RECYCLING

It Doesn’t Pay

Phila. used to make money off plastics and metals that we tossed. Now, it must pay.

By Frank Kummer STAFF WRITER

A truck loaded with curbside recycling opened its giant maw and five tons of plastic, cardboard, and metal spewed to the ground next to a 25-foot-high pile of recyclables recently dumped at the Republic Services facility in Philadelphia.

By the end of the day, the Grays Ferry location had received up to 500 tons of recyclables — processed at a rate of 25 tons an hour. It’s astaggering amount to move, sort, bale, and ship on a daily basis. About 20 percent goes to landfills because of non-recyclable items such as hoses, rigid plastic containers, and pizza boxes mixed in.

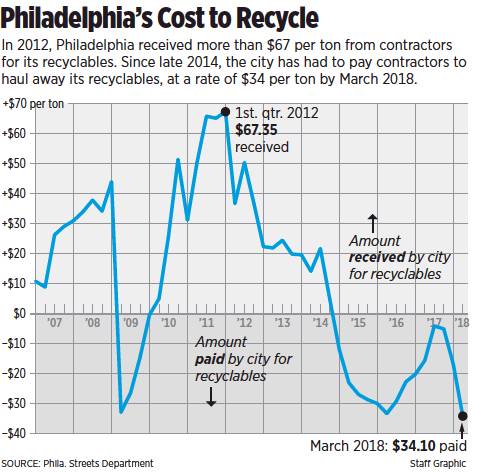

Five years ago, Philadelphia was getting paid good money by contractors for recyclables — about $65 a ton.

By last year, it was paying $4 a ton just to get rid of it. Now, it’s paying $38 a ton.

The change has not gone unnoticed. That plastics and other scraps meant for recycling are ending up in landfills — at a cost to taxpayers — was an issue raised through Curious Philly, our new question-and-response forum that allows readers to submit questions about their community in need of further examination.

“We made the argument that recycling was so much cheaper, but that’s getting closer to not being true,” said Nic Esposito, director of Philadelphia’s Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet. “That’s scary.”

City taxpayers will likely chip in about $2 million to cover the increase this year, according to budget figures.

If the trend continues, recyclables could become just as expensive to get rid of as ordinary waste, which means items once recycled will go straight to landfills, undoing decades of work to get residents and businesses to go green. (It costs about $63 a ton to dispose of waste at a landfill.)

The cause of what many call a recycling crisis began in 2013 when China shifted away from its role as the world’s major recycler. As part of its crackdown on pollution, China began demanding ever purer loads of recyclables. Previously, Chinese facilities might have accepted loads that were 10 percent or 20 percent contaminated by non-recyclable plastics or paper and cardboard that was wet or dirty.

But the last year has been particularly painful for recycling. China is now demanding that loads be no more than half a percent contaminated, and contain no mixed paper (such as office paper mixed in with newspaper) - an impossible standard to meet for most municipalities. In Philadelphia, as much as one-fifth of each load might be contaminated.

Recycling companies had to figure out how to unload millions of tons elsewhere. Recyclers have been able to find some domestic and overseas markets such as Vietnam and India for plastics, but those countries are now overwhelmed.

China distressed markets even more when it refused all recycling from May 4 through June 4. Recyclers had to stockpile loads. “We put so many eggs in the basket in China,” Esposito said.

Philadelphia and many municipalities use contractors to process single-stream recycling. Contractors are now appealing to residents to use less plastic and be cautious of what they put in recycling bins.

The goal is to get loads as pure as possible.

“We weren’t exporting plastic to China in recent years,” said Frank Chimera, a senior manager with Republic Services, the city’s contractor to process recycling. “But we were exporting mixed paper, cardboard. Prior to all this we were sending about 60 percent to China. As of March 1, we stopped sending anything.”

The company has had to stockpile mixed paper loads at times until it found domestic buyers. Some loads are being shipped to Indonesia and India. But that poses other problems.

“The cost to ship is greater than the value of paper,” Chimera said.

The crunch has caused turmoil for recyclers, who have always borne the brunt of processing but made up for it by selling sorted recyclables as a commodity on the open market.

“Recycling economically does not make sense right now,” he said. “So companies like Republic are propping up the recycling industry.”

Plastic bags a big problem

On Tuesday, Chimera stood with Tim Spross, also of Republic Services, high atop a steel platform where thousands of pieces of paper and cardboard rushed down a conveyor belt.

Workers scrambled to pick out as many plastic bags, dirty cardboard, and non-paper items from the swift-moving stream. Plastic bags, almost ubiquitous, are especially onerous because they clog machinery, forcing lines to shut down.

“Plastic bags are one of our biggest problems,” Spross said.

He walked to a wall of bales of non-recyclables that were removed from the trucks and conveyors. The wall ran 10 feet tall and 50 feet long. All of it will go to a landfill.

Contamination drives up costs

John Hambrose, a spokesman for Waste Management, which contracts with other municipalities, says his company is experiencing similar issues. Waste Management has a recycling processing facility on Bligh Avenue in Holmesburg.

Hambrose said the situation is not at the point where recyclables are going straight to landfills. But he said costs are being passed down to municipalities and, ultimately, taxpayers.

“In the last few months, we have been working with municipalities,” Hambrose said. “We’re evaluating the quality of materials they are sending us. When we find high levels of contamination, that’s when additional fees may incur.”

Contamination occurs when residents either don’t know what’s recyclable or simply don’t care.

Food waste gets tossed in with plastic, contaminating an entire load. Liquids left in bottles drip down, ruining paper. Pizza boxes stained with grease are unusable. Heavy rigid plastics, such as crates and bread carriers, also get tossed in, although they are not recyclable. Some residents toss in dirty diapers.

“If there’s too much trash in recycling, then it’s basically all trash,” Ham-brose said. “You’re really trying to do this efficiently and make a business out of it. But contaminated loads drive up your costs. At the end, you’ve got low commodity values. So we’re really caught at both ends.”

Recycling companies such as Republic Services and Waste Management are sometimes locked into longer-term contracts with municipalities and have to eat the additional costs.

For example, Camden County has a multiyear contract with Republic Services that locks in a cooperative agreement with 37 municipalities to pay $5 a ton to unload recycling — $33 less per ton than Philly.

“Other than the fact that we were getting money for recyclables, and now we are paying money, it hasn’t hit us as hard as other municipalities because of our participation in the co-op,” said Thomas Cardis, business administrator for Gloucester Township in Camden County. “If we weren’t in that bid, then we would have some serious concerns right now. But, ultimately, we’re concerned we will eventually be susceptible to the market.”

Back at the Republic Services facility in Grays Ferry, workers were sorting through the just-delivered load from the recycling truck. They loaded the non-recyclables into carts and wheeled them to a 12-foot-high hill of debris waiting to be sent to a landfill. As soon as workers clear the pile, it starts to rise anew. fkummer@philly.com

215-854-2329 @frankkummer

Five years ago, Phila. was getting good money for recyclables: About $65 a ton. Now, it pays.