WATCHDOG TEAM

Home-based gun sales a loaded issue

A state senator deals guns from his Providence home. Here’s why it’s legal — and why it could be a problem for the city

By Brian Amaral Journal Watchdog Team

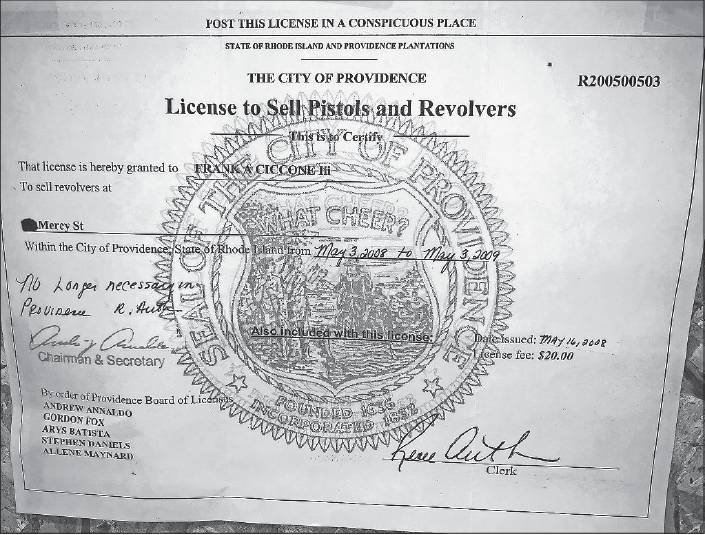

More than 10 years ago, a longtime Providence gun dealer went to the city to renew his license to sell pistols and revolvers at retail.

The city Board of Licenses told him he didn’t need to bother anymore, he said. To memorialize the arrangement, a city official hand-wrote on the license he’d gotten year after year: “No longer necessary in Providence.”

That’s a surprise to the attorney general’s office, which says local gun-dealer licenses are still necessary — it’s a state law. Cities and towns can’t simply waive a requirement to license gun dealers, the state’s top lawyer said.

The dealer in question may also come as a surprise, because he has another, more high-profile job: he is state Sen. Frank A. Ciccone III, Democrat of Providence.

The third and final surprise is where Ciccone sells the guns: from the basement of his Mercy Street home, in the residential Silver Lake neighborhood.

“Basically, I do it for people that I know,” Ciccone said in a phone interview.

Dealing guns from home is legal around the country, so long as the dealers have the proper federal license. Wherever they’re based, they must still follow standard gun-transaction laws, like conducting background checks on buyers.

Ciccone, like 83 other people and companies in Rhode Island as of September, has a federal license through the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives allowing the sale of guns at retail and wholesale. (The license also allows people to do gun repairs and act as gun consultants, but Ciccone is a dealer.)

Like a smaller portion of people in the state, though, he does not have a currently valid retail gun dealer license from his city — because, he said, Providence told him he no longer needed one.

“There’s probably some disconnect somewhere along the line in Providence,” Ciccone said. “I haven’t the slightest idea why they did it.”

Neither, it seems, does the city, which said it does not even have any records about a policy change. The city at first said it wasn’t required to issue the licenses to these retailers, then, finally, disputed that the city even had any.

It does.

Ciccone’s low-volume side business underscores a fact about the retail firearms industry in Rhode Island and around the country: It’s not just for pawn shops and outdoor supply stores, but neighborhoods around the state, too.

“People who operate from their residence are still held to the same standards as retail locations,” said Nicholas O’Leary, director of industry operations for the ATF in New England. “We still assess on an ongoing basis who we go to see, and it doesn’t necessarily matter if they have a retail location versus a home. At the end of the day, ATF’s mission is to protect the public from gun crime.”

It also highlights the way local enforcement of retail firearms dealer regulation can vary in Rhode Island, despite a state law calling for across-the-board licensing of retail gun dealers. The local licensing oversight of gun dealers ranges from public votes before a city or town council (Exeter and Woonsocket) to nonexistent (Providence and Richmond).

“Local licensing could, if implemented effectively, bring additional accountability to the sale of products designed to take life,” said Ari Freilich, staff attorney for the San Francisco-based gun-control organization Giffords Law Center.

There is some dispute about what the law on licensing gun dealers actually means. So The Providence Journal asked the state’s top lawyer, Attorney General Peter Neronha, for his take. His office said the dealers do need to get local licenses. (Those are in addition to the licenses required on the federal level.)

“State law provides that cities and towns have the discretion whether or not to issue licenses to gun dealers,” Kristy dosReis, a spokeswoman for Neronha, said in an email. “However, the law also provides that gun dealers cannot operate without a license issued by the city or town in which they operate. While this provision of Rhode Island law has never been interpreted by a Rhode Island court, we do not believe that cities and towns have the authority to waive the license requirement that is imposed by state law.”

Some towns, though, argue that they don’t have to issue retail gun-dealer licenses, because the dealers are already regulated through ATF.

That’s the explanation Providence originally provided when asked why it didn’t issue licenses to retail gun dealers in the city.

“[W]hile state law allows the city to issue these types of licenses it does not require the city to do so,” Emily Crowell, a spokeswoman for Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza, said in an email in December. “Since these retailers are federally regulated through ATF, they would have the most updated information.”

So the city is choosing not to license retail gun dealers in the city? No, the city later clarified. Although the city had just a few weeks earlier deferred to federal authorities about “these retailers,” now it said it didn’t have any such “retailers.”

But the city acknowledged that there are entities in the city that “transact” guns under a federal license. So why aren’t they “retailers”? Here’s the city’s definition of a retailer: Someone with a retail sales permit from the Division of Taxation.

Ciccone said he has a retail sales permit from the Division of Taxation. He even provided a photograph of it.

The city did not respond to a follow-up question about why Ciccone isn’t a retailer by its own definition.

To be a retailer, there’s no requirement under state law that someone have an “Open” sign in the window or to be located in a traditional brick-and-mortar setting. They can indeed be based from a home.

Four other entities in the city have federal firearms licenses, or FFLs, allowing them to sell guns at retail. They all lack corresponding retail dealer licenses from the city of Providence. None was available for comment. Two appear to be defunct, or at least not in the same location that’s listed in federal records. One holder of a federal license to deal guns is Henry Oil Co., better known for dealing oil, diesel and gasoline. (The owner declined to comment.)

“At this time, our licensing and public safety teams are reviewing the current FFL’s and will consult with the law department and the [attorney general’s] office if there is any change,” Crowell said in an email.

And what about that pen-made policy change on the face of Ciccone’s license?

Crowell also said the city could not confirm the authenticity of the license with the hand-drawn exception that Ciccone provided, but the city also did not challenge it. The city hasn’t received an application or a request for an application in at least 10 years, Crowell said. (The city also doesn’t have an application for one on its licensing website, Ciccone noted; he checks every now and then and would be willing to submit one.)

Andrew Annaldo, chairman of the Board of Licenses at the time Ciccone said he got his last license, said he didn’t recall ever issuing them — much less a decision to stop doing so.

Told his name was stamped on the license Ciccone provided, Annaldo said: “Thousands and thousands of licenses have my name on it.”

Told, in turn, that the city said it couldn’t verify his license was legitimate, Ciccone scoffed. He keeps the old license with the hand-drawn addendum hanging for posterity in his business, and considers himself grandfathered in as a retail firearms dealer in his city.

“It’s got a number on it,” Ciccone said. “They have the books, I don’t. That’s ludicrous.”

One easy way to tell that the state’s retail gun-dealer licensing law hasn’t changed much in decades, or been considered for an update recently, is how much towns are supposed to charge for a license. It’s just $5. (Some towns charge more.)

Dating to 1959, the law is relatively obscure, and light on details: It says that to sell or transfer firearms in Rhode Island, retail dealers must be licensed as set out in state law. Anyone who’s selling or transferring guns, or who has guns and is planning to sell or transfer them, must get a dealer license once per year from their city or town in a form drawn up by the attorney general. They must only do business in the building listed on the license and follow other relevant laws. They must also keep the license posted.

That’s about the extent of it. Compare that with New Jersey’s requirements: an entire unit of the New Jersey State Police is dedicated to retail firearms oversight. Not only do gun dealers have to get licensed in New Jersey — their employees do too. Applicants for a state license in New Jersey also have to get written zoning permission before they set up shop.

None of that is required in Rhode Island, but most communities here are still following this state’s less-restrictive local licensing law.

Exeter, for example — which doesn’t even have a police department or town manager — requires its dealers to disclose their ownership. In Woonsocket, like other places, the gun dealers come up for a vote in the City Council. Tiverton asks firearms dealer applicants whether they’ve been arrested, where they’ve lived for the past three years, and their height, weight and hair color.

A month ago, The Providence Journal asked every city and town in the state for records showing applications for gun dealer licenses. Most responded with the records of the local licenses they’ve issued. Others said they did not have any such records of licensing gun dealers on the local level — even though the ATF listed gun businesses in those towns.

It’s difficult to make a one-to-one comparison between having a federal dealer license and needing a local dealer license. The federal license also allows people to do gunsmithing, and some people with dealer licenses said that’s all they did. Others are no longer in business.

Representatives for some towns where people held federal dealer licenses, but no local dealer licenses, said the businesses were inactive or hadn’t dealt guns in years. They included East Greenwich, West Greenwich, Hopkinton, Warren (where there’s a gun range that doesn’t sell guns at retail) and Bristol (where there’s a gun repair business that doesn’t sell guns).

Lincoln also had discrepancies between the number of locally and federally licensed dealers. As of September 2019, the town had two people with federal licenses to deal guns, but had not licensed them on the local level. T. Joseph Almond, the town administrator, acknowledged that the town’s police chief had processed firearms purchase applications for at least one of the dealers.

“We are awaiting legal advice on ensuring compliance with the local license requirements pursuant to state statutes,” Almond said in an email.

Like Providence, the town of Richmond said it has no record of issuing the licenses.

Unlike Providence, the town was straightforward about why it doesn’t: It doesn’t have to, its lawyer said.

Karen Ellsworth, the solicitor for the town of Richmond, pointed out that the state license requirement was enacted in 1959, before the federal Gun Control Act of 1968 went into effect.

“I think passage of the federal law has made the local dealer licensing procedure largely irrelevant,” Ellsworth said in an emailed statement.

Richmond has two federally licensed gun dealers without local gun dealer licenses, including Hope Valley Bait & Tackle, the shop where a gunman bought a revolver and opened fire at his housing complex in Westerly on Dec. 19, killing one. The shop’s owner and manager said they were unaware of any local license requirement in Rhode Island, but said they strenuously follow the law and have never had a problem in 40 years.

Here’s what the law on getting a local dealer license — 11-47-38 — says: “No retail dealer shall sell or otherwise transfer, or expose for sale or transfer, or have in his or her possession with intent to sell or otherwise transfer, any pistol, revolver, or other firearm without being licensed as provided in this chapter.”

The next section, 11-47-39, says: “The duly constituted licensing authorities of any city, town, or political subdivision of this state may grant licenses in form prescribed by the attorney general effective for not more than one year from date of issue permitting the licensee to sell pistols and revolvers at retail within this state,” with some conditions.

One quirk in the law jumps out: 11-47-38 speaks to licensing all firearm dealers, but 11-47-39, which lays out how the licensing should take place, only deals with pistols and revolvers.

But as often happens in debates over gun laws, the real key word there is “may.” The issue comes up in the context of permits to carry guns. Some states are “may” issue states — authorities may give out carry licenses, or may deny them in particular cases if they choose, bestowing them with broad discretion to deny or approve them. Other states “shall” issue those licenses, giving them less leeway to deny them.

The distinction has also played out within Rhode Island, which has a little of both. Licensing authorities in a city or town “shall” issue licenses to carry pistols or revolvers to an applicant if it appears “that he or she is a suitable person to be so licensed.” Meanwhile, the law says the attorney general “may” issue those licenses to carry pistols or revolvers.

In the case of gun dealers, the dispute over the word “may” boils down to this: What does it mean that licensing authorities “may” grant the licenses? The state attorney general says it means a town may grant a license to a particular gun dealer, or deny it, but if the business doesn’t get it, it can’t legally operate.

Some towns, though, have read the word to mean they “may” decide to issue licenses to the gun dealers in their town, or they may decide not to bother with it, relying instead on the federal licensing requirements under the ATF to oversee the gun dealers in town. That’s what’s happening in Richmond; Hopkinton, likewise, interprets the word that way, although the town’s lawyer said none of its federally licensed dealers are currently selling at retail, making it a moot point.

Gun-rights lobbyist and activist Frank Saccoccio, of the Rhode Island 2nd Amendment Coalition, sides with Providence, Richmond and Hopkinton.

The gun dealers still have federal licenses, after all. The businesses already go through the ATF process, subjecting themselves to random inspections which could come 24/7. The licenses are not for hobbyists or collectors. It’s legal to sell a gun without a dealer license, but to get into the business, dealers need one. They’re for people trying to make money by selling guns. Nobody’s setting up shop in their basement on a lark, Saccoccio said.

If they do need local licenses, though, and they don’t have them because their town told them they didn’t need them, that’s on the town, not the gun business, Saccoccio said.

“I think every gun dealer would apply and get the license” if it was required, he said. “They don’t want to get in trouble over five dollars. Every single one of them would do it.”

Ciccone, the Providence state senator and gun dealer, is one of them. He’d be happy to pay the money ($20 when he last paid it) to make sure he was following the law.

He’s exacting, even though his business isn’t exactly high-volume: His sales amount to the single digits a year; in 2019, he sold one gun and “transferred” one. In other years he’ll do two or three transactions, he said.

Gun transfers often take place when someone buys a gun from out-of-state — often through a website like Gunbroker.com. Gun buyers can’t have it shipped directly to themselves. Instead they must send it to a federally licensed gun dealer, like Ciccone, who will accept shipment and help with the paperwork. In one instance, for example, a client won a gun in a raffle out of state. It couldn’t be shipped to the client, who didn’t have a dealer license, so the gun was sent to Ciccone, who was able to process the paperwork and get his client the gun under his federal firearms licenses.

Ciccone’s love of hunting inspired him to get the federal gun-dealer license, he said. He said the federal license dates to the late 1980s or early 1990s, and that while the focus of the business is hunting, he also sells handguns.

Although he doesn’t have a storefront, Ciccone can perform all the legal tasks that someone with a brick-and-mortar business can, including a background check.

Gun enthusiasts like him tend to be careful about safety and security, he said. In the world of guns, he said, the types of people who let ATF into their businesses, and their homes, are not the problem.

“It’s a responsibility,” Ciccone said. “It’s a responsibility of buying it, of knowing how it operates, and the safety of it, and the storage of it.”

The Providence Journal

Watchdog Team can be reached at watchdog@ providencejournal.com or (401) 277-7777.

Have a tip?

To report a tip to The Journal’s Watchdog Team, call (401) 277-7777 or email watchdog@providencejournal.com