LIVING WITH DEMENTIA

When Alzheimer’s joins holiday table

By Stacey Burling STAFF WRITERUnder the best of circumstances, it’s hard to live up to holiday expectations of unswerving, picture-perfect traditions and family bliss. Sisters feud about hosting. Uncle Pete has too much wine. Nephew Max wants to talk about the election.

There can be tension long before you add one of the saddest stressors to multi-generational festivities: dementia. But, if there was ever a prod to get real about what you expect from Thanksgiving — and what the holiday is really about — this is it.

We spoke with some experts — Denise Brown, founder of Caregiving.com ; Ruth Drew, director of information and support services for the Alzheimer’s Association; Felicia Greenfield, a social worker who is executive director of the Penn Memory Center, and Jill and Elizabeth Egan, New Jersey sisters in their 20s whose father and grandmother have Alzheimer’s disease — about how to arrange holiday celebrations so that everybody, including people with dementia and their caregivers, can have a good time.

“It really comes down to the time spent together and the connection between people who care about each other,” said Drew. Families may need to reevaluate their traditions every year. “It doesn’t have to be at a specific place. It doesn’t have to be a specific menu. It doesn’t even have to be a specific day.”

Worries about an older relative’s health may increase the desire for a perfect holiday. “The concern is that this might be the last holiday and that’s where the pressure comes from,” Brown said. “It’s important to be realistic and it’s important to know that the most memorable holidays are the ones where you’re able to share quality moments with each other.”

Keep in mind that it’s the healthy people in the room who need to make adjustments. The person with Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia has a damaged brain. “They are doing the best they can with the brain they have,” Drew said. “We’re the ones with the healthy brain. We’re the ones who can be flexible and be accommodating.”

Start with realistic hosting ideas. A traditional host who is also a caregiver may not have the energy to take on all the usual Thanksgiving meal work. This may be a good time for others to bring more food or buy cooked food from the grocery store or a restaurant. Drew said one family also asked relatives to sign up for one-hour shifts spent hanging out with the person with dementia.

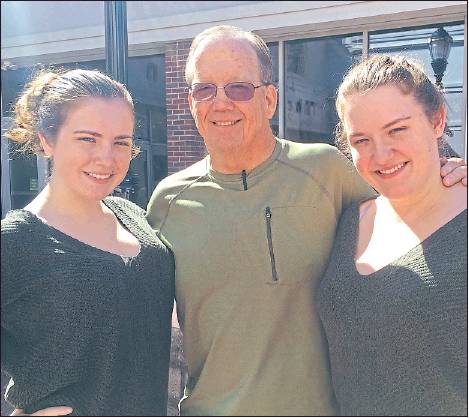

Educate other guests. Tell them what to expect from the person with dementia well before the dinner. This should be an update on how functioning has changed, what stresses the person out and what kind of conversation is possible. The Egan sisters call other family members to tell them how their father, Tom, who has early-onset dementia that is progressing rapidly, has changed. For example, he may not recognize people and can be difficult to understand when he talks, but enjoys conversations about things he did in his youth. On its website, the Alzheimer’s Association has a model letter that caregivers can distribute.

Keep it simple. People with dementia are easily confused and over-stimulated. If possible, keep the noise down and have a quiet room available for rest. Remember that people with dementia do best with a routine and familiar surroundings. If those have been disrupted, be understanding. Unfortunately, music and candlelight can make things worse. Bright lights are best for preventing confusion. People with dementia may not be able to handle an all-day celebration.

One-on-one conversation is best. While people in the early stages of dementia may love to have large families around them, those with m o r e ad - vanced disease often do b e t t e r i n small groups, Greenfield said. Even then, it can be hard for people with de-m e n t i a t o keep up with fast-paced conversations across the table. “Look them in the eye and speak loudly and clearly and slowly,” she said.

It’s not uncommon for people with dementia to tell stories repeatedly or to tell stories that aren’t true. There’s no point in trying to correct them. “Who cares? Just go with it and try to have fun with it,” Greenfield said. The “feeling of connection,” Drew added, is much more important than the facts of the story.

If possible, keep people with dementia involved. Last year, Tom Egan, now 66, peeled potatoes and peeled apples for a pie he later proudly claimed to have made himself. He put the tablecloth on the table. Others may enjoy chopping vegetables, doing simple crafts with the kids, folding napkins or watching football. Many love looking at old family photos and talking about them. If you want people with dementia to help, tell them what to do one step at a time. Many can’t remember multi-step tasks.

Don’t be surprised if there’s a meltdown. Drew tells families that “unexpected behavior is one form of communication.” Try to figure out whether the person with dementia is in pain, tired or overwhelmed. Think in advance about things that might be soothing.

Don’t stress about the food. Many people with dementia lose their appetites. They may not eat much turkey, but they often love dessert. Let it be. Alcohol is another story. It makes brain functioning worse in normal people. People with dementia shouldn’t have much of it, Greenfield said. She recommends the “loving deception” of non-alcoholic wine and beer for dementia patients who like to drink.

Dementia and travel may not go well together. Dementia often gets worse in unfamiliar settings and when routines have been disrupted. If you must travel, allow extra time to minimize stress. “Being patient is key to everything because my anxiety and stress will feed onto him, ” said Jill Egan, 21, of Gibbsboro, who helps get her father ready to go to an uncle’s house for Thanksgiving. During the workweek, she is the primary daytime caregiver while her mother works as a college professor. Elizabeth Egan, 26, said her family has to be prepared for the possibility that her father will refuse at the last minute to go to her uncle’s house for Thanksgiving. It’s already happened once. “We’re not going to force it because the situation just really goes downhill if you try,” she said. “We ended up going to a diner. It wasn’t bad. It was our family.”

If people with dementia live in an assisted-living facility or nursing home, families often wonder whether to take them out for holiday celebrations, experts said. Most decide to celebrate in the facility and possibly have another family celebration somewhere else. The Egans go to their grandmother’s nursing facility to celebrate with her because, at 90, she is no longer comfortable traveling.

Practice gratitude. The Egans have happy memories of large Thanksgiving and Christmas gatherings, but appreciate what they have now.

“I am grateful and happy that I’m able to have any Thanksgiving with my family, even if it’s at the diner,” Elizabeth said.

Greenfield said that one of the techniques for coping with dementia that she teaches families is practicing gratitude. “We try not to focus on the losses,” she said.

Calls to the memory center always go up this time of year after people reconnect with someone they haven’t seen for a while and notice worrisome changes. The classic case is an experienced and previously successful hostess who suddenly can’t pull the party together. If you see changes in memory or the ability to plan, you can get feedback from a doctor, the Penn Memory Center or from the Alzheimer’s Association’s 24/7 Helpline, 800-272-3900. sburling@phillynews.com

215-854-4944

@StaceyABurling