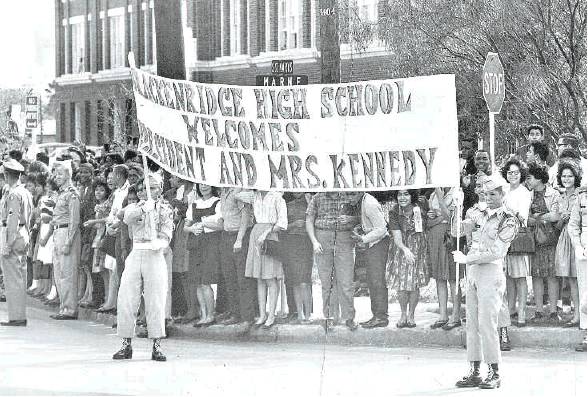

Those were 1916 dollars and the red brick, three-story building ended up costing more than $300,000. Exactly a century ago today, San Antonio’s first academic high school, named for its patron, was dedicated. The school has since been completely rebuilt on the same land, now part of the trendy inner-city King William neighborhood.

Students, employees and alumni today will celebrate that centennial, a sometimes tumultuous history shaped by the city’s racial segregation, the national legal challenge to integrate public education — and a fierce fight over the school’s name along the way.

“Anyone can dream, but making dreams come true is a science,” the San Antonio Express wrote in February 1917 about the new school. “The minds of many must contribute if ‘air castles’ are to be changed into material things of beauty, of actual concrete and rock.”

Brackenridge’s first cohort came from San Antonio High School, a vocational school that eventually became Fox Tech. But they continued to attend classes at San Antonio High until fall 1917, when Bracken-ridge opened, so the Brackenridge Alumni Association has been celebrating the centennial for more than a year, its historian Dianna Buxkemper, 71, said.

A free public school for black students had operated since the late 1860s, according to the Texas Historical Commission, replaced in 1932 by Phillis Wheatley High School on the East Side. Other high schools in the San Antonio Independent School District had opened by 1939, the year Lanier High beat Brackenridge for the city basketball championship.

At the end of the game, a Brackenridge fan punched a Lanier star player, setting off a riot between Latinos and Anglos, according to Ignacio Garcia’s book, “When Mexicans Could Play Ball.”

Desegregation closed Wheatley High in 1970, and two years later Emerson Middle School moved to its building, said Leslie Price, SAISD spokeswoman. Brackenridge students, meanwhile, attended classes in shifts at Fox Tech while their building was demolished and rebuilt, according to SAISD.

Brackenridge reopened in 1974 with the Wheatley High name, an attempt to appease East Side community members who thought white students should have been bussed to Wheatley. The switch infuriated Brackenridge alumni, who fought to keep the eagle as the school’s mascot over the Wheatley lion.

“Someone suggested calling the new team the Griffins, a mythological creature with a body of a Lion and the head and wings of an Eagle,” wrote Harry Page of the Express-News. The eagle eventually won out.

Buxkemper came to the school as a guidance counselor in 1980, when it still was named Wheatley. Seven years later, alumni of Brackenridge High and the former Wheatley High on the East Side asked the SA-ISD board to restore the old names to their respective buildings, setting off a battle royal documented in Express-News archives.

“Most of the students were sons and daughters of Brack graduates,” Buxkemper noted, so a student survey chose Brackenridge by a 2-1 ratio. Some told the Express-News they thought the name change would attract more scholarship money from Brackenridge alumni.

Members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People called the proposal racist and said they’d accept nothing less than a high school named for Wheatley, the first published African-American poet. About 250 people packed the Jan. 25, 1988, school board meeting, some accusing teachers and coaches of campaigning for the name change despite a board-ordered moratorium on the debate during exam week.

The board’s vote to return the Brackenridge name was divided, with its only black trustee dissenting. It brought both cheers and tears, the Express-News reported.

Buxkemper retired in 2002, when it enrolled about 1,750 students and was predominantly Hispanic, as it is now. In the early 1980s, it was the only high school in SAISD that taught calculus and had a multilingual magnet program, fed by similar programs at Davis and Tafolla middle schools, she said.

Famous alumni include Robert Cade, leader of the research team that developed the formula for Gatorade, who graduated in 1945; veteran broadcast journalist John Quiñones, host of ABC’s “What Would You Do?”; local TV journalists and brothers Fred and Rick Lozano; pro football players Warren McVea and Sam Hurd — who both have faced legal troubles and incarceration, and Ramon Richards, a current Oklahoma State University player who recently intercepted a pass to defeat the University of Texas.

Brackenridge now has an early college program, in partnership with St. Philip’s College. It is getting a $50 million share of the SAISD bond that passed last year, for improvements that include a renovated dance and pep room, a re-coated track and new fencing for tennis courts.

“I think it’s a big deal that the school still exists 100 years later, and we are still promoting education the way Mr. Brackenridge did,” Buxkemper said.

Brackenridge, a director of the Express Publishing Company, was the first SAISD board president and served 25 years on the University of Texas Board of Regents. Even before his gift to help build the school that bears his name, he also had donated money for schools for African-American and Mexican-American children and helped his sister found Texas Woman’s University, Buxkemper said.

She thinks it was Bracken-ridge’s ghost that twice interrupted her association’s 100th scholarship presentation at his former home at the University of the Incarnate Word campus last May.

The doorbell rang and no one was there, she said, so she told the gathering that George Brackenridge and his sister Eleanor had come to the party.

“I really believe that, but my students think I’m crazy,” Buxkemper said. amalik@express-news.net