Sharing their stories

Activists, kin want to tell the world what happened in Carlisle.

By Jeff Gammage STAFF WRITER

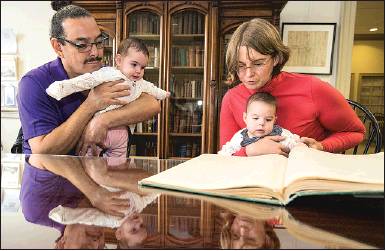

CARLISLE, Pa. — Daniel Moya and Anna Naruta-Moya came 1,600 miles from New Mexico, their twin baby girls in tow, on ajourney that was part family pilgrimage and part public mission:

To help tell the world what happened here at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, and at others like it, where native children were shorn of their names, languages, and religions, and submitted to a cultural genocide that still tortures tribes and families today.

“There’s no sense of healing, because there’s a lot of information that’s missing,” said Moya, a Tewa artist and researcher.

His wife directs the new Indigenous Digital Archive, an effort to find and share unknown documents on Indian boarding schools and meet a growing demand for information about a destructive and damaging era.

“There’s a surge now among people who grew up hearing things — or not hearing things,” said NarutaMoya, who previously worked at the National Archives and the Hoover Institution at Stanford University.

The Indigenous Archive joins a painstaking effort — led by Dickinson College and the Cumberland County Historical Society — to speed the transfer of primary-source records onto the web, to solve the biggest dilemma for researchers in the American West and in Europe who want access to big Eastern collections: distance.

On Saturday, the couple joined about 200 university scholars, American Indian activists and writers, descendants, tribal leaders, and even an Olympic gold medalist at the historical society’s Carlisle Journeys conference, held every two years to investigate the still-emerging story of the nation’s first federal off-reservation boarding school. People came from as far away as Canada and England.

The topic: the complicated legacy of Carlisle’s superior athletic programs, which included the legendary Jim Thorpe. Carlisle’s defeat of bigger, wealthier schools, particularly in football in the early 1900s, proved to the country that Indian athletes were the match of any, but also served as a propaganda tool to help administrators raise money and recruit students.

“The Carlisle story is the story of Indian people, in many beautiful and tragic ways,” said Billy Mills, the Oglala Sioux runner who in 1964 won Olympic gold in the 10,000-meter race, and remains the only American to accomplish that feat.

Reclaiming remains

Amanda Blackhorse, a prominent Navajo activist from Arizona, wore traditional clothes and opened her remarks in her native language — to honor the Carlisle students who were forbidden to do so. Oneida Nation representative Ray Halbritter, whose grandmother attended Carlisle, said Indians both decry the harms inflicted at the school and celebrate the against-the-odds achievements of its athletes, male and female.

The conference comes at a contentious moment, as American Indians battle in court to stop Washington’s NFL team from using the name “Redskins” — a dictionary-defined slur — and on the ground to block construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. It’s particularly fraught in Carlisle, as tribes demand the return of the remains of students buried in the school cemetery, now contained within the campus of the Army War College.

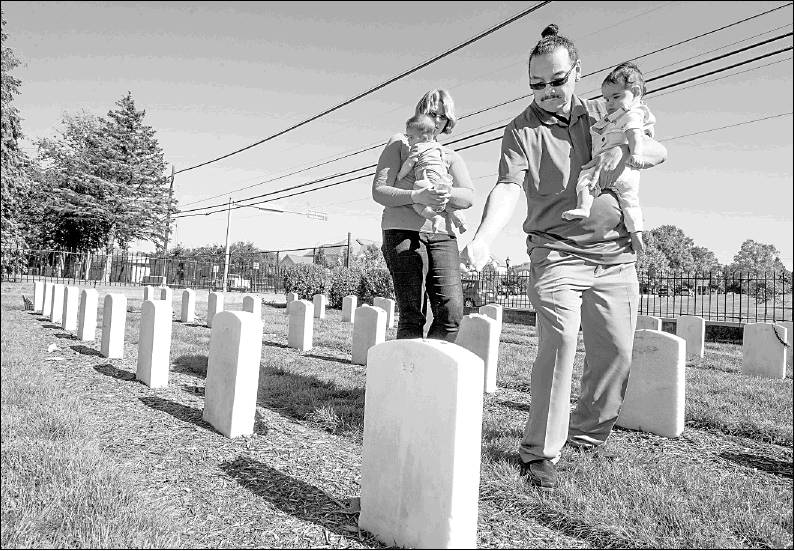

Nearly 200 children lie in neat graves, lost in a turn-of-the-century experiment in forced assimilation. Now the Rosebud Sioux of South Dakota seek the return of 10 children, Alaska nations want 14, the Northern Arapaho of Wyoming seek three, and other tribes are considering action.

Army officials who control the cemetery have pledged to return remains, though some Indians harbor doubts.

Many conference attendees planned to visit the cemetery, to pray and to leave offerings, and organizers added an extra Sunday tour of the school grounds.

“I’m always amazed there is such interest,” said Ory Cuellar, 74, an Absentee-Shawnee tribe member whose father, Andrew Cuellar, was the school’s last living graduate before his death in 2002 at age 103.

Tokens of candy

Carlisle was established in 1879 by former cavalry officer Richard Henry Pratt, and backed by Christian reformers and a federal government eager to “civilize” Indians — seen as more humane and less expensive than killing them outright. Pratt’s motto, “Kill the Indian, Save the Man,” became the guide for dozens of similar, military-style schools built across the United States and Canada.

On Thursday, after arriving from Santa Fe, Moya and Naruta-Moya paid respects at the cemetery, leaving tokens of candy at the graves. His family ties to Carlisle go back more than a century.

Moya’s great-grandfather Antonio Tapia, of the Pojoaque Pueblo, initially was sent to poor New Mexico boarding schools, but in September 1893 managed to get transferred to Carlisle, where he heard conditions were better. He left in March 1901, one of the few students to ever actually graduate from the school, which closed in 1918.

In New Mexico, Tapia became a teacher and translator for native, Spanish, and English languages. His daughter, Daniel’s grandmother Feliciana Tapia Viarrial, was sent to boarding school at age 5 in 1909. She stayed until she left to get married in 1922.

She raised Moya, but rarely spoke of her school years. He knows she “ate soap” — a common punishment for students who dared speak their native tongue.

Today, former boarding-school students have shared piercing tales of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse — pain that has rippled through families and is evident, researchers say, in the alcoholism and drug abuse that plague tribes.

“I call it ‘current traumatic stress disorder,’ ” Moya said. “It’s more than just what happened with my great-grandfather and my grandmother.”

The Indigenous Archive initially will focus on New Mexico schools, but there’s always overlap.

Thrift-store find

Recently, for instance, Naruta-Moya examined a batch of documents that were retained by a federal Indian Agent in New Mexico — and ended up in a thrift store. In one, an 1899 letter from Pratt, the superintendent is boastful and brusque, pleading and demanding that more Pueblo children be sent, insisting that the entire boarding-school system “hinges materially on the success of Carlisle.”

“Have you not a small number of exceptionally good boys and girls to send?” he wrote. “If you should by chance have a sturdy young man anxious for an education who is especially swift of foot or qualified for athletics, send him.”

That letter probably hasn’t been seen in modern times.

“Our goal is to access all that information, put it online, and make it accessible to every reservation, every Indian,” Moya said. “Every Indian across the globe.” jgammage@phillynews.com

215-854-4906

@JeffGammage

“ The Carlisle story is the story of Indian people, in many beautiful and tragic ways.

Billy Mills, Oglala Sioux 1964 Olympic gold-medal runner