MY TURN CATHERINE W. ZIPF

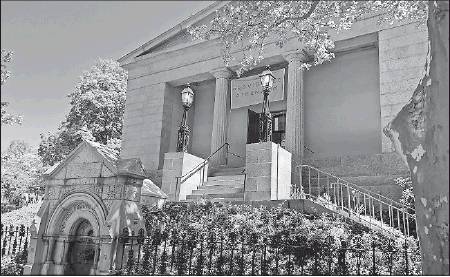

The wonderfully Greek Providence Athenaeum

The Philadelphia-based architect William Strickland has a curious connection to Rhode Island.

Strickland worked in the early part of the 19th century. He trained in Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s office and earned his first major commission, the Masonic Hall in Philadelphia, in 1808.

In 1818, Strickland won the commission for his most famous building, the Second National Bank of the United States, also in Philadelphia. The Second National Bank’s facade contained eight fluted Doric columns supporting an entablature and pediment, all copied from the Parthenon.

The imitation is key here. Many scholars consider Strickland’s bank to be the first Greek Revival building in America. It is characterized as Greek Revival (as opposed to generally neoclassical) because it borrowed literally from a Greek source. Strickland made it OK to quote directly from other buildings. The more authentic the quoting, the “better” the architect.

On the one hand, copying the Parthenon was easy. James Stuart and Nicholas Revett’s 1762 book, “The Antiquities of Athens,” included measured drawings of the Parthenon. Strickland, who had never been to Greece, used these measurements for his bank design.

But copying had its challenges. The symbolism of Greek architecture transferred well to the American context — both reflected buildings of a democratic society. But, Greek buildings did not always suit the American climate. For the Second National Bank, Strickland opted not to copy the Parthenon’s side colonnades because it did not result in useful space.

Furthermore, the Greeks didn’t have banks, per se. They did have treasuries, but these functioned differently. Strickland had to create what a Greek bank looked like. Picking the Parthenon, the single most important religious building in Greek culture, as a model for an economic building was a pretty gutsy move. It reads as capitalism replacing religion.

Fascinating history, but what does Rhode Island have to do with this?

Strickland worked mostly in Philadelphia and Nashville. He built only one building in all of New England. That building is located in — drum roll — Providence! It’s the Providence Athenaeum, at 251 Benefit St.

The Athenaeum (it became the Providence Athenaeum later on) formed in 1836. It partnered with the Franklin Society to raise money to construct a new building. Strickland, though an outsider to Rhode Island, got the commission because he was a member of the Philadelphia’s Franklin Society chapter.

For the Athenaeum, Strickland designed a small but monumental temple set on a high basement almost a full story above street level. From this perspective, the building appears to be larger than it is and must be viewed from below. This scheme is very Greek. Greek temples are often raised up and approached from below.

Another Greek characteristic was to force viewers to approach from the side. The Athenaeum is accessed from one of two side staircases that meet at a central staircase in the front. This indirect path forces different views of the building, creating an appreciation for its size, scale and mass.

And, of course, the architecture was Greek. On the facade, two Doric columns are set between two wings, an arrangement called “in antis.” While not a literal copy of an original Greek building, the design recalls temples dedicated to the Athena, the goddess of wisdom. The reference is fitting for a library and (ahem) Athenaeum.

The building has its own Rhode Island flair. For example, the granite is from Johnston. Nonetheless, when it opened on July 11, 1838, the Athenaeum, with the Franklin Society occupying its lower level, was widely recognized as a Greek design. And with that, Providence added a “Strickland” to its urban landscape.

I am always delighted when Rhode Island’s architecture intersects with outside trends. We have an amazing collection of historic buildings. Knowing more about them enriches us all. If you haven’t seen this building, please make a point of walking by.

— Catherine W. Zipf, a monthly contributor, is the executive director of the Bristol Historical and Preservation Society.