MISSION MOON: HC SPECIAL SERIES

WHAT COMES NEXT IN SPACE EXPLORATION?

Big ideas need big money to get NASA off the ground

By Alex Stuckey STAFF WRITER

The NASA of today still has big dreams for space exploration.

A space station orbiting the moon. A base on the lunar surface. A human mission to Mars. A telescope to unveil the origins of the universe.

They’re some of the same dreams held by scientists 50 years ago, when the U.S. captivated the world by putting men on the moon.

But even then — when space exploration was new and exciting, when money flowed to the fledgling space agency to prove America’s superiority in the world —the dreams fell short of reality.

It’s an even tougher sell now.

Instead of being flush with money, NASA is struggling to pay for projects, with some continually falling behind schedule. Instead of unwavering support from the American public, NASA is fighting to stay relevant, with many arguing that space is not worth the money.

And instead of continuing to explore deep space, NASA has spent decades in low Earth orbit.

“It’s not a race anymore,” NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine told the Houston Chronicle. “The 1960s are over. It’s about international collaboration; it’s about American leadership.”

It is time, many experts say, to travel beyond the Earth’s gravitational pull. But without a space race to win, without Cold War tensions, it will be difficult to get the political and monetary backing needed to go anywhere fast.

“The thing about Apollo is that because it was essentially a wartime effort, a lot of corners were cut … a lot of resources were poured into it,” said Pascal Lee, co-founder and chairman of the Mars Institute, a nonprofit headquartered at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California.

“With that level of support, we would be able to pull it off,” he said. “But we can’t do it with the current funding level.”

‘A masterpiece of simplicity’

The future of space travel looked bright for scientists when the U.S. beat the Soviet Union to the lunar surface on July 20, 1969 — a feat accomplished just eight years after President John F. Kennedy vowed to put a man on the moon.

They envisioned a world where igloolike domes dotted the rocky lunar surface, home to people living and working in outer space. They pictured their country embracing a Mars mission, touching down on the dusty, red surface less than 15 years after Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon.

They thought humans would never stop exploring space, traveling deeper and deeper into the cosmos.

But the Apollo era was a special time, when political will and funding aligned in unison. Those days petered out, as did society’s interest in deep-space travel, and what happened over the ensuing 50 years was much less glamorous.

Americans have not touched the lunar surface since 1972, and plans to return have repeatedly been axed. A lunar civilization is not part of immediate plans, and Mars is an idea for dreamers that gets pushed back seemingly indefinitely.

When Gene Cernan took the last step on the moon’s surface in December 1972, President Richard Nixon already had announced the country’s next big space endeavor: the space shuttle.

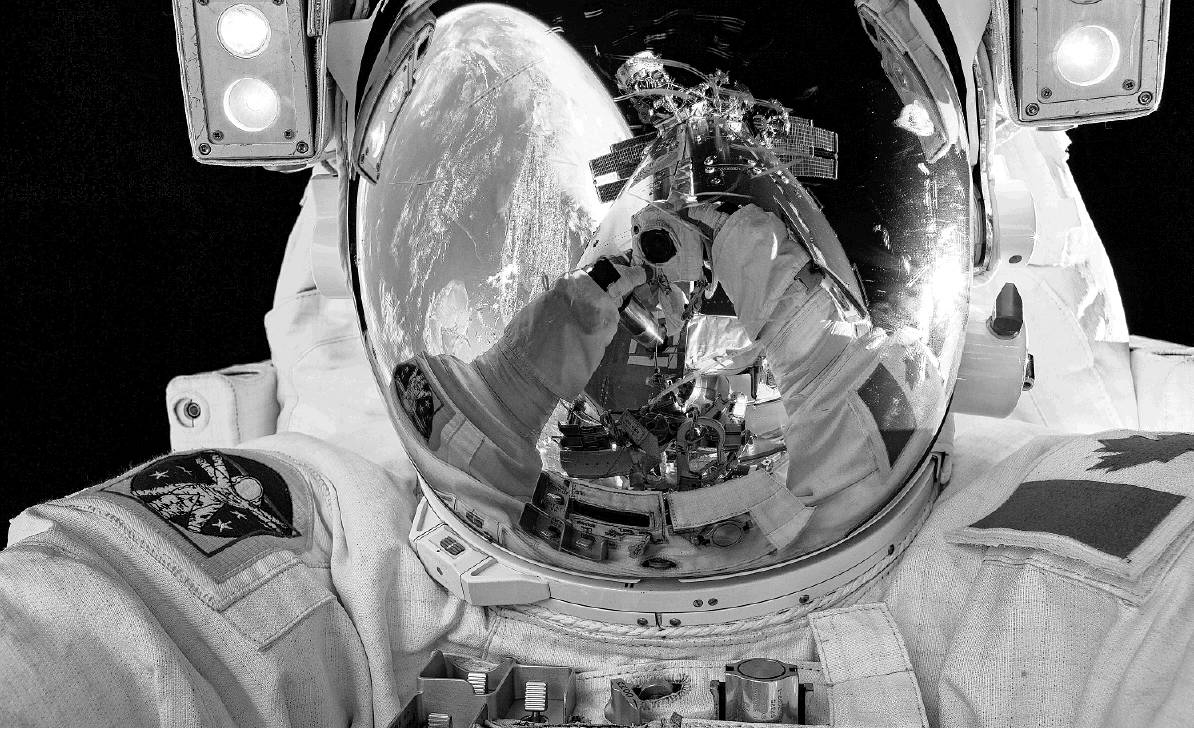

Instead of rocketing deeper into space, NASA would focus on an area closer to home: low Earth orbit. And since 1981, that’s where astronauts have been going, first for short-duration missions aboard the space shuttle and now for monthslong stints on the International Space Station.

Since the late 1980s, presidents have been trying to push astronauts farther into space by evoking the sense of purpose and inspiration in Kennedy’s moonshot speech.

Kennedy’s goal to put humans on the moon before 1970 “was a masterpiece of simplicity,” Apollo 11 astronaut Michael Collins said in April at the National Press Club. “That masterpiece of a statement gave us our marching orders. It told us what to do and when to do it. And it was the how-to-do-it that was up to us.”

But so far, each has failed.

“It’s going to be hard without a real message and a real reason and areal justification,” said David Alexander, director of Rice University’s Rice Space Institute.

Beating the Russians

The imperative to beat the Soviet Union to the moon in the 1960s wasn’t really talked about, but Apollo 7 astronaut Walt Cunningham said everyone working on the project knew it was crucial.

If America didn’t make it there first, the country could lose its superpower status. It could fall behind technologically and militarily — it could be looking at a world in which a communist country militarized space.

The competition inspired the U.S. to throw its weight behind the mission and Congress to open its purse strings.

“Back in those days, we were oriented toward beating the Russians …and we really beat the Russians,” Cunningham said. “We did that because people were oriented along those lines.”

But now, 50 years later, there’s no space race to win; there’s nothing to stir America’s competitive nature.

And without that competition, many experts question whether America can accomplish what it once did.

“This goes back to the history of exploring: Very little happens unless there’s a race,” Lee said. “People went to the North and South poles because there was a race. Even Chris Columbus got funded because it gave Spain a competitive edge. It was not for the cool factor, it was for the competition.”

With Russia now an ally in space, some have pointed to China as a potential competitor. Federal law even prevents the U.S. from working with the Chinese in space.

But when China landed a probe on the far side of the moon in January — a feat no other country has accomplished — NASA sent out words of congratulations instead of declarations of battle.

“This is a first for humanity and an impressive accomplishment!” Bridenstine tweeted shortly after the landing was confirmed earlier this year. He has since said he would not be against working with China if the law changed.

Since being sworn in as NASA administrator in 2018, Bridenstine has touted the importance of working with international and commercial partners in space. The additional brain power and, of course, money can only help America reach for the stars, he has said.

And he has signed plenty of agreements with other countries, including the United Arab Emirates, Japan, Canada, Greece and those that make up the European Space Agency. NASA also is working with Israel on its next attempted moon landing after the Beresheet probe crashed into the surface in April.

And Bridenstine promised to do even more as NASA rushes to follow a directive from President Donald Trump to return quickly to the moon.

“If anyone is suggesting to you that NASA is falling behind, know this: We are not,” Bridenstine said during a lecture at Rice University in April. “We are ahead, and we are continuing to move ahead, but here’s what’s new: This is not just about how great NASA is. We’re doing it with our international partners.”

Delays and more delays

NASA still has accomplished big things in recent years: Scientists sent a probe to the sun; landed their eighth successful mission on Mars; and zoomed past Ultima Thule, a celestial object 4 million miles away.

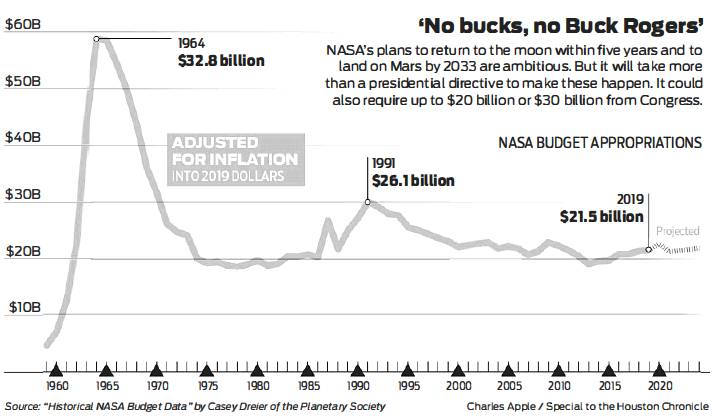

But a roughly $21 billion per year budget — about the same as what the whole Apollo program received, not taking into account inflation — can allow for only so much progress.

And many NASA projects have fallen behind:

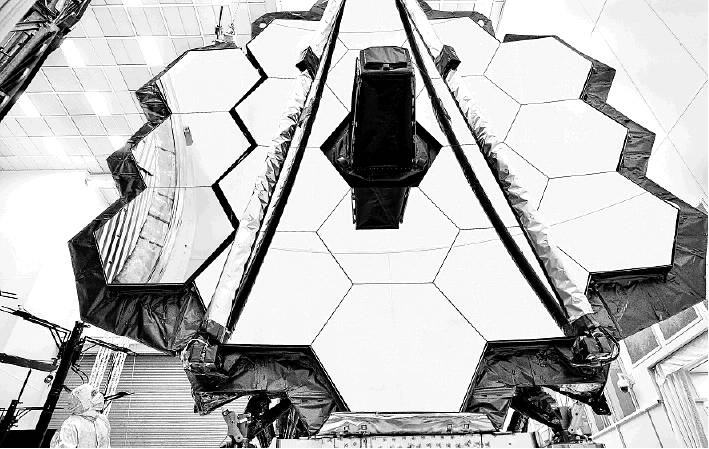

• The James Webb Space Telescope, the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope, is supposed to reveal the origins of the universe, but it’s more than a decade behind schedule and is projected to cost $9 billion more than the less than $1 billion originally estimated. Initially set to launch in 2007, James Webb is now delayed until 2021 at a cost of $9.7 billion.

• Hubble, meanwhile, is limping along after three decades in Earth’s orbit. Astronomers are worried it could fail before the Webb telescope is launched, leaving them without a groundbreaking telescope to study the stars.

•The Space Launch System rocket, the largest rocket the U.S. has ever built, has faced major problems as well. NASA plans to use the rocket to get humans back to the moon, but Boeing recently told the space agency it would not be ready until 2021, a year after NASA had planned to launch it to test the Orion spacecraft. The SLS rocket, which was supposed to launch in 2017, has cost NASA $13 billion so far.

•InSight — short for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations Geodesy and Heat Transport — finally landed on Mars in December to study the planet’s interior. But that happened after a delay of more than two years that increased the cost by $154 million, bringing the total cost to $850 million.

•NASA’s ICESat-2 — short for Ice, Cloud and Land Elevation Satellite-2 — faced delays before it launched in September to collect data on Earth’s ice sheets, tracking changes in glaciers and sea ice. The delays cost taxpayers an additional $140 million, bringing the total cost to $1 billion.

As the agency struggles for adequate monetary support for its growing list of projects, many have turned their sights to private companies that promise to build similar products faster and more cheaply than the government.

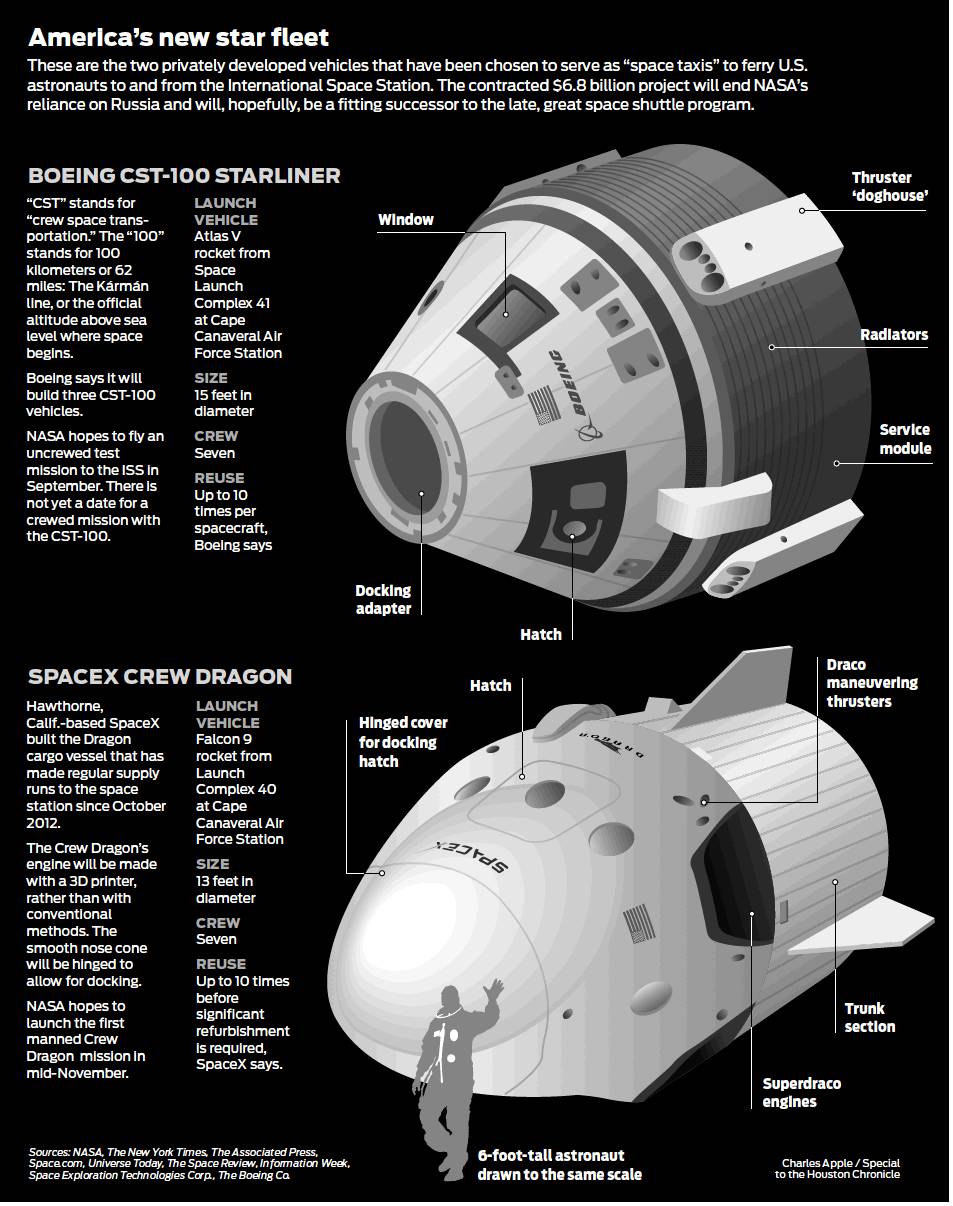

But success in that arena has been haphazard at best. After the space shuttle program was canceled in 2011, NASA turned to private companies for a cost-effective vehicle to transport its astronauts to and from the space station. Contracts totaling $6.8 billion were awarded to Boeing and SpaceX in 2014, but both companies have struggled to meet the standards for transporting humans laid out by NASA.

Neither company met the deadline to launch in 2018. Boeing still has not conducted its test flight without humans aboard, and though SpaceX successfully completed that test in March, the company suffered a major setback in April when the capsule suffered an “anomaly” during engine testing.

Meanwhile, NASA continues to pay for seats — at $82 million each — on the Russian Soyuz spacecraft so the U.S. can maintain a presence on the space station. And the American space agency likely will need to rely on international and commercial partners if funding levels do not improve.

Politics and money

The future for NASA comes down to money. And that means, in the end, it comes down to politics.

If there is not enough political will to explore the cosmos, the money will not come. And if money doesn’t come, it won’t be possible to explore.

Experts say it’s unlikely that NASA will receive 5 percent of the federal budget again, as it did during the Apollo era. But it’s heartening to many that Trump has put a focus on space exploration since taking office in 2017.

Trump’s support of NASA brought a $1 billion increase in the agency’s budget in the current fiscal year, but whether his elaborate plans to return humans to the moon by 2024 come with the necessary funding is still to be determined.

“If the president says do something, then we make sure we have the resources to do it,” Apollo 15 astronaut Al Worden said. “That’s what Kennedy did. And we haven’t had a president do that since.”

But even if the Trump administration funds the projects, will future presidents carry on that vision?

If history is any indication, they won’t. NASA has struggled for decades to make programs stretch beyond presidential terms. The plan for the Orion spacecraft, for example, has flip-flopped between the moon and Mars since the early 2000s.

Alexander thinks there are several ways to fix the problems. For one, Congress could make the NASA administration position a 10-year term, like the FBI director, to help exploration visions carry over between presidents.

Congress also could provide multiyear appropriations to the agency, which would allow some security when planning massive projects, such as the moonby-2024 plan.

But Alexander knows this would be a tough sell for congressional leaders.

“Nothing takes two years, and that means you’re giving up, as a congressperson, you’re giving up some power,” Alexander said. “But if you don’t do that, unless you just happen to have someone come in that’s good with the previous guy’s idea, I think the programs will suffer.” alex.stuckey@chron.com