BROWN UNIVERSITY

Dinners offer peek at culture of privilege

Invitation-only networking events benefit children of the rich and famous

By Lucas Smolcic Larson, Julia Rock, Harry August and Jesse Barber Special to The Journal

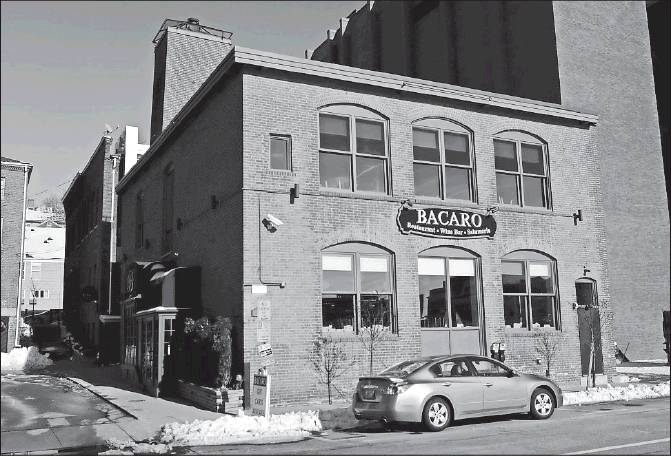

PROVIDENCE — On a mild Wednesday evening in October, patrons approached the doors of Bacaro on South Water Street, only to encounter a posted notice that the upscale Italian restaurant was “closed for a private event.”

By 7 p.m., Ubers, punctuated by the occasional privately owned Audi and Land Rover, began dropping off groups of Brown University students wearing blazers, dresses and high heels. The students were there by special invitation for the “Marty Granoff Dinner.”

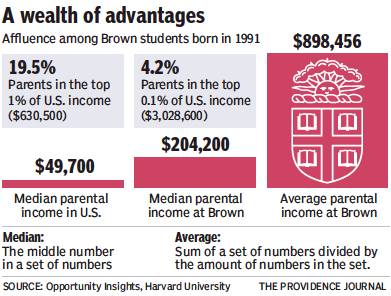

Even at a university that tops the Ivy League in admitting wealthy students (the median parental income of a Brown student is $204,200, and 19 percent of the student body comes from the top 1 percent of the income scale, according to data collected by a research team at Harvard University and published in The New York Times), the profile of Granoff’s guests stood out.

Dinner attendees included the children of an elite group: preeminent U.S. politicians, CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, business executives, financial moguls and otherwise wealthy individuals. To re-create the guest list, said one student attendee, “Just look up the names of buildings [on campus] and look up people with matching last names — that’s it.” Another attendee added that as the daughter of two doctors, she thought almost all of the dinner guests “are richer than I am.”

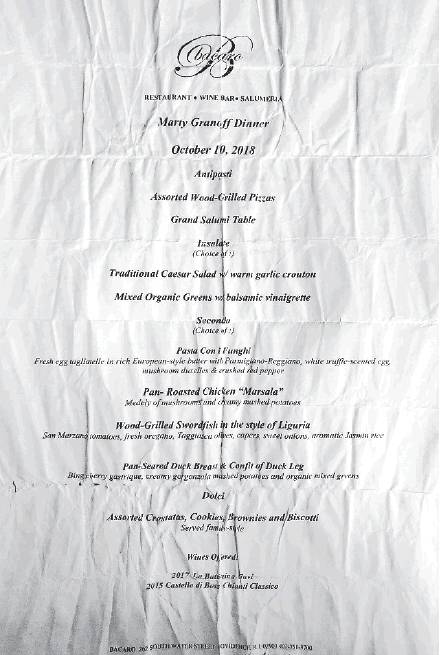

Inside Bacaro, wine flowed freely. After an hour of mingling over drinks, wood-grilled pizzas and a “Grand Salumi Table,” the guests — some 60 students, alumni, faculty and staff — retired to the second floor for a three-course meal, choosing from pasta with truffle-scented egg and mushroom duxelles, pan-roasted chicken Marsala, wood-grilled swordfish, and pan-seared duck breast. A coordinated team of wait staff expertly filled glasses, took orders and whisked plates from tables. (Bacaro’s owners did not respond to requests for comment on this story.)

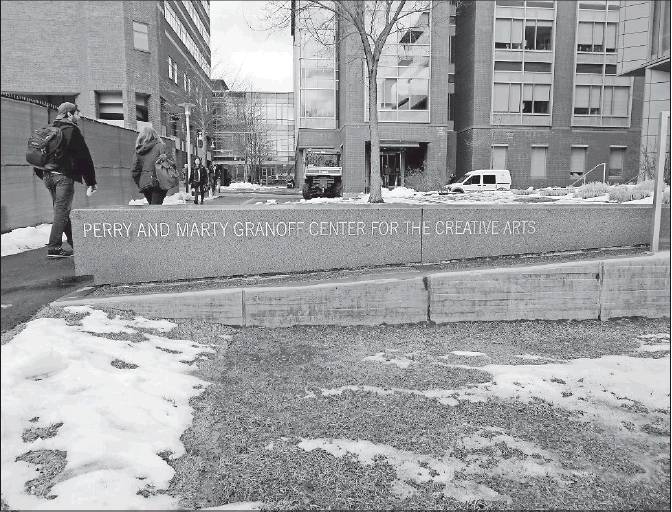

At the center of it all, one man presided: Martin J. Granoff, 82, a former textile industry executive, Brown trustee emeritus, sponsor of student scholarships, and the lead donor behind Brown’s Perry and Marty Granoff Center for the Creative Arts, located on Angell Street. Granoff not only picks up the minimum $9,000 dollar tab for the Bacaro dinners (estimated from a cost sheet provided by the restaurant), but curates the selection of students in attendance, favoring students from Brown’s most elite families.

Each semester, Granoff creates the invitation-only networking event primarily for some of Brown’s wealthiest and most well-connected students, all with the blessing and support of the university’s Advancement office. A university spokesperson said that the dinners are not considered “official university events,” but acknowledged that the Advancement office “provides some logistical support.”

Some past attendees have collected business cards from alumni and spoken with them about jobs, while others, student guests say, have used their connection to Granoff or other trustees to bypass university processes and gain better housing from the Brown Office of Residential Life.

Wealth and power give prospective students a leg up in the university admissions process at Brown and other elite schools, largely through the practice of favoring children of alumni — so-called legacy students — and actively pursuing the children of potential donors and celebrities, a practice documented in books by journalist Daniel Golden and sociologist Jerome Karabel, among others.

But the Granoff dinners show that these privileges do not end with an acceptance letter.

“It is bad enough that Brown provides legacy preferences in admissions — essentially affirmative action for the rich,” wrote Richard Kahlenberg, senior fellow at the Century Foundation and an expert on socioeconomic inequities in education, in an email. “Separate dinners for wealthy students send a terrible message about Brown’s commitment to inclusion.”

Brown President Christina Paxson has referenced a “commitment to bringing the best and brightest students to Brown regardless of their socioeconomic background” in university statements. And the university administration has made strides in recent decades toward opening its gates to students of all backgrounds, in 2003 becoming the last Ivy League school to introduce need-blind admission for domestic applicants and replacing loans with grants in financial aid packages this school year.

But the Granoff dinners undermine that commitment, said Shawn Young, a Brown student-activist dedicated to increasing access to the university and expanding support for first-generation and low-income students.

“[If] there are actual real differences in the way that students are treated as a function of how connected they are to influential members of the Brown community,” he said, “that’s straight-up wrong.”

To understand the Granoff dinners — events that few students are aware of — two student journalists at Brown attended one dinner, uninvited, on Oct. 10, 2018. At the door, we were asked if we had responded to an email invitation. We said we had not responded (we did not receive the email), gave our names, received name ,tags and were allowed inside. We ate dinner and observed as outsiders.

We also interviewed 12 current and former Brown University students who have attended one or more Granoff dinners, almost all of whom requested anonymity as a condition of speaking to us, due, they say, to concerns about Granoff’s connections to their parents, his influence at Brown, and how they might be perceived for attending the dinners. One student attendee explained, “It’s almost kind of exclusive. … I get the idea behind it, but also I try not to bring it up because other people are like, ‘Oh, this is special treatment.’”

More than a dozen other Granoff dinner guests did not respond to interview requests, or declined to comment.

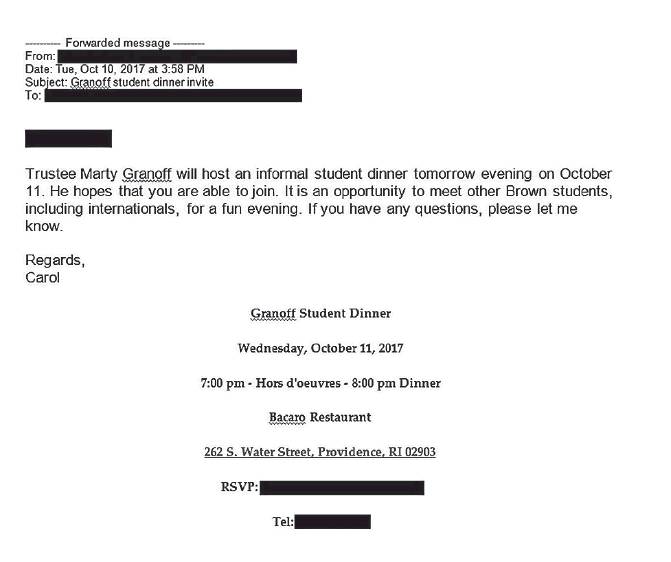

The students interviewed for this story were all invited to the dinner via email from one of three employees in the university’s advancement office: Vice President for International Advancement and Senior Advisor for Leadership Philanthropy Ron Margolin, Assistant Vice President for International Advancement Joshua Taub, or International Advancement Program Coordinator Carol Beliveau.

The email invitations to the dinner are brief: “Trustee Marty Granoff will host an informal student dinner on October 10. He hopes that you are able to join. It is an opportunity to meet other Brown students, including internationals, for a fun evening. If you have any questions, please let me know.”

“Multiple times a year, Mr. Granoff hosts dinners for students he has come to know or become aware of through his many years interacting with Brown families,” Brown University spokesman Brian Clark wrote in an email.

Clark said that the dinners “are not considered official University events” and are paid for by Granoff, but staff in the Advancement office provide “logistical support” for the dinners, including “sending invitations, managing responses, and event planning tasks along those lines.” Attendees of the dinner received printed name tags stamped with the Brown University seal.

When asked about the purpose of the events, Clark said: “We understand that the goal of his dinners has been to foster a strong sense of community among the students who attend.” Clark said, “One thing that distinguishes [Granoff’s] generosity is his love for students.”

Granoff, who goes by “Marty,” is the founder and former chairman of Val D’or Apparel, a knitwear manufacturer, and he has held top positions at other national textiles companies. Granoff’s daughter Gillian graduated from Brown in 1993, and as a university trustee, he served on multiple committees of the Brown Corporation, receiving an honorary degree in 2006. He is a significant donor to the arts, Jewish student organizations, and scholarships at Brown, Tufts University (where a performing arts center also bears his name), and elsewhere.

In 2001, Granoff and his wife, Perry, gave $1.4 million to Brown to establish a scholarship fund for descendants of first responders killed in the Sept. 11 attacks, in the name of Charles Margiotta, a firefighter and Brown alumnus who died at the World Trade Center. Between fiscal years 2011 and 2014, the Perry and Marty Granoff Family Foundation, of which Granoff is president, disbursed $4.4 million to various causes, according to tax filings, and in February 2013, Brown University received a $10-million donation from him.

In 2011, during a dedication ceremony for the newly constructed Perry and Marty Granoff Center for the Creative Arts at Brown, Granoff told the audience, “I love to convince people that wealth distribution is significantly more attractive than wealth accumulation.” (Granoff led fundraising for the $40-million building.)

Granoff has also sponsored a class at Brown titled “Investing in Social Change: The Practice of Philanthropy,” in which groups of students are given thousands of dollars in lump sums to donate to local nonprofit organizations.

Granoff did not respond to repeated requests for comment on this story, including emails, letters to his personal residences, calls to his family foundation and son Michael Granoff, messages forwarded by former employers, and text messages from a dinner attendee who forwarded requests to his personal phone number.

When asked about the students who attend the dinners, Clark said, “These students include many international students, recipients of Mr. Granoff’s scholarships, students who are friendly with the students he knows, and many students who represent different aspects of student life.”

Clark declined to provide a guest list for the October 2018 dinner, so there was no way to verify the background of each guest.

But dinner attendees are aware of the profile of the majority of their fellow guests. One student explained, “You either personally know Granoff or you’re there because your parents’ names are in the news for some reason or another.” Another added that there’s talk of who’s who: “There is definitely gossip about them, ‘They are the son or daughter of [whomever].’”

One dinner attendee, first-year Naomi Shammash, said that she did not think Granoff deliberately invited the wealthiest students at Brown: “I don’t think he chooses to invite wealthy kids. I just think they are the kids of his friends, and connections arise from that.” Shammash added: “Everything [Granoff] does comes from a place of generosity — he wants everybody to be happy.”

At a previous dinner, an attendee said that Granoff told the invitees: “‘The reason why I set up these dinners is because I want you guys all to get to know each other. You know, you might get married to each other. … Someone in the past met their future wife here — so mingle more, you guys!’ stuff like that.”

Another guest reported that during the cocktail hour before this October’s dinner, Granoff said: “I do these dinners so people who would not usually get to know each other do.” As a result, one attendee likened the dinners, which happen twice a year, to a “club” of sorts.

“It is these hand-picked students,” another attendee said. “It’s so hard to infiltrate by anyone else.”

Several students claim the dinners serve an additional function: securing favors through connections to Granoff, including preferential treatment from Brown’s Office of Residential Life.

Residential Life limits the number of students permitted to live off-campus, outside the university dorm system. One student said that a close friend and roommate, who has attended multiple Granoff dinners, contacted Granoff after being denied permission to live off-campus (only seniors are guaranteed permission, and the Granoff dinner attendee was an underclassman at the time). The source said that Granoff set up a meeting for the attendee with Associate Director of Residential Life Richard Hilton. Soon afterward, the source said, the attendee received off-campus permission.

Another student said that a friend and fellow dinner attendee gained better on-campus housing through his connection with Granoff. Both students who reportedly gained preference in housing procedures declined to comment.

When asked specifically whether Granoff or other donors have intervened in the university’s housing processes, Hilton wrote in an email that “Each year, we hear not only from students, but from parents, family members, friends, faculty, staff, alumni, donors and others who contact us to advocate on behalf of specific students. We understand and appreciate all of that outreach.”

Hilton repeatedly declined an interview to discuss how this advocacy by donors and others affects the housing process, describing the system as “equitable.”

“No individual needs to intercede on a student’s behalf for us to accommodate a preference,” he wrote.

A former employee in Brown’s Office of Residential Life, who requested anonymity for fear of professional repercussions, explained that students who are children of trustees or otherwise connected to influential people “were able to get certain things done” regarding housing requests, but could not confirm specific allegations related to Granoff.

For example, this employee was instructed by a supervisor to meet with a student who had been trying to get a room change. The employee explained, “I just didn't think his reason was valid enough,” but “his mother was on the board of trustees, and then I was forced to have a meeting with him.” The student got the room change. When asked about the Granoff allegations, the employee said, “It’s not shocking.”

The existence of the exclusive dinners and allegations of special treatment for the students who attend them did surprise Shawn Young, the student-activist.

The “little backroom dealings that affect internal administration processes” described by Granoff dinner attendees, are “just offensive to the work that a lot of people are trying to do to make Brown’s campus more accessible to first-generation and low-income students,” said Young, who, in collaboration with the educational nonprofit EdMobilizer, coordinated the spring 2018 #FullDisclosure campaign to force the university to make public its policy on legacy admissions.

Preference for applicants related to alumni has been criticized for perpetuating class divisions at elite schools. At Brown, Young collected the necessary signatures for a ballot question put before the student body over whether the university should disclose legacy admissions policies and data. It passed, and he reports that a closed-door committee of students and administrators is currently preparing a report on increasing access to the university for first-generation and low-income students.

Gains for these students, like those won as a result of #FullDisclosure’s call for transparency, are hard-fought — the result of years of organizing “just to get a place at the table,” said Young.

In 2016, after student-activists developed and proposed the idea, Brown established a First-Generation and Low-Income Student Center: a space for these students’ advocacy and community (the center has since modified its name to encompass support for undocumented students). Then, beginning with the 2018-2019 school year, the university replaced all loans in financial aid packages with grants (which do not have to be repaid) and began to automatically waive the $75 application fee for low-income applicants (previously, these students had to request a fee waiver).

But if the allegations of favors for wealthy students stemming from the Granoff dinners are true, “a small group of students are being treated differently by the administration, and that's sort of hamstringing the work that the school has already done to help students who don't come into the school with those influences or with that social capital from being connected to the Granoffs,” said Young.

Richard Kahlenberg, the Century Foundation fellow, adds: “Hosting a special school-sponsored dinner for the wealthiest and most well-connected students, and excluding everyone else, underlines how culturally acceptable the worst kind of class discrimination remains at elite colleges today.” Kahlenberg said, “I don't personally know of similar events at other institutions.”

The Granoff dinners fit with the picture of the Ivy League painted by journalist Daniel Golden in his 2006 book, “The Price of Admission: How America’s Ruling Class Buys Its Way into Elite Colleges — And Who Gets Left Outside the Gates.” Golden describes “the preferences of privilege,” benefiting “the wealthy and powerful across the political and cultural spectrum” in admissions at selective private universities, where money and prestige tip the scales in favor of these applicants.

In a chapter on Brown, Golden writes, “No university in the country has practiced celebrity admissions more assiduously or successfully,” alleging that the university consciously sought out high-profile students to “turn a place such as Brown into a ‘hot’ school despite a lagging endowment and blue-collar surroundings.”

According to Golden, Brown even employed a “behind-the-scenes liaison to the rich and famous whose children were seeking admission”: a man named David Zucconi, whose eventual downfall came in 1999, when he was caught offering Brown University Sports Foundation money to Brown sports recruits in violation of Ivy League rules.

Compared with a secret admissions liaison, the Granoff dinners seem unremarkable — a low-profile example of the unique opportunities offered to wealthy students at elite schools. However, Kahlenberg faults the dinners for the message they send about which students are valued at the university: “Colleges like Brown should be doing everything they can to make low-income students, who are greatly outnumbered, more comfortable, not less,” he said, “A dinner like this just reminds less advantaged students how marginalized they are.”