TROUBLE BREWING

They’d rather talk about beer, but wastewater is a hot topic for local breweries

By Alex Kuffner | Journal Staff Writer

NEWPORT

When Brent Ryan and three of his college buddies opened Rhode Island’s first microbrewery in 1999, they didn’t give any thought to all the used water full of yeast, sugars and bits of hops that they’d be emptying into the Aquidneck Island sewer system, and nobody asked them about it.

Two decades later, it can seem like wastewater is all anyone’s talking about in the beer world these days.

Ryan, president of Newport Craft Brewing & Distilling, couldn’t get away from the subject last month in New Hampshire, at the regional meeting of the Master Brewers Association of the Americas, a leading industry group.

“I would have loved to have talked about new hops, but what we had to talk about was wastewater treatment,” he said.

Ryan can’t even escape it at his own place of business, an industrial warehouse and taproom off Coddington Highway that was built in 2010. He ducked into his office on a recent afternoon and came out with the current issue of The New Brewer, a trade publication.

The issue is devoted to sustainability, and there on page 61 is an article with the headline “Wastewater: It’s Time to Have ‘the Conversation.’”

The time has certainly come in Rhode Island.

The number of breweries in the state has tripled in just four years, adding up to an influx of high-nutrient wastewater that cities and towns have never had to clean up before and hadn’t contemplated ever having to deal with.

Throw in inconsistent wastewater permitting rules from one community to the next, and it’s no surprise that confusion has sometimes followed — most notably in the case of a pair of breweries in Warwick.

“A lot of it just comes down to awareness,” said Terry Gray, deputy director of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. “Sometimes when you get faced with something unexpected, it escalates the conflict pretty quickly.”

All beer brewing follows a basic process that starts when a milled grain, typically malted barley, is mixed with hot water in a large vessel called a mash tun. As the mixture steeps, enzymes convert starches in the grain to sugars, creating a sticky liquid known as wort. The wort is drained out and poured into a brew kettle, where it’s boiled with hops and other flavors.

The flavored wort is then cooled down, filtered and moved to a fermentation tank, where yeast is added to turn the sugars into alcohol, and the liquid starts to become beer. When complete, the beer may be moved to a conditioning tank to smooth out the flavors. It may be filtered again before being packaged for consumption.

Waste can be generated every step of the way. There’s the spent grain left in the mash tun; the proteins and other solids known as trub that may be filtered out of the boiled wort; waste wort liquor; yeast; sugar and more trub that settles at the bottom of the fermentation tank; beer spilled during packaging; and water, often mixed with caustic solutions or disinfectants, used for cleaning bottles, cans, kegs and equipment.

Used grain is easily collected and makes great animal feed, so farmers are always looking to get some, and brewers are happy to give it away.

Trub, dead yeast and other organic solids also have their uses: as fertilizer, composting additive or soil application, or as feedstock for anaerobic digesters that produce biogas to generate electricity. But because these materials are produced at various steps along the process, they’re harder to gather up. While separating out grain is standard practice at breweries, side-streaming these other materials, which is sometimes known as pre-treatment, isn’t done universally.

And then, of course, there’s the waste liquid that has to be dealt with. The typical brewery uses about seven barrels of water for every barrel of beer produced, according to the Brewers Association. (A barrel equals 31 gallons.) After losses due to evaporation, about 70% of the water breweries use is discharged as effluent.

It’s not really the amount of wastewater that’s problematic. It’s all the stuff mixed into it, especially if there’s no side-streaming. Using one standard measure, known as biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), a typical microbrewery can discharge wastewater with an organic load equal to 100 or more homes.

Such concentrations aren’t hazardous, but they can put a strain on a municipal treatment plant, which may have to step up aeration to produce more bacteria to break down the material. That takes more power and costs money.

At high enough doses, brewery wastewater can even kill these microorganisms. And if the effluent gets into waterways untreated, it can fuel algae blooms that, in the most extreme cases, create the low-oxygen conditions that cause fish kills.

If there’s a worst-case scenario, it happened in Vermont, which has more breweries per capita than any other state and is home to Heady Topper, a near-mythical beer that some consider the best in the world. In the summer of 2018, the city of Burlington was forced to close public beaches on Lake Champlain because of high bacteria counts after its treatment plant was overwhelmed by intense rains and large discharges from food and drink producers.

Operators of the plant blamed the contamination in part on breweries that, according to the TV station WCAX, account for only 1% of Burlington’s wastewater flows but 15% to 30% of its biological loads. Yeast and other material from breweries had upset the mix of nutrients that the facility’s bacteria feeds on, they said.

“The plant has a bellyache,” wastewater facilities manager Matt Dow told reporters in the wake of the incident, according to the newspaper Seven Days.

Everything changed for beer production in Rhode Island on July 16, 2013. That was the day then-Gov. Lincoln Chafee enacted an amendment to state law that allowed breweries to offer take-home samples of up to 72 ounces per person as part of tastings or tours.

Until that point, businesses like Grey Sail Brewing, in Westerly; Foolproof Brewing, in Pawtucket; and Ryan’s company, which was then known as Newport Storm, weren’t allowed to sell packaged products on site, making a key profit stream unavailable to them.

“I didn’t realize it was going to be such a big deal,” said Ryan, who lobbied for the change for five years before it passed. “It allowed small guys to make a profit.”

The change had been years in the making and represented a chip in the walls erected after Prohibition was repealed that separate the state’s beer manufacturers from alcohol wholesalers and distributors. Another came in 2016, when the cap on purchases was raised. And one more followed last year, when it was adjusted again.

From five breweries in the state in 2013, the number doubled to 10 in 2016. In October, there were 27. Now there are 31 and at least two more are in the planning stages, according to the Rhode Island Brewers Guild, which represents the industry in the state.

“It seems like every time you turn around, another new brewery has opened,” said Gary Richardson, executive director of the guild.

There’s still plenty of room for growth. Of the 595,000 barrels of beer distributed in Rhode Island in 2017, only 26,000 were produced in the state, according to the DEM. That’s the lowest percentage of any of the New England states. And while Vermont has 13.5 breweries per 100,000 adults, Rhode Island has only 3.2, according to the Brewers Association.

“It’s an industry that’s prime for expansion,” Joseph Habarek, supervising sanitation engineer at the DEM, said at a wastewater workshop for brewers last fall.

But the budding industry is butting up against an established network of municipal wastewater treatment plants, many of which are decades old and were generally designed to deal with household effluent and have permitting rules founded on that premise.

Wastewater treatment is regulated on the federal level, but enforcement is generally left to state authorities. While the DEM is the enforcement agency in Rhode Island, it delegates permitting in most cases to cities and towns.

That has led to a dizzying array of policies for managing wastewater inputs that differ from place to place, in part because of the distinct capabilities of individual plants, the types of water bodies they empty into, and the demands of other users.

Communities generally fall into two camps when it comes to the key question of regulating biological loads: those that cap concentrations of BOD that flows into their system at any given moment and those that set a limit on the total amount of BOD that comes in over the course of a 24-hour period. (BOD quantifies the amount of dissolved oxygen that bacteria need to break down organic matter.)

Bristol, for instance, allows users to discharge up to 4,000 milligrams of BOD per liter, while Burrillville caps the amount at 300. East Greenwich allows for higher concentrations but charges an additional fee.

Meanwhile, Cranston sets a daily total of 25 pounds per day. Newport allows 200 pounds in the same amount of time.

As for East Providence and Westerly, they have no set restrictions.

Then there are regulations governing insoluble material, which falls under a category called total suspended solids (TSS). Again, the rule in one community may be wildly different from its neighbor.

Factor in guidelines on pH or temperature — which one system may have and another may not — and it’s no wonder that Gray says that brewers have no choice but to educate themselves on their local wastewater bureaucracy.

“We’ve been trying to get the word out to avoid a crisis,” he said.

Whether it was a full-blown crisis or not, things certainly came to a head when Proclamation Ale decided to move to Warwick.

Founded in South Kingstown in 2014, the brewery attracted a lot of buzz — founder Dave Witham was featured four years ago on the cover of BeerAdvocate magazine (a national publication that has since shut down) — and the company needed bigger digs.

Proclamation settled on 15,000 square feet in an industrial warehouse off Kilvert Street that would allow it to expand production sixfold, and contacted the Warwick Sewer Authority in early 2017 to find out about wastewater requirements. When the authority asked Proclamation what sort of pre-treatment it does, the company couldn’t answer, according to the authority.

The reason: in South Kingstown, Proclamation never had to worry about separating out any organic waste beyond its spent grain. The loads from what was to that point a smaller brewery simply weren’t an issue for the town’s wastewater system. Warwick, on the other hand, has strict controls because it releases its treated water into the Pawtuxet River, said Earl Bond, director of the authority.

The authority visited Proclamation’s brewery in South Kingstown and collected samples from the mash tun and fermenter to test for BOD. When the results came back, the levels were through the roof.

So the authority made a list of requirements that Proclamation had to meet to qualify for a discharge permit. The company would have to side-stream as much waste as possible, install a pH adjustment system, and invest in flow-metering equipment and wastewater storage so that high-strength effluent could be slowly released into the city’s system. The latter measure was aimed at preventing a “slug” of wastewater with lots of nutrients in it from entering the treatment plant and throwing it off-balance.

When the new brewery opened in December 2017, not all of the controls were in place. It took several months, but the brewery was eventually brought into compliance. Witham says the cost of the pretreatment systems and consulting fees probably reached six figures.

“Nobody knew what they were getting into,” he said.

Gray, who had a hand in resolving the dispute, described Proclamation’s situation as “ground zero” for the problems surrounding brewery wastewater.

While Proclamation was in the midst of its troubles, a startup called Apponaug Brewing began the process to get a wastewater permit for a brewpub in the old Pontiac Mill on Knight Street. Apponaug’s brewery would be much smaller than Proclamation’s — 500 barrels a year versus 6,000 — but similar concerns about effluent arose.

Justin Tisdale, head brewer at Apponaug and a veteran of Foolproof Brewing, had an inkling of what to expect after talking to Witham and others at Proclamation, but he was still surprised by the scrutiny from the authority, which also required the purchase of thousands of dollars of new equipment, monthly testing and, for a while, weekly inspections.

It wasn’t just the financial investment that was a burden, he said. There has also been a huge commitment of time to understand the city’s regulations and work with the authority.

“I used to joke that I work full time in wastewater treatment, and I’m a part-time brewer,” said Tisdale, who is president of the state brewers guild.

The issues that arose in Warwick aren’t so different from those that have come up in Burlington and elsewhere in Vermont, or, for that matter, in communities in Massachusetts and other states with more mature craft-brewing scenes.

So Gray decided to follow the lead of groups in those states and try to foster better relations between brewers and wastewater treatment operators.

“We started to see that there were two education needs here,” he said. “One was to educate treatment operators on the treatment needs of different-size breweries. And the other was to educate brewers on treatment systems.”

First came a meeting with treatment operators in the spring, and then the workshop in October for brewers. Habarek, the DEM engineer, opened the latter session with a reference to Warwick. He didn’t need to go into details. Everyone in the state’s tight-knit brewing community knows the story.

“What happened there really opened our eyes,” Habarek said.

He emphasized that every treatment plant has a finite capacity to handle effluent, and that the wastewater they release can “cause impacts if nobody’s paying attention.”

As the meeting progressed, brewers complained about testing protocols. One reason why BOD levels at Proclamation and other breweries have tested so high may have been because samples were taken from the bottom of fermenters, where organic material settles and concentrates. The numbers aren’t reflective of the effluent discharged at most times of the day, the brewers said.

They also questioned the effectiveness of regulating BOD concentrations at all, saying that such restrictions only encourage breweries to dilute their wastewater by mixing it with clean water. That means amping up their water usage when they know they should be doing as much as they can to conserve.

The fairer option, they argued, is setting maximum daily loads, which works better for breweries whose BOD concentrations and wastewater flows can fluctuate by the hour and the day, depending on whether they’re mashing, fermenting or cleaning.

It’s what the DEM is now recommending to municipal treatment systems. And it’s what the Warwick Sewer Authority ended up doing last year.

The authority calculated the total treatment capacity for BOD at its plant, subtracted out what other users in the system require, and determined that it could more than meet the needs of the city’s two breweries. It set Proclamation’s allowance at 800 pounds of material a day and Apponaug’s at 300 pounds — and still has the ability to treat another 4,000 pounds.

Bond says the authority worked hard to balance Warwick’s business climate with environmental safeguards and that there have been no problems at the city’s treatment plant caused by the breweries. Tisdale and Witham both also say that the issues have been settled and that things are going well now.

But Richardson, the director of the brewers guild, warned that if a smaller brewery or one on weaker footing encountered the same problems, it could have gone out of business.

A decade ago, as concerns mounted about its wastewater discharges, Magic Hat, a nationally known brewery in Vermont, built its own anaerobic digester to convert spent hops, yeast and grain into energy.

Organic material that would have gone down the drain to be treated by the South Burlington wastewater plant was instead used to power the brewery. By taking care of the nutrients in its effluent, Magic Hat was able to double capacity.

Other beer-makers have followed suit: Dogfish Head in Delaware, Kona Brewing in Hawaii and Saranac Brewery in New York.

Meanwhile, The Alchemist, the Vermont brewer of Heady Topper, pre-treats so aggressively at one of its locations that it has reduced organic loads to less than those of a single household. And Stone Brewing, in California, has gone so far as reclaiming its wastewater to make beer.

While Magic Hat makes 175,000 barrels of beer annually, the average Rhode Island brewery, according to the state guild, produces only 1,000. Even the bigger breweries, such as Grey Sail and Whalers, aren’t large enough to afford a digester or the most advanced pretreatment systems.

But a digester recently opened near the Central Landfill in Johnston and the state brewers guild is hoping to work out a deal with operator Orbit Energy to deliver brewery waste there. Gray has even suggested the possibility of breweries in the state banding together to build their own digester.

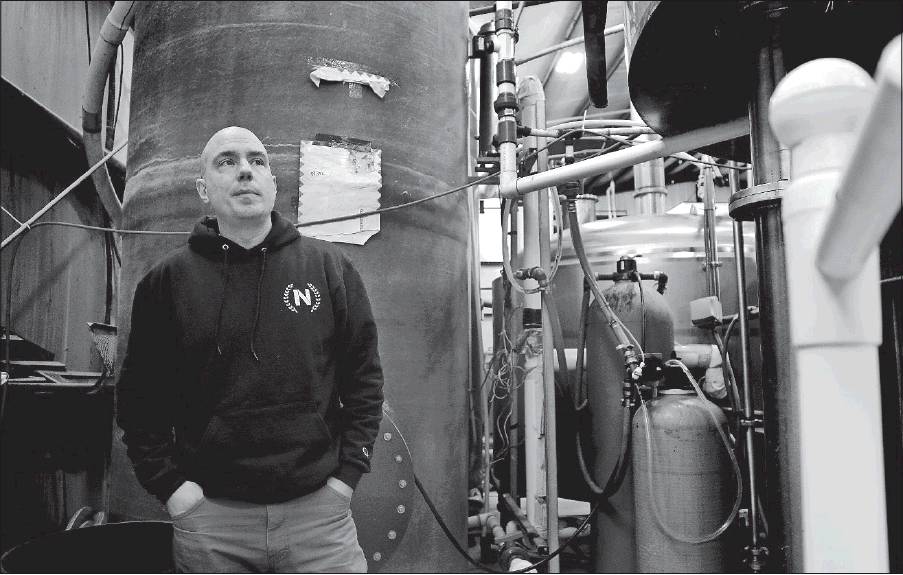

In the meantime, Rhode Island’s brewers are doing what they can to reduce the material in their wastewater. A farmer in Portsmouth picks up Newport Craft’s spent grain twice a week to give to his cows. He pays nothing and it saves the brewery the cost of having the material hauled away.

The brewery also channels wastewater from its kettle, fermenter and other equipment to a settling tank that gets pumped out for separate disposal.

“There are ways to manage this reasonably,” Ryan, a past president of the brewers guild, said as he explained the system. “This is the extent, really, of what you need to do.”

Apponaug and Proclamation give their spent grain to a pig farmer in Scituate who, according to Tisdale, has said he’s been able to expand his herd because of all the free food he gets. Apponaug separates out yeast and trub and mixes it with the grain. Proclamation does the same thing as Newport Craft.

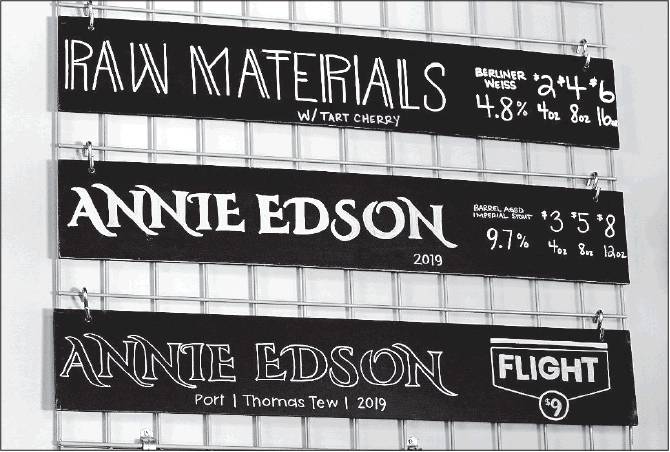

A few years ago, wastewater wasn’t something on people’s radars, Tisdale said as he showed two visitors the gleaming equipment he uses to make everything from sour ales to pilsners to IPAs in his work space overlooking the Pawtuxet River. He described those days as “the Wild West.”

He does have doubts about the actual impact that brewery wastewater can have on treatment plants. Elements of the plant failure in Burlington sound apocryphal to him. Still, he is diligent about monitoring Apponaug’s wastewater.

Asked what advice he’d give to anyone looking to open a brewery in the state, he’s unequivocal: drop everything and contact the treatment authority in your community.

“If you haven’t called them, call them right now,” he said. “If you have a time machine, go back two months and make the call.” akuffner@ providencejournal.com / (401) 277-7457