TRANSPORTATION

Beyond diesel, a race to fuel the bus of the future

Local, state governments across country working to overhaul fleets, but transitions challenged by limits to infrastructure

By Gerald Porter Jr. BLOOMBERG NEWS

There’s no denying it: Oil, once the lifeblood of America’s buses and trucks, is no longer king of the fleets. Two decades ago, diesel and gasoline fueled virtually all of the country’s municipal buses. Now, they burn in less than 45 percent.

A smorgasbord of natural gas, diesel-battery hybrids, biodiesel and electric vehicles worked together to end oil’s reign. Today, they’re all jockeying for the chance to fuel the fleet ofthe future.

While bus and truck pools account for just a fraction of the vehicles on America’s roads, they’re responsible for generating 80 percent of the smog and as much as a quarter of the nation’s transportation emissions. That has local and state governments across the country working to overhaul their fleets, touching off a race to gain an early edge and dominate an industry that consumes 1 billion gallons of fuel a year and spends $5 billion annually on buses alone.

“New technologies are coming out more quickly than we can even wrap our head around,” said Erik Johanson, director of innovation at Philadelphia’s main transit authority. “What we’re creating is a new system.”

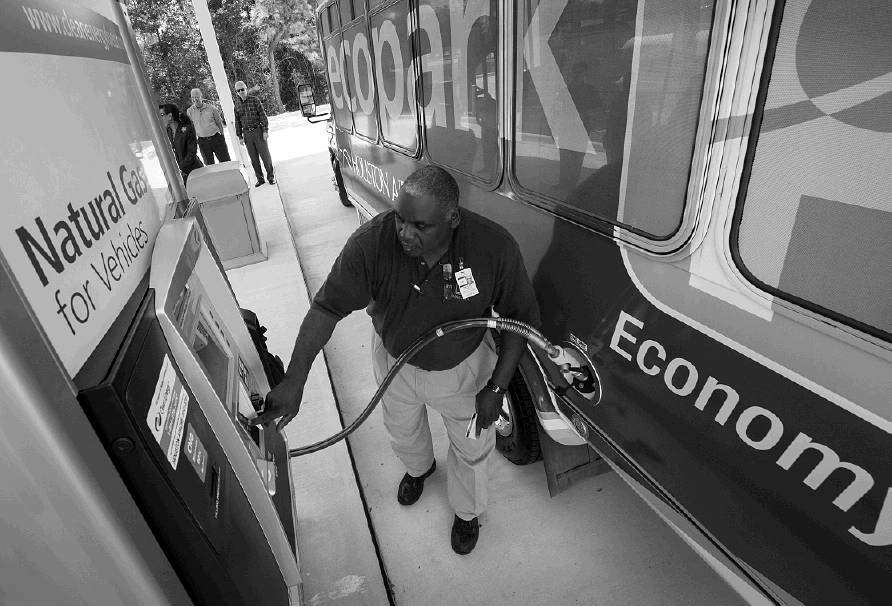

Natural gas is largely to thank for oil’s decline across U.S. fleets. It fuels 29 percent of the nation’s buses now, up from less than 19 percent a decade ago. And it has economics on its side: The price of cleaner, gas-fired buses has reached parity with diesel ones — and can be even cheaper with federal grants.

The fuel itself is also less expensive, said Floun’say Caver, the interim chief executive officer of the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority. Since 2015, the Cleveland agency has spent nearly $70 million on 133 compressed natural gas — or CNG — buses, which now make up about 40 percent of its fleet. It’s a worthwhile price considering the authority pays about $1.35 a gallon less at the pump compared with diesel, Caver said. He estimated $75,000 in savings over the 12-year life of a typical bus.

Gas meanwhile emits 22 percent less greenhouse gases than diesel and 29 percent less than gasoline, according to a report for the California Energy Commission.

The same fleet operators, however, are still trying to figure out how to pay for the gas pipelines and filling stations needed to keep CNG vehicles on the road. In Atlanta, one new CNG station cost almost $16 million. At that point, “the bus is the least of your worries,” said Tom Young, assistant general manager at the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority.

One make-or-break moment for CNG, he said, will be whether the U.S. extends an alternative fuel tax credit. It has been passed by a House committee but may face objections in the Republican-controlled Senate. If extended, investing in CNG is a “no-brainer,” Caver said.

While electricity drives only about 0.1 percent of bus fleets today, some transit agencies already have their eyes set on emissions-free power as the fuel of the future. Johanson, at Philadelphia’s main transit authority, calls EVs the “game-changer” in the transition from diesel. Filling up on power costs about $1.30 per gallon-equivalent, making it the cheapest among competing fuels.

Proterra Inc. has already seen 25 of its battery-powered buses hit Philadelphia roads last month. Another 10 from NFI Group Inc.’s New Flyer are scheduled to arrive in 2021. These first deliveries are a litmus test of sorts for battery-powered buses.

Just like CNG, electric buses face an infrastructure challenge. A lot of people “think this is just plugging a bus into the wall,” but it’s more complicated, Johanson said.

From needing “a massive amount of power” to paying for the costs of charging stations on top of the buses themselves, agencies are buying into a “complete system” when they go electric, said David Warren, director of sustainable transportation at NFI.

“Infrastructure is absolutely a huge investment,” he said. “It’s much more than the bus.”

The e-buses available today also haven’t been thoroughly proven to handle the mileage and wear that’s demanded of a city bus, said Young, from Atlanta’s transit authority.

This may actually be the biggest bull case for CNG buses, which could serve as a gradual bridge from diesel to electric — a transit agency’s way of biding its time until battery costs come down more, Warren said.