Proposed fence in Valley shows challenges of building ‘wall’

Angry landowners, rugged terrain get in way of Trump effort

By Lomi Kriel STAFF WRITER

A Border Patrol truck powered past a stretch of steel bollard fence, built a decade ago on top of a fortified flood control levee snaking along the winding Rio Grande River.

Muddy footprints caked parts of the concrete embankment where migrants had tried to scale it, and a branch used to hook a ladder to the top had been flung to the ground. Then the fencing stopped. The truck swung on to a dirt road on the levee. The government plans to add an 18-foot fence here, alongside a 150-foot-wide clearing for agents to patrol past the thick cenizo brush, in which migrants often slip through undetected.

The new fence would slice through the home of Fred Cavazos, who has lived and worked on these 77 acres extending from the river all his life. He has looked at the satellite image showing how the fence would cut him off from his beloved cattle and riverfront so many times but even now — especially now — it fills him with rage. A federal judge ruled just last week that the government could enter his property within 72 hours to survey it for the structure.

“This thing won’t work,” Cavazos said. “They’ll find a way to get over it. So why should I give up my home?”

More than 1,700 miles away in Washington, D.C., President Donald Trump had threatened a government shutdown if Democrats did not agree to another $5 billion to fund a wall, his signature campaign promise that he vowed Mexico would pay for. He falsely stated that “tremendous amounts of wall” had already been built, when just $1.57 billion has been appropriated, generally for bollard fencing such as what is slated to slash through Cavazos’ land.

This stretch of the Rio Grande Valley is the nation’s busiest illegal crossing point, but it also poses the greatest challenges to building a fence. Certainly here, no one seriously mentions a wall. Much of the region is rugged and either privately owned or under environmental protection, and there are doubts about whether such a structure would make asignificant difference.

The Cavazos family was the last of 29 landowners to hold out against proposed fencing in Mission. The property has been in the family for decades, one of the few remaining chunks of what was once a Spanish land grant of more than half a million acres. In the 1760s, their ancestors owned about a third of the Rio Grande Valley, but over the years it has shrunk through taxes, land grabs and sales.

In 2006, Cavazos’ cousin, Rey Anzaldua, fought President George W. Bush’s administration when it proposed fencing further south, in Granjeno, that cut through his family home. Officials eventually agreed to build it just beyond, but the family forfeited dozens of acres.

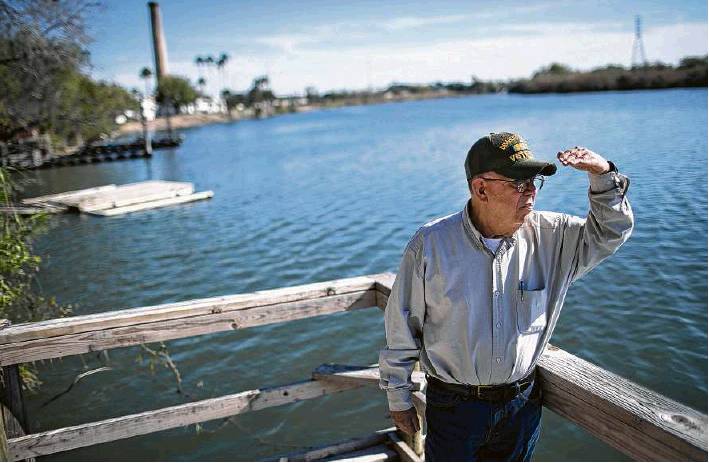

“We keep losing land,” said Anzaldua, a 73-year-old retired Customs and Border Protection officer and Vietnam veteran.

Now he was helping his cousin fight the government, so far unsuccessfully. This section of fence, for which construction is slated for February, would start at Cavazos’ property, extending about 6 miles north.

It would cut off his 30 riverfront tenants — including three Border Patrol agents — who make up his annual income. And it would complicate access to the 69-year-old’s favorite fishing spot. Cavazos uses a wheelchair, and it is not clear where the government would install a gate or when they would build a road to reach his property from wherever the entrance may be.

“If he’s not able to come down here, I don’t think he would have very much left to live for,” Anzaldua said.

A help to Border Patrol

Acting Rio Grande Valley Border Patrol Chief Raul Ortiz understands there is “hit-and-miss” support for the fence in this community. But the way he sees it, looking at the river from the levee splitting Cavazos’ property, it is worth the sacrifice.

“That’s a scout,” he said, pointing to a figure on a tin roof barely visible in the brush across the river. “There is very little technology here, no patrol along the river. When they make it this far, it’s a foot chase through this thick brush to pick them up.”

Even if cameras or agents spot migrants crossing the river, Ortiz said the closest officer is usually 350 yards away on this levee, the nearest public land. A fence would buy agents time.

“It would give us an opportunity to respond,” he said. “People say, ‘Well, does a wall work?’ I can prove it in my own sector.”

The 55 miles of existing fencing from 2006 cuts through the eastern part of his sector, past Brownsville and Harlingen — an area that Ortiz said now makes up just 6 percent of the region’s illegal traffic. Most apprehensions are in Hidalgo and Starr County to the west, which largely remain unfenced.

But the chief acknowledged there is a greater problem which no fence, or even wall, would fix. Border Patrol agents in this region apprehend on average about 680 migrants a day, though two-thirds are mostly Central American families and children turning themselves in. They are not running, but asking for asylum.

“The only thing that will deter that is some sort of legislation, whether it’s repatriating them quicker or efforts like capacity-building in El Salvador,” Ortiz said. “That’s all Congress.”

Mexican cartels, who control access to the river from Reynosa, have wised up, he said, to how long it takes agents to process families. Smugglers are increasingly forcing such migrants to cross in remote areas to distract agents. That provides cover to bring over single adults — who have few of the same legal protections afforded families with children — a little further away.

As if on cue, about a dozen families appeared from the thorny brush, walking toward the Border Patrol truck. Herzon Diaz and his 6-year-old daughter had come from Honduras, where he said violence had made it “just impossible to live.” They both had a cold from the journey.

Katarina Guachiac, an indigenous Guatemalan who spoke little Spanish, had traveled with her 6-year-old to join her husband, who works at a car wash in New York. Martha Livida was with her 10-year-old daughter, having fled El Salvador after gang members forced her to pay $15 of the $40 she earns each day.

“Check for ticks,” a Border Patrol agent instructed. “Take off your shoelaces.”

Another 10 families materialized, and agents said about seven more were further down. The migrants placed all their possessions into Ziploc bags and Merin Rivera handed her 4-month-old baby to a boy next to her so that she could remove her earrings.

She had heard Trump didn’t want them to come, but the 24-year-old said she didn’t understand why or know anything about his policies. She looked exhausted and, taking back her baby who had begun to wail, said the 10-day journey from Honduras was grueling. But it was not nearly as hard as leaving her mother, who is dying of cancer.

“I had no choice,” Rivera said, wiping away sudden tears. “They were threatening me, the gangs.”

The chief said it would take these six agents several hours to process the approximately 40 migrants and transport them to a holding facility. From there, most would be quickly released with GPS-enabled ankle monitors to pursue their immigration cases in civil court. Federal law and a decades-old legal settlement prevents the government from detaining families for longer than a few weeks.

“As a country, I don’t know that we can sustain more of this,” Ortiz said. Overall apprehensions at the border dropped to a historic low last year before rising again slightly in 2018, but the number of families coming here has reached record highs. More than 25,170 crossed in November — 23,012 in the Rio Grande Valley.

Nowhere else to go

The agency is working on a proposal to Congress that would allow civilian employees, rather than trained Border Patrol agents, to process families, a change that Ortiz said would be a “huge boost.” But he still maintained a fence is important enough to warrant a possible government shutdown.

“We don’t need a wall from sea to shining sea. There are areas where that doesn’t make a lot of sense,” he said. “But I recognize we have an opportunity to make a difference here in South Texas and I hope that happens.”

Fifty miles north in Roma, Assistant City Manager Freddy Guerra called a fence “absurd.” As mayor several years ago, he oversaw an evaluation of Starr County that found its terrain was “not conducive” to fencing. The dozen or so miles slated would slash through houses, which on this stretch of the Rio Grande hug its hilly sandstone bluffs. The estimated cost for building the structure in the county is $196 million, which Guerra said is equal to the entire appraised value of Roma.

“They can literally buy us out,” he said.

City officials are concerned about where displaced residents would go and whether the fence would impede the flow of water to the river, aggravating flooding. Guerra said the government after the Secure Fence Act of 2006 notoriously offered prices much lower than market value. In Roma, where the median income is $21,000, many people don’t have elsewhere to go.

“I just hope they pay me something that is fair,” said 60-year-old Francisco Garza, whose mother brought this cliffside house decades ago after bringing the family over from neighboring Miguel Alemán. Officials have told Garza a fence would go on the street line directly in front of his tiny property, for which a man recently offered him $300.

A few blocks south, Anita Loera strolled down to the riverbank abutting her backyard. Several Border Patrol boats whizzed by, and a denim jacket had been discarded in the mud overnight.

“We’re used to them,” she said of migrants crossing past her house. “ Pobrecitos. They just pass by running.”

She is also used to the ever-present Border Patrol agents, who she said usually wait outside her house in two or three trucks overnight. City officials say about 1,000 law enforcement officials — including Border Patrol, National Guard, sheriff’s deputies and police — patrol this county of roughly 60,000 people.

“I don’t even notice them anymore,” Loera laughed.

A powerful light blazed on from a towering pole across her house where acamera appeared to have noticed Loera’s movements on the bank.

“They just put that up last month,” she said. “Let’s go, they’re probably going to come.”

‘That would be a shame’

Back in Mission, Phyllis Schneider had come to visit the historic La Lomita Chapel, which is separated from Cavazos’ property by an RV park for retirees. A proposed extension of the border fence would cut off this beloved adobe building, first built in 1865. The government has filed a Declaration of Taking to use eminent domain to seize the Diocese of Brownsville property.

“Why can’t they put the wall someplace else?” asked Schneider, 69, who is from Wisconsin but is spending the winter here. “How would people come to visit?”

To her husband, Brian, it was a necessary, albeit regretful, reality.

“Either you protect yourself or you let them come over here and take over,” the 72-year-old said. “As far as I’m concerned, they can’t build the wall fast enough.”

Schneider wasn’t so sure.

“It has fresh flowers in there. It means something to somebody,” she said of the chapel. “There’s not a lot of historical structures left in this world. If there was a wall back there, that would be a shame.”

Cavazos’ cousin, Anzaldua, walked down to the river abutting his family’s property, gazing out 200 yards across the water to the same tin roof where Border Patrol agents had earlier spotted a smuggler’s scout. Anzaldua said he and his cousin grew up on this land, picking oranges and cotton and learning how to hunt and fish.

“Why do you need a wall here if you have such awide river?” he sighed.

He said Border Patrol agents recently stopped Cavazos’ sister when she walked over the levee and into her property. When she told them her family owned the land, they asked her to show them her deed.

“How would you like it if someone told you when you could enter or exit your house?” Anzaldua said.

Then he began walking back up the muddy dirt road to the levee, just as Father Roy Snipes drove down to the bank. Snipes, the pastor of neighboring La Lomita chapel, rents space from the Cavazos family for a church camp. He said he had just spoken to Georgetown University lawyers who said they could perhaps help their fight.

“I hope they can stop the wall,” said Snipes, his white truck emblazoned with a sticker saying “No wall between amigos.”

“I hope so too,” Anzaldua said.

On the levee, he waved to aBorder Patrol agent parked nearby, then climbed in the van to go home. lomi.kriel@chron.com twitter.com/lomikriel