JOURNAL WATCHDOG REPORT

Sentence without end

On Friday, a summit will explore how judicial fees and fines keep ex-offenders cornered by debt

By Katie Mulvaney Journal Watchdog Team

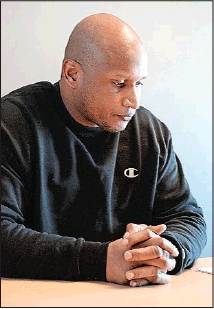

CHARLESTOWN — Life is a struggle for Walter McLean Jr.

He’s recovering from an addiction to opioids. He can’t find housing. He is unable to work due to diagnoses of bipolar disorder, PTSD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and carpal tunnel syndrome.

And he’s facing more than $3,300 in court fines and fees for criminal convictions dating back decades, many linked to his substance abuse. He pays off $20 every other month, the $10-a-month minimum payment typically accepted by the court.

“It was really stressing me out. It was screwing with my recovery. I was just so scared to miss it and end up going back to jail,” said McLean, 61.

McLean finds himself locked in a cycle that criminal-justice reform advocates say keeps low-income former offenders in poverty. Often, they are searching for jobs and housing, re-establishing relationships and managing mental illness and substance use disorders after serving prison terms.

That cycle will be the subject of a summit focused on court fines and fees hosted by the Rhode Island Public Defender and the Rhode Island Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. Set for Friday at the state Department of Health, the forum is entitled “Worth the Cost? Or Impediments to Reentry, Rehabilitation & Recovery? A Legal, Public Health & Educational Response.”

“A lot of the people they give these fines to can’t pay them,” said Anthony Thigpen, a community health worker at Rhode Island Hospital’s Center for Primary Care. A former inmate, Thigpen now helps ex-offenders transition back into the community.

“They run, and when they run, they can’t take care of themselves,” he said. They miss doctor’s appointments, let prescriptions lapse and go into hiding for fear they will be arrested on a warrant for failing to appear to make a court payment, he said.

McLean, like many former inmates, has landed back in prison over the years after missing payments. Advocates estimate that 15.5% to 18% of all prison commitments in Rhode Island are related to court debt.

Thigpen spent a night in jail in 2013 for missing a court date. He recalled being stopped by Providence police on a bench warrant one afternoon as he drove to pick up his daughter from daycare.

“They said, 'Get us some drugs or a gun,’” he said. Thigpen was incredulous. “You want me to turn someone’s life upside down over a bench warrant?”

Thigpen was held overnight. He had to arrange for someone to pick up his daughter and leave his car on the street overnight. His wife bailed him out and paid the fee the next morning. Each apprehension on a warrant adds another $125 to what an ex-offender owes.

“This is the pressure they’re putting on people: You’ve got to go back to jail or you’ve got to rat,” said Thigpen, 40, who has since paid off his court costs.

Providence police Col. Hugh T. Clements Jr. could not speak to the specifics of Thigpen’s case, but he said that when it comes to warrants, the authority rests with the courts, not police officers.

“If we run someone and they have a bench warrant, we have a responsibility to arrest. It’s not our warrant to forgive, it’s the court’s warrant. We have to hold them,” Clements said.

“We do not really discuss our methods of developing information. We certainly do not discuss who has cooperated … unless it’s mandated by the courts,” he said.

For years, McLean’s outstanding court fees remained off the courts’ radar, until his arrest in 2016 for felony shoplifting.

“They went back and found them all, but I didn’t know they were there. I was like, 'Holy mackerel, how am I going to do this?’” McLean said, estimating that he owed upwards of $5,000 from charges dating to the 1980s.

He tried to start making payments, but couldn’t manage the $30 a month the courts initially sought.

“Just crazy stuff was going on in my head. I started using drugs,” McLean said of initially learning of the debt he owed. He now estimates he's a year and a half clean.

He contemplated working under the table, although he receives disability benefits.

“'What if they find out about this?’ It was like a carnival going off in my head. I was homeless and fighting for recovery. I felt like giving up, to be honest with you,” said McLean, who stays on and off with a friend in Charlestown as he continues to look for housing. His bus trips to court in Providence to make payments and go to doctor's appointments take an hour and 10 minutes each way.

Today, McLean, a lean man with worry etched on his face, is committed to his recovery. “I’m 61," he said. "I don’t want to go that way anymore."

In total, more than $55 million in fees, costs and fines were assessed in Superior and District courts and the state Traffic Tribunal for the fiscal years starting July 1, 2016 and ending June 30, 2019, according to information provided by the Rhode Island judiciary. Of that sum, $21 million remains outstanding, the data shows.

Added to that sum are fees from years earlier, such as those McLean is trying to pay. Data provided by the courts last spring put the amount owed for 2014 and prior at $27 million, though presumably payments have reduced that amount. The vast bulk of payments go to the state’s general fund.

Fees and fines can easily mount for people encountering the state’s criminal justice system. Under state law, a person who is convicted or pleads to a misdemeanor would owe $93.50, $60 of which heads into the state’s general fund and $30 to the victims’ compensation fund. The remaining $3.50 heads to the police department or entity that brought the charge.

People convicted of felonies face fees of $270 to $450 per charge, a portion of which goes into the victims’ compensation fund. The court also imposes fines of more than $1,000 meant to punish and deter defendants for felony offenses. In addition, there are lab fees of $118 for drug convictions. If a person is convicted on multiple counts, the fees continue to add up.

Court-imposed fees and fines are a topic state leaders are grappling with nationwide, with some states enabling defendants to reduce the money owed by performing community service or doing jail time. (In Rhode Island, for each day spent in prison, offenders can shave $50 from what they owe.)

Many states have moved to offer some type of community-service option as an alternative to payment, according to the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University Law School, a nonpartisan law and public policy institute.

In 2018, Massachusetts passed criminal-justice reforms legislation with bipartisan support. The state instituted community service as an alternative to court debt — a move critics argued could keep poor defendants away from jobs needed to return them to stability. The state also raised the minimum age of criminal responsibility from 7 to 12 and changed the way in which bail, fines and fees were assessed to account for an individual's ability to pay.

OpenDoors, a nonprofit organization founded in 2003 that serves formerly incarcerated people and their families, in 2008 successfully pushed for reforms in the law governing court fees and fines to require Superior and District court judges to assess a defendant’s ability to pay. The law gives judges the discretion to waive fines and fees, but not restitution.

In practice, however, judges aren’t making those determinations, according to Nick Horton, co-executive director of OpenDoors.

“The courts have largely ignored the law, so the system has continued.… We think the 2008 reform should be enforced. People cannot afford the same amount of money. In some cases, they can’t pay anything,” Horton said.

OpenDoors and other advocacy groups are pushing to add more teeth to the law, though they do not view it as discretionary, Horton said.

“Although things are better than before, the courts are still aggressively trying to collect millions of dollars from the poorest in Rhode Island,” Horton said.

Craig N. Berke, spokesman for the state judiciary, agreed that judges are not uniformly assessing defendants’ financial status, though he did not know with what frequency it happens.

“The courts agree the use of the ability-to-pay hearings has been inconsistent. The courts are actively reviewing this situation,” Berke said, adding, “We recognize we need to tighten up this process. We are open to improving this process. We are open to working with stakeholders to address the issue.”

Like the judiciary, state Attorney General Peter F. Neronha’s office plans to be at the summit.

“In general, the attorney general is supportive of any measures that would reduce barriers to re-entry and improve equity within the criminal justice system,” spokeswoman Kristy dosReis said in an emailed statement. “We look forward to reviewing the proposed legislation and discussing with our partners in the criminal justice system, including the defense bar and the courts.”

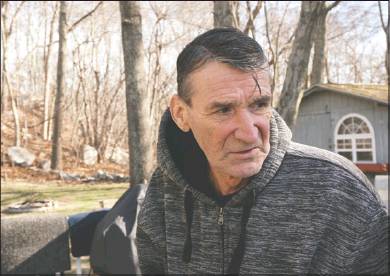

Meko Lincoln, at one time labeled by Providence police as “a one-man crime wave,” also believes he’s flying under the courts’ radar since he was released on parole in December 2018. He owes more than $6,000 for crimes that began in the early 1990s.

Now four years into his recovery from opioid-use disorder, Lincoln is working as a re-entry case manager at Amos House. He spent some 17 years in prison on convictions that ranged from drug possession to second-degree robbery to assault. He is about to file taxes for the first time in a long time, and grew discouraged after receiving notice that his return would be docked the $1,140 he owes for being on probation. He had planned to use the money to help his 27-year-old daughter.

“We’re trying to find something to eat, trying to find housing. Being a convicted felon, it’s really hard to get jobs. That’s a heavy amount of money,” Lincoln said.

“I understand we have a debt to society, but be practical, be understanding. When someone goes to prison, that is their punishment. They’ve got all these hidden punishments,” he said.

Lincoln considers himself fortunate. He has a job, a car, two daughters, grandchildren — unlike many others.

“These fines do not help people help themselves. It’s counterproductive to progress and recovery,” he said.

Horton and others hope the summit sparks creativity on the part of state leaders to relieve what they view as a burden to some of the state’s least fortunate.

“It’s very hard to get people to care about the financial rights of individual defendants, even when they are supposed to,” he said.

The summit is the second program in the John J. Hardiman Memorial Continuing Education Series. It will take place from 9:30 a.m. to 4 p.m. Friday at the state Department of Health, 3 Capitol Hill, in Providence. The program is free and open to the public, but registration is required at https://tinyurl.com/finesfeesRI kmulvane@ providencejournal.com

(401) 277-7417

On Twitter: @kmulvane