Stage set for high-stakes water war

Conservation debate pits cities and utilities against river authority and board

By Emily Foxhall STAFF WRITER

CONROE — When San Jacinto River Authority officials began to treat water in Lake Conroe four years ago, sending it out to utilities and into Montgomery County homes, they filled Champagne flutes with the product and celebrated.

The region had previously relied on water from its underground aquifers, and some had worried they were pumping too much. But with a new, $480 million dollar treatment plant, they felt they had a sustainable system using both.

But someone had to pay for that plant. Water bills went up, people got angry and, in a political takeover befitting the conservative county, a new group backed by a local utility company and political action committees pushed aside those in charge last fall. They spent more than $100,000 in an election for an obscure regulatory board.

Now, a high-stakes water war is playing out in this suburb, where population growth is increasing water demand. A change in state law had primed the takeover. Lawsuits threaten the old system. Rules limiting how much could be pumped are being tossed, and concern is rising about whether the bonds that financed the new treatment plant will be repaid.

“Uncertainty is where we are right now,” said Jace Houston, general manager of the river authority, which issued the bonds. “We are doing contingency planning because we don’t know where this is going.”

Growing pains

Growing areas across the state are wrestling with how to meet water demands responsibly. Regulators must balance immediate concerns — keeping water affordable, limiting government meddling and encouraging economic development — against longterm environmental factors.

Removing too much water from aquifers can make water more difficult and costly to access. It can also cause land to sink, potentially worsening flooding. This process, known as subsidence, famously caused a 400-home Bay-town subdivision to sink in the 1970s and ‘80s.

Montgomery County was moving toward a system to stabilize its supply and, officials thought, avoid such problems. But the group that ousted the leaders making the decisions won out with a well-funded campaign focused on the now, promising reasonable bills and reform.

In March, the new officials managing the aquifers approved a plan to adopt different rules aiming “not to unnecessarily and adversely limit production.” The Texas Water Development Board must decide by Friday whether that plan is acceptable.

The group in charge has solicited community feedback and found support. People such as 55-year-old financial adviser Barry Tate are behind them. Tate’s water bill in March totaled $114.24, including $31.68 in fees for the water plant he didn’t think was needed.

“It seems to me like there’s a lot of over-regulation that’s occurred,” Tate said at a town hall meeting in Magnolia, drawing applause, “and as a result, we’re all, as taxpayers, paying a heck of a lot more for water than what we really should be.”

The group at the center of this battle is the Lone Star Groundwater Conservation District. Texas considers underground water private property but gives such districts power to manage it in specific ways. Today, 100 such districts cover around 70 percent of the state.

‘A balancing act’

Their task is “a balancing act,” said Larry French, director of groundwater resources for the state water development board. Each district is supposed to consider local needs while ensuring “conservation, preservation, protection, recharging, and prevention of waste of groundwater,” as the water code states.

State legislators created Lone Star in 2001, and voters confirmed it. Nine board members were appointed by different groups, such as the county commissioners court and the river authority. Their charge was three aquifers — part of the Gulf Coast Aquifer system — layered diagonally under a swath of the state like a tilted cake.

Some districts allow users to take more water from aquifers than is naturally replenished. (Utilities prefer to use groundwater because it is easier and cheaper to treat.) But Lone Star board members, concerned for the future, wanted to maintain their supply.

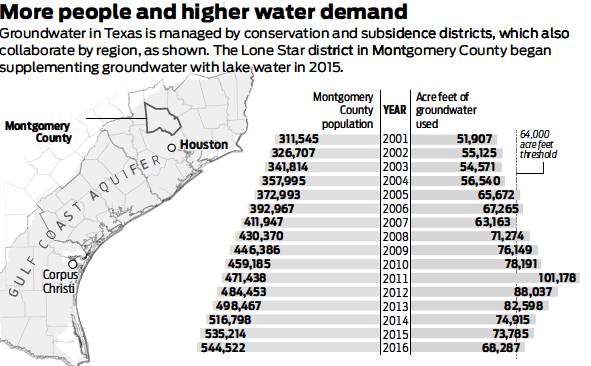

Lone Star determined that 64,000 acre-feet could be pumped each year and would be replaced. More than that was being used in 2005, and demand was only expected to increase. So the board members set deadlines.

They intended groundwater use to be limited to 64,000 acre-feet per year by 2015. They required large water users to figure out how to substitute 30 percent of what they took from aquifers with another source.

“We were trying to be ahead of a problem,” said Kathy Turner Jones, the former general manager of the district. But new problems arose.

Growth and worry

The San Jacinto River Authority, a governmental entity, holds the rights to Lake Conroe’s water, the most obvious alternative to groundwater. The lake was completed in 1973 to serve that purpose.

Houston, the authority’s general manager, was glad to see the district tackling these issues. In a previous job at the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District, he saw the costly consequences of aquifer overuse.

“We’re not playing around,” Houston said. “This isn’t make-believe.”

Harris and Galveston officials had drastically cut groundwater use in two regions, and the ground nearly stopped sinking. They turned to lakes Houston and Livingston to help make up the difference.

When the river authority moved toward asimilar approach in Montgomery County, the utilities went along. Around 80 signed contracts with the river authority, promising to pay off the cost of building the Lake Conroe treatment plant.

Some would later argue the utilities had no choice, suggesting a conspiracy between Lone Star, which required the cuts in groundwater use, and the river authority, which offered the solution and had a member on Lone Star’s board.

The river authority adopted fees, issued bonds and started building.

Staff graphic

Political takeover

Lone Star issued final rules for reduction in 2015. The river authority finished the treatment plant. The stage for their water war was set.

The city of Conroe and seven private utility companies sued Lone Star, claiming the district lacked authority to do what it proposed.

Conroe stopped paying the river authority’s increasing fees, accusing the authority and district of promoting “a false narrative based on bad science.” The city of Magnolia stopped paying higher rates, too.

In 2017, two Conroe Republicans pushed a bill to passage requiring that the Lone Star board be filled by seven elected members instead of nine appointed ones.

State Rep. Will Metcalf, who authored it, and Sen. Brandon Creighton, who sponsored it, said residents and business owners were frustrated with high water bills and what they saw as a lack of accountability by an appointed board.

The election for new board members was set for 2018 — and one man in particular was determined to see that a new slate of candidates , with a new perspective, prevailed.

Simon Sequeira, the president of a Magnolia-based utility company called Quadvest, didn’t believe the plant was necessary yet. He wanted Lone Star’s rules invalidated, and his company was among those that sued the agency.

Sequeira formed a group called Restore Affordable Water, or RAW, which backed a slate of candidates with messaging around property rights and runaway politicians that resonated across local media.

“Let’s not fall for the story that the sky is falling and we’re going to run out of water,” Sequeira urged on the radio.

The RAW political action committee reported spending $97,571.50. Other PACs such as Freedom and Liberty Conservatives, Republican Voters of Texas and Texas Patriots State PAC supported the slate.

Ten barely-funded opponents faced them, including incumbent Rick Moffatt, a municipal utility district manager in the county.

Moffatt couldn’t believe what was happening. Lone Star policies had finally steadied the falling water levels that were critical to his work. He reported spending $910.38 of his own funds to try to stay on the board.

But it appeared he and his colleagues were being replaced.

Still churning

All six candidates on the RAW slate won. A seventh candidate was uncontested.

They were sworn in Nov. 16, 2018, hired new attorneys and settled the suit filed by Quadvest — the company that helped elect them — against the board they now represented.

Sequeira said he expected only that they do what was right.

The settlement invalidated the 30 percent pumping reduction. The board notified large water users that once the final paperwork is filed, the requirement “SHALL BE STRICKEN.”

A former mayor of Con-roe, Webb Melder, the only incumbent board member elected, now heads the board. Lone Star’s longtime general manager got a different job.

Hydrologists retained by the new group argue that there is plenty of water available in the aquifers. They say subsidence, which measures around two to three feet in parts of the county, is not a concern in other areas there.

An attorney for the board said board members and consultants were unavailable to comment for this story.

Officials in Montgomery County are paying attention to the looming decision by the water development board. Among them is James Stinson, a former Lone Star board member and now the general manager of The Woodlands Joint Powers Agency, which oversees water in the community.

Stinson wrote to the board to oppose the plan, arguing it would “undoubtedly result in additional pumping … above sustainable levels and increase the risk of additional water level declines, land subsidence and flooding.”

So are those in Harris County, which shares the same aquifers, and where local water authorities are cutting groundwater use in the remainder of the county, spending $380 million to channel water 26 miles from the Trinity River to Lake Houston.

Contract battle

Still, Lone Star interim general manager Samantha Reiter said at the town hall meeting that they had “no intention of ‘turning on the faucet.’ The district intends to follow the law and takes that duty very seriously.”

Today, the Lake Conroe treatment plant processes an average 12 million gallons of water a day. It has capacity for 18 million more, and planners left room for three more expansions.

In 2017, the American Water Works Association ranked Lake Conroe water the best-tasting in Texas. This year, it came in second.

Participating utilities pay the river authority $2.83 per 1,000 gallons of surface water delivered and $2.64 per 1,000 gallons of groundwater pumped. An average home uses 10,000 gallons.

Their fees go toward operating the plant and paying back the debt they took on to build it. The authority does not operate for profit.

Conroe and Magnolia still are not paying the higher rates. The river authority sued to force them to do so, and Quadvest, the utility company, countersued, claiming the contracts were “based on false premises, duress and mistake.” A battle over procedure in that case sits with the Texas Supreme Court.

Eventually, the river authority hopes the courts will reaffirm that its contracts are valid.

Conroe and Quadvest hope to get out of them. emily.foxhall@chron.com