CLIMATE CHANGE

Mars can wait. First, let’s terraform Earth.

By Blake Hudson

I love living in Houston, the Space City. I take my sons to NASA’s Johnson Space Center frequently, hoping to inspire interest in the universe. Recently we returned from Family Space Camp at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Ala.. They were excited about NASA’s plans to return to the moon and travel to Mars within the next few decades.

Being in environmental law, I have hoped that my children would pursue a profession that brings happiness and hope, rather than frustration and anxiety over the state of the world. Space and the sciences critical to space exploration can do that.

But I am of two minds when it comes to space travel these days. By pushing toward new frontiers, investing in NASA has resulted in some of the most important technological advances in our society. I have always considered the cost worth it, even if we fail at times. Ultimately the human race should look to expand beyond the confines of this planet. But we will be unable to do so if we do not take care of this planet first.

Every day it becomes clearer that Earth faces an existential crisis driven by climate change. We just crossed over the 415 ppm threshold for heat trapping atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations for the first time in human history — indeed, for the first time in at least 2 million years. And we show no sign of slowing down.

Last month a heat wave hit the southeastern U.S., shattering temperature records (102 degrees in Beaufort, S.C., for example). Heat-related deaths will increase dramatically by 2050, as will flooding, droughts and storm strength. We just witnessed the wettest 12 months ever in the U.S., and much of the Midwest is currently underwater, having significant impacts on agricultural production.

For every 1 degree Fahrenheit rise in temperature, the atmosphere holds 4 percent more water, and heavy precipitation events have increased dramatically in the last few decades. A recent event in my Kingwood neighborhood flooded 400 homes that did not even flood during Hurricane Harvey. The extra moisture in the atmosphere is no longer in the soil, resulting in drier landscapes that contribute to record-setting wildfires, such as those devastating California last summer.

Sea levels are rising faster than scientists have projected, threatening to inundate coastal cities by the end of the century. U.S. military and intelligence officials are increasingly concerned about refugees fleeing areas inundated by sea level rise or that become too hot for human habitation. And a recent major global insurance company predicted that insurance could become too expensive for most people unless drastic action is taken now. The free market knows what is happening, and the free market doesn’t lie.

If we are worried that changing course will hurt the economy today, it is pennies compared to the projected future economic impacts of climate change.

To avoid the calamitous effects of a 2 degrees or 3 degrees Celsius rise in global temperatures, we must not only reduce carbon dioxide emissions to zero in the coming decades, but also draw back out of the atmosphere the excess concentration of carbon dioxide put there since preindustrial times.

The technological capacity exists to do both, as I and other environmental scholars recently communicated in our book, “Legal Pathways to Deep Decarbonization in the United States.” But we must improve upon and scale up these technologies, and quickly, which will require harnessing all available resources.

NASA has been indispensable for gathering data and information about the state of the planet’s climate. But what if we diverted more of NASA’s budget — $21.5 billion in 2019 — to combat climate change?

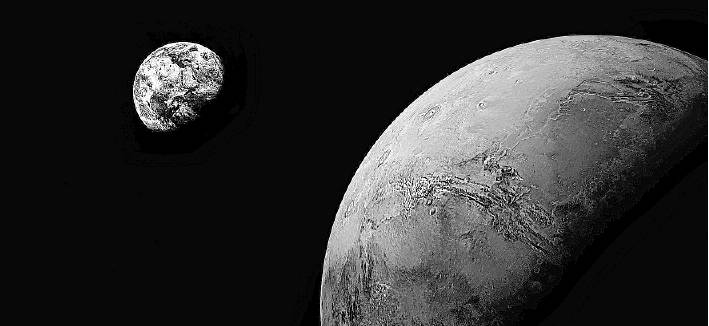

While NASA and Elon Musk may disagree about the viability of terraforming Mars — that is, making it capable of supporting human life — we need to first ensure that this planet is habitable, and that the stability of human society is not drastically interrupted.

Let’s invest NASA’s economic resources and expertise in climate solutions, and focus the brightest minds in Houston, Huntsville, and elsewhere on developing technologies to make this planet livable in the distant future. Only then will we have the luxury of supporting space flight in the next century.

We need to terraform Earth, ensuring that its atmospheric greenhouse gas levels are within the range that has allowed humankind to flourish (below 300 ppm). I share the dreams of NASA when I look up into the night sky. But let’s work to save this planet first, and then go to Mars.

Hudson is a professor of law and holds the A.L. O’Quinn Chair in Environmental Studies at the University of Houston Law Center.