INQUIRER EXCLUSIVE | ROTTING FROM WITHIN

FROM Dream Home TO Nightmare

Hundreds in the area who bought houses in last decade’s building boom now face a costly epidemic of water damage.

By CAITLIN McCABE and ERIN ARVEDLUND | STAFF WRITERS

The U.S. housing market was only just starting to soar in 2001 when Mitch and Cheryl Goldstein plunked down $25,000 for an empty Bucks County lot.

The couple, entering their early 40s, had long been saving for their dream home — a brand-new, ground-up Toll Brothers house. Known even then as “America’s Luxury Home Builder,” the locally based national company brimming with industry awards offered the kind of quality the Goldsteins coveted.

So the Goldsteins eagerly planned: They chose skylights, upgraded to coffered ceilings, and envisioned anursery for the little girl they hoped to adopt. Finally, they thought, in Toll’s new Buckingham Forest development, they would have the house they had worked so hard for. Even Robert Toll assured them of that.

“We take the responsibility of building your new luxury house very seriously,” the company’s cofounder wrote in a letter to new homeowners, including to the Goldsteins after they signed their agreement of sale. “Welcome to the Toll Brothers’ family.”

For years, it seemed, good fortune followed. The day they moved in, the adoption agency called with a match. Three years later, Toll was selling versions of their $446,000 home for nearly $150,000 more. They began referring to their home as their “little slice of heaven in Bucks County.” It was, Mitch said, all part of the dream.

That dream, however, turned out to be an illusion — and Toll, the Goldsteins came to realize, was no family. Rather, an invisible hazard had entered their house, damaging it from the moment the final stucco and stone had been laid.

The Goldsteins’ house was rotting.

And the damage was impossible to see.

Before Toll even handed them their keys in August 2002, the Goldsteins now know, water had been seeping into their new home. Every day with rain, drizzle, or high humidity from then on, water and condensation crept through the cracks and crevices of their house, turning its wooden insides into a giant sponge and decaying the boards that held the house together.

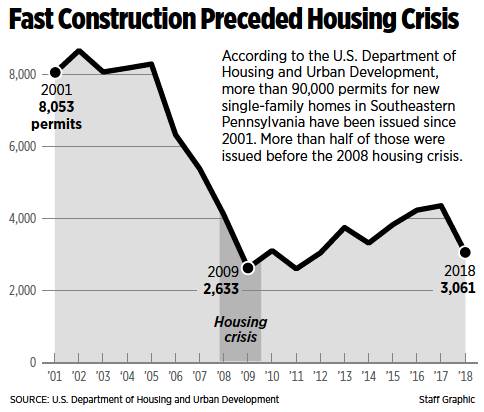

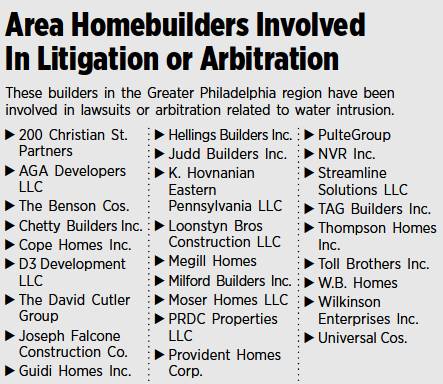

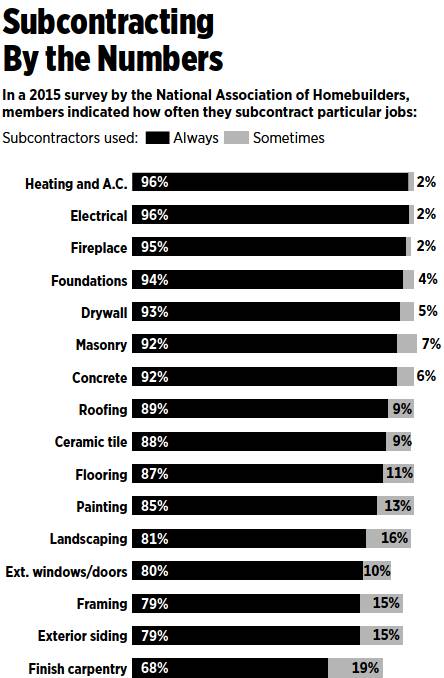

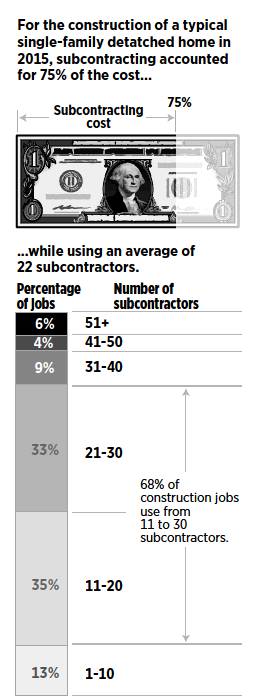

The Goldsteins are among hundreds of families in Southeastern Pennsylvania who bought new homes since the start of the 2000s housing boom, only to learn, years later, that shoddy construction overseen by at least 27 different builders has turned their asset — for nearly all, the most valuable they have — into a liability, an Inquirer investigation has found.

Among the Inquirer’s findings, based on interviews with more than 40 people, including nearly two dozen homeowners, several attorneys, inspectors, builders, and construction experts, as well as a review of thousands of pages of legal filings:

>Rushed production, under-trained workers, lower-quality materials, and lax oversight by builders and code inspectors have left more than 650 homeowners in at least 55 zip codes in houses so damaged by water that each requires tens of thousands — and sometimes, hundreds of thousands — of dollars in repairs.

>Experts have labeled Pennsylvania the epicenter of an industrywide epidemic that has affected sprawling suburban houses, starter homes, and luxury Philadelphia townhouses alike. Properties constructed with materials other than stucco had problems, too. Some houses with water damage were built by billion-dollar public companies. Others, by small, local firms. Some are 10 or 20 years old. Others are brand-new.

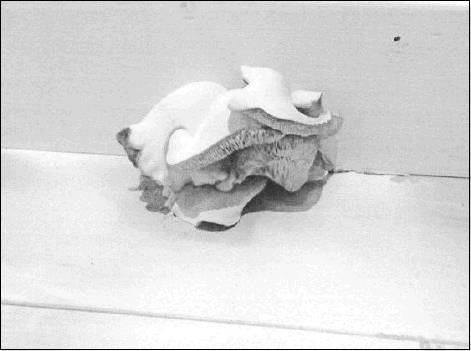

>Several hundred lawsuits filed in the last five years allege that most of these homes contain dozens of violations of the state-mandated building code that ultimately allowed water to drain into both new and renovated homes. Many homes with water damage lack basic weatherproofing materials, inspection reports say. Coats of stucco are often too thin. According to alawsuit by the owners of a $1.96 million Center City townhouse, workmanship was so poor that, even before the family moved in, a mushroom sprouted in the floorboard of their 20-month-old child’s bedroom.

>Even as builders have combated claims, nearly two dozen homeowners said that they were never notified of any potential problem — even as some building executives knew of its extent. Toll’s vice president of construction, Anthony Geonnotti, for example, testified in 2017 that, within slightly more than two years, he had inspected 300 to 350 homes in the region for water intrusion — with roughly 85 percent needing repairs, according to an arbitration hearing transcript filed in court. Countless homeowners have discovered the problems only after it’s too late to bring a claim under state law — with some missing the deadline by just weeks or months.

>The problem has caught the attention of the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s Office and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, which have launched independent investigations. Builders, meanwhile, have been setting aside hundreds of millions of dollars for warranty claims.

>One builder last week, Hudson Palmer Homes, founded by David Cutler of the David Cutler Group, filed for bankruptcy. Cutler in October was found in contempt of court after his company failed to honor settlement agreements with some Chester County homeowners who had water-intrusion claims.

The Inquirer found that in many cases, moisture may have trickled in from day one but loomed undetected for years. Underneath seemingly unblemished exteriors made of different materials — brick, stucco, vinyl siding, stone, fiber cement board, and more — water has damaged everything from window sills to insulation that once puffed like pink cotton candy. In some cases, wooden sheathing is so saturated that it now flakes easily, crumbling into mulch-like chips. Mold, termites, and phorid flies have infested some walls.

Other houses are so water-ravaged that they have become structurally unstable.

Experts say the damage cannot be seen in 80 to 90 percent of cases — meaning other homeowners may unknowingly have the same problem behind their walls. And with roughly 90,000 new single-family homes constructed in Southeastern Pennsylvania since 2001, the extent of the damage in the region may not yet be fully discovered.

Typically, the problem becomes evident only when a neighbor tries to sell — and a moisture inspection returns grim news. House after house gets inspected. Scaffolding goes up. The only fix, experts say, is to strip a building down to its wooden base and rebuild, turning well-manicured neighborhoods into construction sites again.

In the Goldsteins’ neighborhood, for example, nearly onethird of Buckingham Forest’s 198 homes have had their exteriors ripped off and rebuilt anew.

"This is of epidemic proportions. All of these houses built since the construction boom will not last through their mortgage.

Rob Lunny, owner of Lunny Building Diagnostics in Bucks County, who has inspected more than 2,000 homes for water damage since 2013

Some builders who have been contacted — or sued — by homeowners maintain they bear no liability for the problem. In court records, some have pointed the finger at product manufacturers or subcontractors who worked for them. Others say builder warranties for the homes have expired and they can no longer help. One lawyer for Toll has said in court testimony that the damage is “not a Toll issue,” but rather stems from deficiencies in the state-enforced building code at the time.

“Water intrusion-related issues on older, stucco homes are an industry-wide problem in Pennsylvania,” Toll, based in Horsham, said in a statement to the Inquirer. "We have an excellent record of ensuring that these water intrusion complaints are reviewed and resolved.”

Another builder, whose attorney advised him to withhold his name, said he did not become aware of water-intrusion defects until 2015 and has since stopped using stucco on homes because of the complications it has with wooden framing. He said he has offered settlements in the past. Another Toll executive said in court testimony that the company stopped using stucco in Pennsylvania "sometime in 2012, 2013."

More than two dozen builders contacted multiple times by the Inquirer declined to comment, did not respond, confirmed they were in litigation, or said the cases lacked merit and would be defended in court.

Wet homes threaten to erase equity that countless families have accrued and had hoped to pass along to the next generation. Homeowners, then, are left in an unenviable bind: Litigate the problem, pay for it themselves, or live with it in a home they will likely have trouble selling.

“This is of epidemic proportions,” said Rob Lunny, owner of Lunny Building Diagnostics in Bucks County, who has inspected more than 2,000 homes in the region for water damage since 2013.

“All of these houses built since the construction boom will not last through their mortgage.”

One common bond

Some homeowners grappling with water intrusion are single millennials who scrimped for their first home. Many are busy parents, juggling careers and kids. Other are retirees who bought new homes, thinking it would likely be their last.

All of them, however, are bound by one thing: They purchased brand-new or newly renovated homes constructed from builders they trusted.

The fallout has been devastating.

One Bucks County man was forced to quit a job he took in another state because his house would not sell. Another man’s insurance company threatened to drop coverage if he didn’t fix the damage, he said. A stay-at-home mom is searching for work to help pay for legal fees that have ballooned to six figures. And several homeowners said they believe new health issues stem from what’s happening behind their walls.

Out-of-pocket repairs and attorney's fees have erased college funds, retirement savings, and nest eggs, homeowners say. Many worry about financial stability in the years to come.

Take the case of one Montgomery County couple who in 2004 purchased a 4,000-square-foot property from Blue Bell-based Guidi Homes. After learning of a neighbor’s water-intrusion problems across the street in 2016, they sought inspections and repair estimates. Two prices came back: Nearly $219,000, the first company said. And nearly $349,000, said the second, according to a lawsuit.

Or, consider Todd Hagerich, who bought a house built just before the housing boom in Toll’s Cold Spring Hunt neighborhood in Doylestown. He managed last year to pay a little more than $101,000 to repair the problem — but only after taking out a home-equity loan.

And in Chester County, acouple still await the $324,000 that a judge awarded them against Misty Meadows Homes this year after they had to sell their 2004-built, water-damaged property — unrepaired — at a $130,000 loss. The decision has been appealed.

Some homeowners have found victory in court and arbitration hearings. But not always. Judges have sided with builders, too, ruling, in some cases, that homeowners cannot bring claims once the time period allowed by state law has passed. And because so many cases are handled privately, it can be difficult to understand the full scope of the outcomes.

Homeowners are left with one big question: How could the brand-new homes they expected to last a lifetime end up so damaged in just a few years?

State prosecutors and federal regulators wonder that, too. The Pennsylvania Attorney General’s Office in 2016 filed a lawsuit against the David Cutler Group, based in Montgomery County, and launched a “review” into Toll this spring, financial filings show. According to a spokesperson, the Attorney General’s Office has received about 200 complaints from homeowners about water intrusion in the last five years. She declined to name specific builders or comment further.

In addition, the Securities and Exchange Commission investigated Toll and had requested information about the company’s estimated costs to repair water-intrusion claims — which, as of September filings, was around $324 million. Neither Toll nor the SEC would comment on the status of the investigation.

At least four other public companies that build homes in the region — PulteGroup, K. Hovnanian, D.R. Horton, and NVR Inc. — also have disclosed in filings that they have set aside millions of dollars to pay for warranty claims, though some do not mention water intrusion specifically.

The Inquirer examination isn’t the first to point out deficiencies related to stucco — a material that was previously linked to water damage. Yet never before has it been revealed how systemic the damage is in the region, or to what extent other materials — including brick and vinyl siding — can be compromised.

One reason the problem has been hidden in plain sight for years is that many homeowners sign away their right to sue when they buy — and instead are frequently required by builders, including Toll and Pulte, to enter into mandatory arbitration, where records are not public. Other builders who are sued often settle before trial and typically require homeowners to sign confidentiality agreements.

Some builders take on new company names for different projects, making it difficult to track whether a builder has been blamed for construction defects before.

Yet as the number of lawsuits have amplified, experts and building engineers have pegged Pennsylvania, given its wet climate and temperature fluctua tions, as the heart of an industry wide crisis. Other states, howev er, are not immune, including New Jersey and Delaware.

Experts say the problem is a la tent symptom of the 2000s build ing boom, when builders flocked to the suburbs, constructing homes quickly and en masse amid red-hot demand. Now, as many those same builders, and new ones, rush to capitalize on Philadel phia’s current real estate renais sance, observers worry that scores of new homes —and rehabs of ones —could be at risk.

“Quicker, cheaper, faster that’s the mentality,” said Kevin Thompson, founder of the Green Valley Group, a Chester County moisture-inspection company “Guys are not formally trained You can swing a hammer? Great you’re on the job.”

An early concern

From the beginning, Kim Short and her husband, Jim, decided no new construction.

“We always thought that older homes are built better,” Kim said. “We aesthetically just older things.”

But that changed in early 2014 when Kim and her real estate agent stumbled upon a cozy block in rapidly gentrifying Fish town. There, Frank Mazzio

AGA Developers was building sleek, luxury townhouses adorned with gray siding, balco nies, stucco, and brick.

Kim was impressed.

The construction would be envi ronmentally friendly. Early de signs seemed “thoughtful.” Mazzio himself would be on site, Kim said he told her, overseeing from trailer out back. All problems that initially emerged would be cov ered by a one-year warranty.

But one thing gave Jim Short 49, pause when he toured the con struction site later that spring water intrusion.

Mazzio personally assured

Shorts that day that water would not enter their walls, they con tend, telling them it was his priority.

So the Shorts submitted an of fer of slightly more than $450,000

Within months of moving in they noticed something was wrong

Water would pool inside window sills every time rained. A neighbor, Peggy Jack son, noticed her floors becoming damp and stained, she said. When they and others complained, AGA sent a contractor to re-caulk windows — but the leaks continued. The contractor returned. The leaks grew worse.

"Quicker, cheaper, faster — that’s the mentality. Guys are not formally trained. You can swing a hammer? Great, you’re on the job.

Kevin Thompson, founder of the Green Valley Group, a Chester County moisture-inspection company

Inspection reports and lawsuits by seven neighbors on the block now allege that construction defects allowed water to gush into her walls. In the Shorts’ home, a moisture-inspection test showed that some parts of their wall had likely decomposed and developed mold. Paper meant to line the roof, rather than the kind required by the building code, was used on the walls. At Jackson’s, the stucco was not adequately sealed around some pipes, an inspector said, allowing water to trickle in and travel through her walls.

When they reached out again, Mazzio, according to Short, told her: Hire an attorney.

So last year, she and neighbors did. Their agreement of sale required they go through mediation. But, their lawsuits allege, Mazzio “refused to mediate.”

Neither Mazzio nor his attorney responded to multiple requests for comment.

“We had joked with our Realtor it will be straight from here to assisted living,” Short said. She now faces an estimated repair bill of more than $200,000.

“It’s not like we can just pay that,” Short said. “It’s supposed to be a luxury house.”

‘A perfect storm’

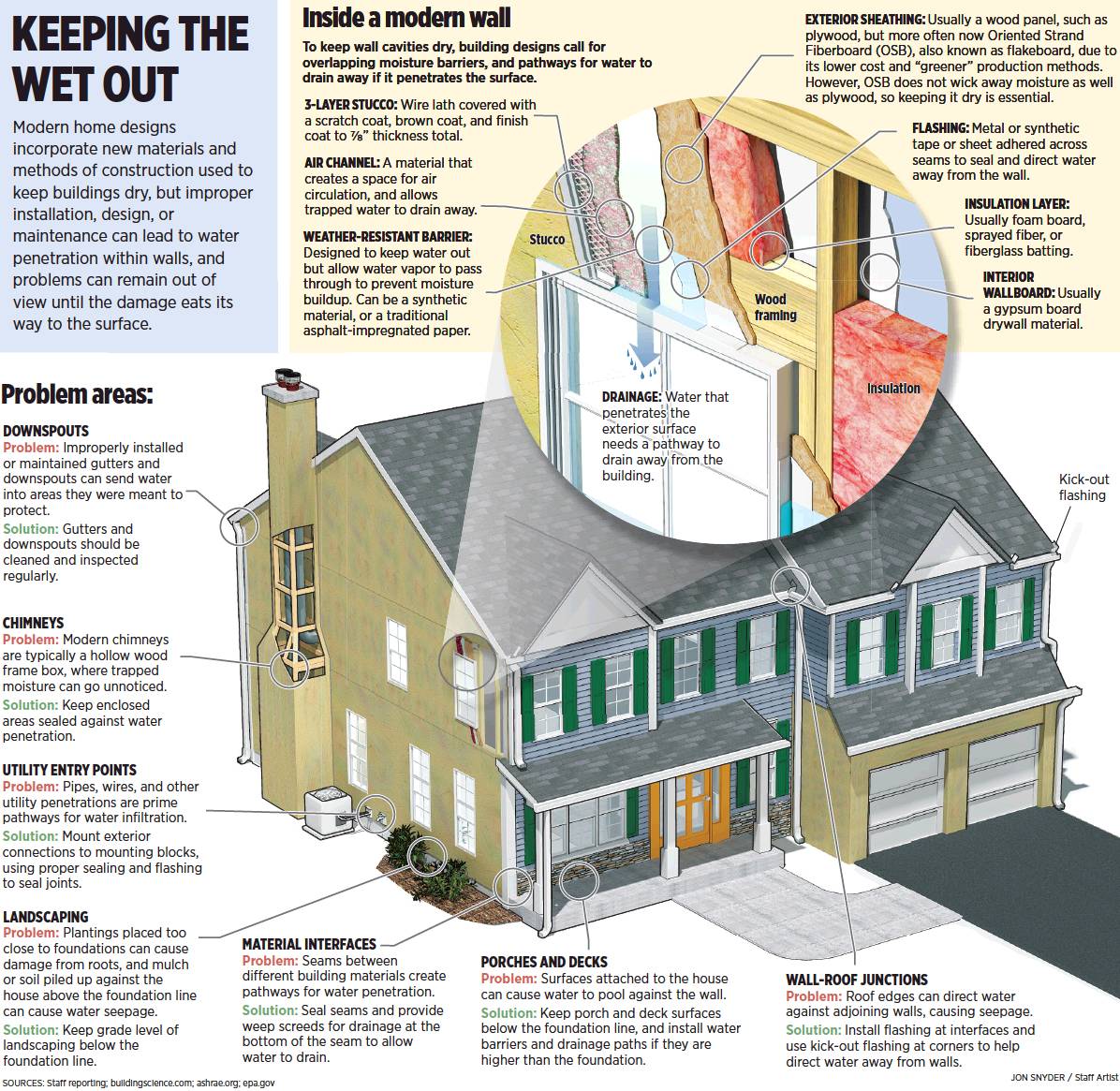

Water has long been an enemy of new construction.

“When I was going through the ranks way back when, people had taught me that the three biggest problems in buildings are water, water, and water,” Joseph Lstiburek, a renowned forensic engineer, said during a presentation last year. “More problems occur because of rain than any other single issue in construction.”

Yet while water has always had the potential to destroy homes, only recently has it done so at such a widespread or rapid clip. Thompson, the Chester County moisture inspector, noticed problems emerge around 2006 — but “take off” in 2010.

It is not unusual for new homes to have small defects. But the sudden avalanche of waterlogged houses originally puzzled observers: How could so many homes built by so many different builders be experiencing the exact same problem at once?

According to Lstiburek, the answer was simple: It was “a perfect storm” — acombination that attorneys now allege came from pressure to build faster, an industrywide switch to lower-cost building materials, and little government and builder oversight. Add to that a climate like Pennsylvania’s, where the average annual rainfall is around 41 inches — and the potential for water damage was that much greater.

Part of the problem, Lstiburek said, is that houses today are built differently than decades ago — and are less forgiving when wet. So when shoddy construction occurs simultaneously, he said, results can be disastrous.

Among the largest differences today is that homes are more energy-efficient, keeping heat and air from escaping. But that can be problematic for a house’s internal walls, Lstiburek said, which need airflow to dry.

And as new technology has ushered in more environmentally friendly and less expensive materials, he added, there’s been one big downside: Many are far less water resistant.

“It’s not that buildings are getting wetter,” Lstiburek said in an interview. “Now, it takes longer to dry.”

‘No one is watching’

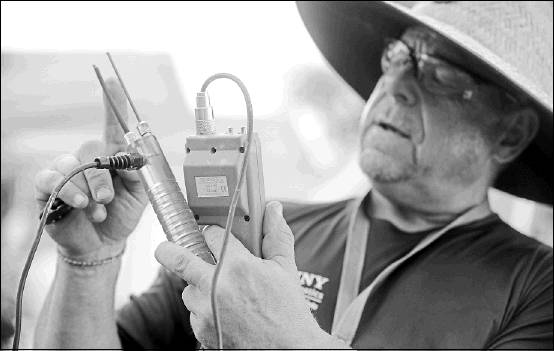

Standing in a Chester County cul-de-sac under a late-summer sun, Lunny, the Bucks County-based moisture inspector, watched as a small construction crew cut the stucco off of a 6,000-square-foot home built by Thompson Homes in 2006.

“Back in the 1950s, a builder would build five or 10 homes. The crew knew each other,” Lunny said. “Here, we build 100, 200 homes at a time.”

Lunny recently became certified as a “third-party oversight” inspector, meaning homeowners can hire him to inspect as crews rebuild water-damaged homes. Even when homes are being re-mediated, Lunny said, he still catches code violations the second time around.

The reason, he believes: little oversight — from builders and government officials.

“The only people with power over the builders are these townships,” Lunny said. “No one is watching and these houses are failing.”

Under Pennsylvania law, municipal code inspectors are required to visit a house multiple times as it is built to check the foundation, framing, and plumbing, for example. Governments can opt to add more inspections if they choose.

Inspectors are not, however, specifically required to check for errors that could lead to water intrusion.

Inspection departments in the suburbs and in Philadelphia said the problem boils down to resources. Asking inspectors to check every layer of a house — known as the building envelope — would be impossible.

“Unless we were to have an inspector on site the entire time as the house was built, it would be difficult to see these problems,” said Jim Kettler, director of building and codes for Buckingham Township, Bucks County.

Karen Guss, spokesperson for Philadelphia’s Department of Licenses and Inspection, said that while no separate inspection is required, “I don’t want to suggest that these kinds of things are not looked at at all.”

Both said the lack of formalized scrutiny does not absolve builders from building to code.

Just 30 miles south of Philadelphia, New Castle County, Del., has put resources toward the water-intrusion problem. After seeing a rash of complaints, the county added three separate building envelope inspections to its required list in 2009, including an exam of wooden sheathing and required house wrap.

The results are difficult to track, but officials in New Castle’s Department of Land Use said complaints have “diminished.”

“[Construction crews] say, ‘This is just the way I’ve done it forever,’ and not think twice about it,” said Mike Connors, assistant land use administrator for the county. “But it’s not one of those things where you do something wrong and it shows up immediately.”

“It’s 10 years down the road when you begin to see major, major issues,” he said. “It goes unseen for so long.”

Sealing the deal

In a Center City office with a view of City Hall, attorney Jennifer Horn, of Horn Williamson, has represented several hundred homeowners against numerous builders since her construction practice started in 2015.

She alleges that builders alone should be held liable for the problems across the region.

“In an effort to get as many homes finished as quickly as possible it appears mistakes were made,” Horn said. “Based on my experience with experts, subcontractors, and builders, I believe the problem is caused primarily by inadequate architectural and construction oversight, as well as builders’ design and construction practices that failed to comply with building code.”

Consider the case of Brian and Anna Mulnix.

Like the Goldsteins, the Mulnixes moved to Bucks County in the 2000s, enticed by Toll’s Buckingham Forest development. It had the schools they were seeking. They thought Toll’s model home was “beautiful.” And with a young child and busy lives, they liked that their next home could be move-in ready.

But it was more than just appearances that convinced the Mulnixes, according to a transcript of arbitration testimony filed in Bucks County Court this year. The promise of quality assurance sealed the deal, Brian Mulnix testified.

Toll had advertised in-house architects and engineers, testimony and archives of the builder's website show. Aproject manager, the website said, would be on site and inside each house “once, twice, three times a day.”

"It’s 10 years down the road when you begin to see major, major issues. It goes unseen for so long.

Mike Connors, assistant land use administrator for New Castle County, Del.

“What that meant was this house should last a lifetime and more,” Brian Mulnix testified in October 2017. It implied, he said, that his house would be “built in accordance with code.”

But when the Mulnixes tried to sell their house nearly a dozen years later, they were surprised by what they found.

In the spring of 2015, a new job opportunity, beckoning Brian Mulnix to Texas, came with a hard-to-refuse offer: If they couldn’t sell their home, a relocation company would buy it.

There was just one requirement — a moisture inspection test.

At the time, the Mulnixes had seen rot around doors and some “black soot-looking staining of stucco,” Brian Mulnix testified in arbitration. But they thought nothing of it. With a little sprucing, they thought, the home they had purchased on Valentine's Day 13 years before would sell in no time.

The inspection proved otherwise: A material known as flashing — pieces of metal that are installed in critical places on a home to divert water away — was installed incorrectly or missing, allowing water to “drain directly into the stucco,” the report said. Their stucco had cracked. A crucial piece of flashing at the bottom of a wall that allows water to drain — a weep screed — was also missing in places, the report said.

“The failure to install any provision at the bottom of any of the walls was a fatalistic mistake,” according to one inspection report — one of many the Mulnixes commissioned — by Frank Hendron, a building science consultant at Northeast Inspection Corp. in Newcastle County. His 2017 evaluation “revealed systemic failures,” he said, that have occurred each year since construction.

Before the Mulnixes hired Hendron, they had reached out to Toll, asking for help after their first inspection revealed some defects.

Toll’s response, he said: There was nothing the company could do to help.

In a statement, Toll said the company denied the family’s claim “because their home was outside the 10-year warranty,” as well as a Pennsylvania state law that allows homeowners to bring claims against builders within a set period of time.

Unable to sell the house, Mulnix quit his job in Texas after eight months to move back home. The couple paid $23,000 for a company to fix the most problematic parts of the home, but the fix did not work. They conducted multiple inspections and sought stucco-removal estimates. They hired Jennifer Horn and requested Toll’s help again.

When the company issued a second denial, they went to arbitration.

After seven days of testimony from the Mulnixes, Toll executives, subcontractors, and others, retired Philadelphia Judge William Manfredi found that Toll’s architectural drawings “did not comply with applicable laws and regulations.” No testing was performed prior to sale, he said. Toll had “failed to design and construct the home without defects.” And in the end, he added, there was “destroyed sheathing and compromised framing … that impacts the structural integrity of the home.”

He awarded the Mulnixes $407,187.59, including more than $100,000 of attorney's fees.

Toll appealed. A Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas judge sided with the Mulnixes.

Toll appealed again. The case is pending before the Superior Court of Pennsylvania.

All the while, attorney’s fees for the Mulnixes keep on ticking up.

“We’re a …family paying bills — they know that they have much deeper pockets to starve us out,” Brian Mulnix said in an interview. “This is a debt that we will owe for 15 more years, for 30 more years, and we’re both in our 50s now.”

“It’s basically like another mortgage.”

The rules for repairs

Toll declined to say how many water-intrusion claims it has received in Southeastern Pennsylvania in the last few years.

But arbitration testimony for the Mulnix case offers some clues. Geonnotti, vice president of construction at Toll, testified in October 2017 that one subcontractor for Toll had remediated “around a hundred” homes, including those in Buckingham Forest, Upper Mountain Estates, Overlook at Newtown, Plum-stead Chase, Highlands at Chapman’s Corner, and Regency at Northampton — all developments built since the 2000s in Bucks County.

Toll said in its statement to the Inquirer that the company offers to repair homes that are less than 12 years old — a policy that aligns with a Pennsylvania state law that allows homeowners to bring claims against a builder within 12 years, and in some cases, 14 years, after a home is built. The company did not respond to a question about when that policy began.

“If a home with stucco-related or water intrusion issues falls within Pennsylvania’s 12-year limitation and repairs are needed, Toll Brothers has committed to repair it,” the company said in the statement.

Some homeowners have disputed Toll's assertion and have said they were denied when their homes were less than 12 years old.

Others wonder: If builders knew about this problem years ago, why did no one tell them something could be wrong with their homes?

" T h e p r o b l e m isn't just how many cases [attorneys] are handling," said Peter Bryant, of Bochetto & Lentz, who represents several dozen homeowners in these cases. "The problem is, how many people are left out in the cold because of these latent defects that haven't shown up until 13 years, 14 years or later?"

It’s something that the Gold-steins in Buckingham Forest think about often. They had seen rot around their front and back doors and ultimately replaced them in 2013. Had Mitch Goldstein known it was a sign of a bigger problem, his home — just 11 years old at the time — would have still been new enough to bring a claim under state law.

Instead, it was not until late 2016 that Goldstein began to hear whispers about water damage and see scaffolding rise. By that time, his home was more than 14 years old. He was out of luck.

So this year, he hired a construction company to rip the stucco and stone off his house and replace it with fiber cement board and some stone. The price: slightly more than $60,000.

“They call themselves a luxury brand … but there’s nothing luxurious about this,” Goldstein said, sitting in his kitchen as crews drilled and hammered, shaking the walls of their house.

Since Goldstein discovered water intrusion in his home, he has passed out flyers, created a website, and contacted lawmakers in Harrisburg.

One of them, Rep. Bernie O’Neill (R., Bucks), responded by proposing legislation.

In 2017, O’Neill, who is retiring in January, introduced two bills: House Bills 1831 and 1833. The first would extend the amount of time a Pennsylvania homeowner has to file a lawsuit by three years. The second would require builders to notify homeowners of construction defects once they become aware of the problem.

O’Neill’s bills are awaiting action in the House’s Local Government Committee, where they have sat — untouched — since they were introduced.

In the meantime, residents in the Philadelphia region say they are doing everything they can to get by.

“My neighbor across the street, he’s got a daughter in college and he said, ‘I’ve got to get her through school before I can do [repairs],’ ” said Hagerich, the Toll homeowner in Bucks County who took out a home-equity loan to pay for repairs. “My daughter’s in high school. … We’re not contributing to college, which is highly concerning.”

“I planned to put a roof on; I planned to replace the furnace,” Hagerich said. “I did not plan to replace the sides of my house.” cmccabe@philly.com

215-854-2507 @mccabe_caitlin earvedlund@phillynews.com

215-854-2808 @erinarvedlund

Staff Writer Erin Arvedlund purchased a Toll Brothers home in 2017 in

Philadelphia’s Naval Square development.

"They call themselves a luxury brand … but there’s nothing luxurious about this.

Mitch Goldstein, sitting in his kitchen as crews drilled and hammered, shaking the walls of his house