BUSINESS

Yeah, but is she ‘likable’?

It shouldn’t matter whether women smile so long as the job gets done

By Jennifer Latson

In one of the most stunning twists of the final season of “Game of Thrones ,” teenage ninja zombie-killer Arya Stark achieved what no other warrior could: She took out the Night King. And as she ascended to her rightful place at the top of the Westeros hero hierarchy, the obvious question soon emerged.

“Ah, but is Arya likable enough?” tweeted Vox.com co-founder Matthew Yglesias.

It’s a question that seems to have plagued powerful women from the World of Ice and Fire to the 2020 election landscape. Whether you can get the job done is a secondary concern; people first want to know you’d be fun to grab a beer with. Responding to Yglesias’s tongue-in-cheek tweet, commenters joked that Arya should try smiling more.

The phenomenon is no joke, though. Women in so-called masculine occupations (such as politician or assassin, along with pretty much anything in the STEM world) tend to be seen as either competent or likable, but rarely both, according to a 2004 study led by NYU organizational psychologist Madeline Heilman. When women succeed in these areas, they are more often disliked and denigrated —labeled cold, selfish, deceitful and devious, along with more colorful descriptors — than similarly successful men, Heilman found. And this isn’t just personally hurtful: Being perceived as unlikable can have career-altering consequences.

“These characterizations provide some insight into why, despite their success, high-powered women often tend not to advance to the very top levels of organizations,” Heilman writes. “As with Ann Hopkins, whose denial of partner status at Price Waterhouse was eventually reviewed by the U.S. Supreme Court, women may well be applauded as competent and accomplished but may also be seen as personally abhorrent.”

When did we become fixated on the idea that our top bosses and officials needed to be likable? After all, it’s just one of many traits we value in a leader, while others, like competence and creativity, seem like they should rank higher. Interestingly, however, both of these traits tend to work against likability, according to research by Rice Business management professor Jing Zhou.

In a 2017 study, Zhou and her colleagues found that an organization’s most competent workers tended to be disliked by their peers, who often actively sought to undermine them. “Their teammates were ambivalent toward high performers,” she explains. “We’re kind of torn between the tension of wanting our teammates to be competent when we’re working with them, but when we’re competing for a promotion, that becomes a liability. And there’s a natural emotional response to perceiving someone as better than you. Lots of people feel like, ‘Well, that means I’m not as good.’ You take it personally.”

The same goes for an organization’s most creative members, who tend to evoke dislike by challenging the status quo, Zhou says. “They’re asking questions and proposing new ways of doing something, and those tend to make people uncomfortable,” she explains. “Psychologists find that when we’re uncomfortable, we try to find atarget to ascribe those feelings to. So it’s not ‘I’m uncomfortable thinking along these lines’— it’s ‘She makes me uncomfortable.’”

Clearly, it would be bad business to devalue your most competent and creative employees, whether or not you like them. But studies show that managers routinely do.

Likability wasn’t always essential to climbing the corporate ladder. In fact, its career-shaping power is a relatively recent phenomenon, according to Claire Bond Potter, a history professor at the New School.

“Likability seems to have emerged as an important personality trait in the late 19th century, when it became closely associated with male business success,” Potter wrote in a New York Times op-ed last month. “Before this, people liked or disliked one another, of course, but it wasn’t until after the Civil War, when middle-class men began to see virtue and character as essential to personal advancement, that success in business required projecting likability.”

Today, given how important likability is to clinching a candidacy or a promotion, many of us are eager to learn how to attain it. Luckily, Washington Post columnist Alexandra Petri recently outlined a few simple steps.

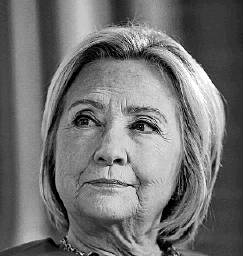

“It must be clear that you can hang. You must be able to take jokes. Your laugh must be a good laugh, not a cackle or a guffaw or a hoot,” she writes. “You must be effortlessly natural but also meticulously and faultlessly prepared. You must be warm, but not too warm — like a cardigan, never a pantsuit. You must be well-informed, of course, but not tiresome. No haranguing! If possible, do not remind people of their mothers, or Hillary Clinton, whichever comes to mind first.”

It's true that likability also plays a part in whether men are hired, promoted or elected. But men can cackle or guffaw or hoot — or not smile very much at all — and still be liked. And their likability doesn’t decline as their careers advance.

“Success and likability are positively correlated for men and negatively for women,” Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg writes in Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead. “When a man is successful, he is liked by both men and women. When a woman is successful, people of both genders like her less.”

Every so often, a new study claims to overturn decades of sociological research and demonstrate that women can be successful and likable. But these studies are invariably flawed. Take the 2013 study by leadership development consultants Jack Zenger and Joseph Folkman, who concluded that women actually maintain their popularity as they rise through the ranks. Women everywhere would have rejoiced if their findings had been correct — but they weren’t, writes Marianne Cooper, a sociologist at Stanford University and the lead researcher for Sandberg’s book.

“If likability and success are negatively correlated for women, how then did Zenger and Folkman arrive at their conclusion? Setting other methodological concerns aside, it’s because they are not measuring likability,” Cooper writes. “Instead, their ‘index of likability’ seems to measure interpersonal skills, which is an aspect of leadership ability, but not likability.”

The inherent unfairness of likability is that it takes a subjective, external circumstance — whether or not you like someone — and ascribes it to that person as an objective, internal trait: whether they warrant liking. In the kinds of scenarios where likability is often a make-or-break factor, like hiring a manager or electing a president, the irony is that whether you like them has little bearing on how well they’d do the job.

“What would it mean if we could reinvent what it is that makes a candidate ‘likable’?” Potter asks. “What if women no longer tried to fit a standard that was never meant for them and instead, we focused on redefining what likability might look like: not someone you want to get a beer with, but, say, someone you can trust to do the work?”

Arya Stark proved that she could be trusted to get the job done — but if she’d spent more time smiling and less time sword fighting, who knows whether she could have ever pulled it off. For now, successful women still have to do both: Smile sweetly and carry a sharp sword.

Latson is the author of “The Boy Who Loved Too Much” and a senior editor at Rice Business.