Preserving memories of Pearl Harbor

Woodlands woman aims to teach as survivors dwindle

By Marialuisa Rincon STAFF WRITER

The still Hawaiian morning began like any other.

Ann Summers McKennis’ parents had been out late into the night and were still in their pajamas when the first wave of Japanese bombers roared over the Hickam Air Force Base’s officers quarters on Dec. 7, 1941.

Her father, Army Air Force First Lt. Thomas B. Summers, dressed as he ran out of the bedroom, through the family’s kitchen and into World War II.

Only 15 months old at the time, McKennis remembers little of that day, save for the deafening and interminable booms that followed the military base’s evacuees as they fled into the mountains. The bombers were so low, her mother later told her, she could see the expressions on the pilots’ faces.

“After that, every time a plane went over, I’d go hide under the bed,” said McKennis, now 78.

As a child survivor of the attack on Pearl Harbor, The Woodlands woman is a member of a club with a heavy cross to bear.

The Houston-based Bluebonnet Chapter 3 of the Sons and Daughters of Pearl Harbor Survivors — an offshoot of the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association — is carrying its work into another generation. But it becomes more difficult as the clock ticks further away from the attack 77 years ago, with just five direct survivors in the Bluebonnet chapter nearing their mid-90s.

“In each succeeding generation, there’s fewer people involved,” said Rick Lawrence of League City, who leads the Bluebonnet chapter.

‘Keep them curious’

For two days, McKennis, her mother and hundreds of evacuees waited quietly in the mountains for orders, fearing for their lives should the Japanese make their way inland.

The toddler and her mother were on the first transport ship back to the mainland and spent the war with extended family in Michigan. Most of McKennis’ knowledge of the attack comes from them — save for one brief trip home, her father spent the entire war in the Pacific Theater.

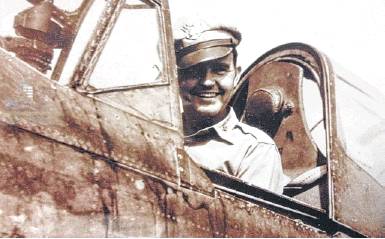

Thomas Summers was a dashing man with blue eyes and a kind face, adored by his family and the center of his daughter’s world.

But even when he came home after the end of World War II, he was reluctant to share with his family what he saw in the four years they were apart.

“He was a good man and a great dad,” she said. “But men didn’t really talk about what they saw in the war. You get busy with life and with family and children and jobs — you just don't take the time to ask. I do regret that.”

Life continued after her father came home. The family made port in Japan on Ann’s sixth birthday to aid in the post-war rebuilding effort, then lived briefly in Washington, D.C., before being sent to China. The world was changing by the time the family came home to Alabama in the mid-1950s.

It was the beginning of the civil rights movement in the state, she said, but her life after Pearl Harbor — the years spent living as a guest in countries so different from her own — shaped her world-view into a diverse acceptance of every person as an equal.

“A child's mind doesn't work that way,” McKennis said. “I was raised where I never knew any hatred or prejudice.”

In Alabama, she finished high school and attended nursing school in Michigan, where she met Jeffrey McKennis, who became her husband. Her father eventually retired from the military as a colonel in the late 1960s after also serving in Korea, Vietnam and Taiwan.

She moved to The Woodlands in 1984 when her husband accepted a job with a large oil and gas company. Her parents died soon after — her mother in 1985 and her father in 1990 — but she says she works to carry on their legacy of acceptance and respect every day.

Keeping memories alive

While preparing to attend the 75th anniversary of the attacks in 2016, McKennis joined the Sons and Daughters of Pearl Harbor Survivors. The organization, she said, is crucial in perpetuating the memory of such a crucial event in American history.

“Hopefully, we can reach young people and keep them curious about the attack,” McKennis said.

The group is an offshoot of the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association, which was formed in 1958 by 11 U.S. Armed Forces veterans who were stationed in Hawaii that day.

In 1972, facing dwindling membership as survivors and veterans began to age, the PHSA established the Sons and Daughters of Pearl Harbor Survivors. In 2016, with its members too few and too frail to travel, the PHSA officially disbanded and ceded its efforts to continuing education to the Sons and Daughters organization.

The Bluebonnet Chapter 3 is among the most active in the country, encompassing dozens of members from Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas and Louisiana, Lawrence said.

The chapter regularly makes presentations at the Brazos Valley Veteran’s Memorial, Wings Over Houston and several schools in the area to educate the community on the attack, its cause and how it led into the war.

Membership in the organization is open not only to the children of veterans and child survivors but to anyone interested in educating children and adults about the attack that launched the nation into World War II.

McKennis continues to carry on the mission.

“Never forget history,” McKennis said. “That’s how this country was made. Good, bad, or indifferent — it's our history.” mrincon@chron.com