POST IN-DEPTH THE IMMIGRATION DIVIDE

Jupiter has deep ties to Guatemalan town

Just about everyone in Jacaltenango knows someone in Jupiter.

By Olivia Hitchcock | Palm Beach Post Staff Writer

JACALTENANGO, GUATEMALA — Marcos Cota Diaz didn’t dream of trimming bushes under the South Florida sun, nor did he imagine his baby girl would learn the sound of his voice from international phone calls.

But in 2001, the Guatemalan native felt stuck. He yearned to put a roof over his family’s heads and his children through school so he did what many in his hometown of Jacaltenango with a dream do.

He went to Jupiter.

For years he lived in fear of deportation while he worked “a little of everything,” he said, sending each penny he could back to his wife and young son and daughter in the mountainous northwest Guatemala town of Jacaltenango.

Cota Diaz didn’t want to be in Jupiter, despite its “sister city” relationship with his hometown. He wanted a shot at a better life.

For decades Guatemalans have looked north, particularly to South Florida, for opportunities. The first waves of migrants came fleeing the country’s civil war that raged from the 1960s through the ’90s. Now immigrants’ plights are increasingly economic.

When asked about President Donald Trump’s push for a wall along the Mexico border, some who made that trek — days in the desert, little water, human bones paving the way — just laugh.

A wall wouldn’t have kept them out.

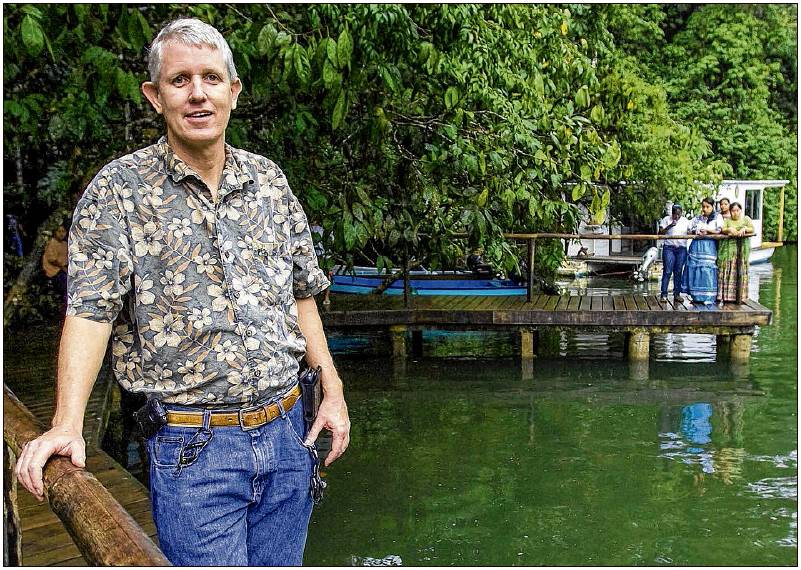

A “virtual wall,” though, one that plugs the holes of Guatemala’s economic woes pushing a flow of immigrants north, may keep them home, argues Steve Dudenhoefer.

Decades ago the Jupiter High School graduate worked alongside Guatemalan immigrants as they trimmed lawns and maintained golf courses in Palm Beach County. He couldn’t quite grasp why they had come so far for seemingly so little.

So Dudenhoefer sold his Jupiter-based landscaping business and went to Guatemala. His goal?

“To give Guatemalans the right not to migrate,” Dudenhoefer said.

A reason to stay in Guatemala

For 25 years, Dudenhoefer has guided a vocational school, Ak’ Tenamit, in eastern Guatemala.

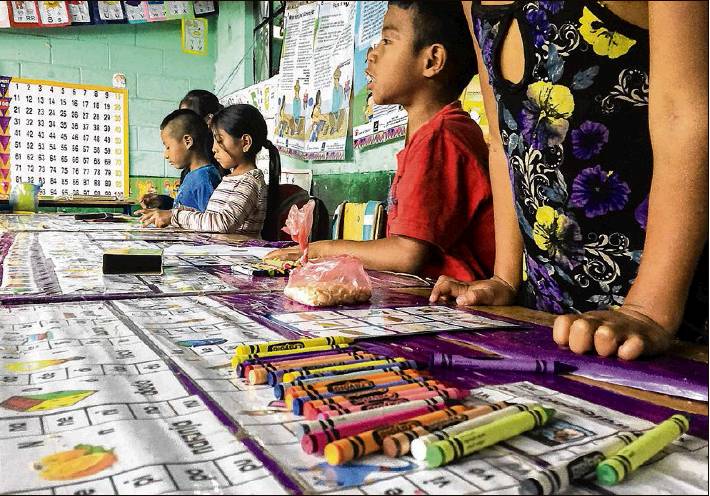

Limited access to education beyond the sixth grade and a lack of money for basic school supplies, uniforms and transportation mean about 2 million school-aged children in the country of 16 million aren’t in a classroom. For Ak’ Tenamit’s 500 students, those costs are covered thanks in large part to Palm Beach County donors.

“Most of these guys don’t want to be (in the United States),” said Suzanne Cordero, who helps raise money for Ak’ Tenamit. Cordero, a Guatemala City native, moved to Jupiter 25 years ago. “I see (the school) as a solution to the immigration problem, not the solution but a solution.”

Hope for a

Guatemalan mother

That “virtual wall” Dudenhoefer wants to build kept Maria Rosenda Cruz Ixtazuy, a young mother of two stuck in an abusive relationship, from joining thousands of other Guatemalans in the trek north.

For years she had struggled to provide for her young daughters. They would both need shoes, she recalled, but she could afford only one pair. One would have to go without.

“If I go,” she asked herself, “who will care for my girls?”

Cruz Ixtazuy, now 28, stayed in Guatemala because she found work with Education and Hope, a program based in Quetzaltenango, the country’s second-largest city, that provides hundreds of students with the opportunity to stay in school and mothers such as Cruz Ixtazuy the chance to make a living.

She is an administrator at the project, as well as a cook and a teacher. Her two girls attended after-school programs there and received scholarships to pay for school-related costs.

“I have my whole life here,” Cruz Ixtazuy said.

Jupiter: So familiar, so far away

Walking along the rocky roads paving Jacaltenango, 11-year-old Katrina Marisol Diaz Silvestre pointed to her fingers as she counted the places she knows in the United States:

“Los Angeles, Nueva York, Disney, Jupiter ...”

Marisol has never been to the Palm Beach County town, but say “Jupiter” to her and she will nod in acknowledgment. Everyone in Jacaltenango knows Jupiter.

Marisol imagines the wealthy town by the sea as an extension of her home among the Sierra Madre Mountains. Jupiter — she paused for a dreamlike “ah” — is where her aunts, uncles and neighbors have gone in search of something more, “to better their lives,” her older brother, Eduardo Antonio, chimed in.

Though exact figures of how many have left Jacaltenango for the States are hard to come by, just about everyone in that northwestern Guatemala town near the border with Mexico seems to be related to someone who has.

Money those immigrants send from the States to Guatemala makes up about 10 percent of the Central American country’s gross domestic product, according to a recent New York Times article.

The cost of a better life

Eduardo and Marisol have grown up surrounded by the spoils and strains of that money in Jacaltenango. When they see their friends get new phones, for example, they know that comes at the cost of an absent parent.

And as they watched their grandparents’ home grow next to theirs in the center of Jacaltenango, they knew their grandmother was inside longing for her daughter each of the seven years Nancy Diaz was in Jupiter.

“It’s not just hard,” said Diaz, who has since returned to Jacaltenango. “It’s sad.”

Diaz doubts her family could have opened the fertilizer store that now is their main source of income if she hadn’t gone north. At 23 she was frustrated at futile attempts to find work in Guatemala, and in 2003 she decided enough was enough. She went to the States.

Diaz was deported twice on her trek through Mexico into the States, she said. On the third time, though, she made it. Once in the U.S., Diaz spent days curled under the seats of a van headed for Jupiter. Four years, she told herself — that’s how long she would stay.

Four years quickly turned to seven as she waited tables, cleaned homes and scrubbed floors at hardware stores.

“I went there with the mindset of working,” she said. She wasn’t there to start a new life; she went to improve the one she had.

Seven years later she learned she was pregnant, and decided it was time to go home.

Coming home to Guatemala

Marcos Cota Diaz could bear only five years away from his family. His daughter, his youngest, was 2 years old when he left Jacaltenango. To her, he was just a voice on the phone.

“She called and asked, ‘Can you visit for a while? I just want to meet you,’” Cota Diaz recalled. When he returned, his wife pointed at him. “That’s your dad,” she whispered to their daughter.

Cota Diaz spent more than a year trying to find work in Jacaltenango while he reacquainted himself with his kids and now unfamiliar town.

“But here I am with my family,” Cota Diaz said from behind his desk at the store he manages.

Family also brought Luis Miguel Cholotio Garcia back to Guatemala, even though, after seven years in Florida, English came easier than Spanish or his native tongue, the Mayan language Tzutujil. He had grown accustomed to the comforts of the United States — paved and unlittered roads, recycling bins — after living in Jupiter from age 18 through his mid-20s.

He returned to San Juan La Laguna along the shores of Lake Atitlan because his family needed him.

He twice traveled back to the States on a tourist visa. Once was to attend an event at El Sol Neighborhood Resource Center in Jupiter, where he had taught English classes. The second time he boarded a plane heading north he didn’t make it out of the Atlanta airport. He was deported back to Guatemala because authorities learned he had previously lived in the States without papers.

“And that was the end of the American dream,” Cholotio Garcia said.

The 27-year-old now teaches English in Quetzaltenango so he can pay for pre-law classes at a nearby university.

“It’s just so, so different,” Cholotio Garcia said of Guatemala.

Cholotio Garcia graduated from Jupiter High School, he said, and earned an associate degree from Palm Beach State College. Students, even teachers, in Guatemala don’t take education as seriously as those he studied with in the States.

“I still haven’t learned how to feel comfortable (in Guatemala),” Cholotio Garcia said.

Building opportunities in Guatemala

Steve Dudenhoefer wants to give Guatemalans such as Cholotio Garcia a reason to stay.

In the 1980s, as Guatemala’s civil war raged on, a young Dudenhoefer traveled the country, looking for where he could help. He landed in an orphanage in the Rio Dulce area, a river valley among a protected land in eastern Guatemala

He traveled by boat along the river and distributed food to the Mayan village leaders, forging relationships as he went.

When the U.S. cut off the aid to that area, those leaders turned to Dudenhoefer for help. He agreed to look for resources, as long as they drove the program.

Thus Ak’ Tenamit was born.

The vocational boarding school started with 12 boys. Twenty-five years later, it has grown to 500 students who travel from across the country to attend. At Ak’ Tenamit they are fed, housed and taught by a market-driven curriculum designed to help them find jobs. By the time they finish high school, they have completed 3,000 hours of work experience in fields such as ecotourism, community development and restaurants.

The Palm Beach

County connection

Riccardo Boehm, president of the Palm Beach Rotary Club, has volunteered at Ak’ Tenamit for years, teaching CPR classes and constructing new buildings. The 77-year-old retired professor sees it as a means to curb illegal immigration.

“I think it’s better for them to stay there rather than to come here if there are jobs that pay,” said Boehm. “We should support programs that make wherever they are prosperous.”

More than 80 percent of Ak’ Tenamit’s graduates leave school with jobs.

Compare that to the rest of the country’s high school graduates — only 12 percent graduate and have jobs. To find work, then, many go north, Dudenhoefer said.

Dudenhoefer has seen the success of the job-focused curriculum and wants to share it with schools throughout the country. First on his list is northwestern Guatemala, home to most of the country’s migrants to the U.S. and Jacaltenango.

The Guatemalan government covers about one-third of the Ak’ Tenamit’s operational costs. Another 20 percent comes from grants, and the rest — nearly half — comes from donations, many from Palm Beach County.

They’re not from Guatemalan immigrants living in the county — “they already give so much,” Dudenhoefer said, nodding to the money immigrants send back. They are like Boehm, a Palm Beach resident, and Catholic parishioners from across the county.

One of the school’s first donors was Dudenhoefer’s father. The younger Dudenhoefer asked his dad for financial support as the school started. That request turned into the Guatemala Tomorrow Fund, located in a Jupiter office filled with pamphlets, pictures and thank you notes addressed to the people who donated a combined $400,000 last year.

Suzanne Cordero, the fund’s executive director, is in the middle of planning the school’s 25th anniversary celebration scheduled for Nov. 3 and 4 in West Palm Beach. Its goal is twofold: to bring in money and to let people know the Guatemala Tomorrow Fund exists.

“I really feel that everyone who lives in this area has been touched by a Guatemalan,” Cordero said. “Even if they don’t realize it.” ohitchcock@pbpost.com