Jasper awaiting closure, at last

Execution of Byrd killer set this week; town has worked to repair image

By Monique Batson STAFF WRITER

JASPER — James Byrd Jr. told his family that he would “put Jasper, Texas, on the map” one day, and he did.

“He thought it would be because of his music,” said Louvon Harris, one of his sisters, recalling the confident young man who played trumpet in the school band and sang exuberantly in the church choir or for anyone he thought it would bring joy to.

“Never did we think it would be because of his death.”

But it was Byrd’s murder — a horrific, white-on-black hate crime along a lonely country road — that brought notoriety to this East Texas town and created an impression that locals say was never quite true and has taken years to correct.

They hope Wednesday’s scheduled execution of killer John William King will be the final act in a searing legal and moral drama that has lasted nearly 21 years.

“Now when you mention Jasper, you associate Jasper with James,” Harris said. “It’s sad to know it was for a different reason than he anticipated.”

Byrd, a 49-year-old African-American known and liked around town, took a ride from King, a buddy of his from prison and another friend who worked at the local movie house. In an unconscionable rage in the early hours of June 7, 1998, the white men wound up chaining Byrd by his ankles to the bumper of a 1982 Ford pickup and dragging him for 3 miles before dumping his body on the side of the road.

The crime and the quick arrest of the killers —King a shocking figure with white supremacist tattoos — devastated the townspeople here as deeply as it did the rest of the nation. Yet from the beginning, their grief was overshadowed by the growing stereotype of their community as aplace where the whites were mostly racists and the blacks lived in constant fear.

The people of Jasper did their best to prove the outsiders wrong. They stayed indoors when the Ku Klux Klan marched through town. They did the same when the New Black Panthers Party marched through. Clergy members preached forgiveness and worked hard to keep lines of communication open.

They came together to address areas of legitimate concern, such as racial disparities in local hiring.

The Rev. Kenneth Lyons, the Byrd family’s minister at Greater New Bethel Baptist Church, drew up a list of names that he hoped would save Jasper. For 20 years, he has kept it tucked inside the Bible under the lid of his pulpit.

Recalling scripture where God offered to save a city for the sake of 10 honorable men, Lyons drew up his own list.

Among the names is a fellow minister, a woman who “played a big role during that time” and one of James Byrd Sr.’s good friends.

“I began to think of 10 people in Jasper who I knew were sincere and earnest,” he recalled. “And this is what I said: I said, ‘Lord, here are the 10 that I have found here in Jasper, Texas. You said if you could find 10 in Sodom and Gomorrah, you would save it. And here’s 10 from Jasper, Texas. Save it.’”

Faith, he and others say, may have done just that.

“There was kind of a rally in the faith,” said Eddie Hopkins, executive director of the Jasper Economic Development Corp., likening it to the coming together that followed the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. “I think that same kind of sentiment happened after James Byrd. I think there was a rally in the faith.”

The Ministerial Alliance, with leaders from about 30 churches in and around Jasper, stepped in immediately.

“We all spoke with one voice,” Lyons said. “When the Black Panthers came to town, the black preachers spoke out against it. When the Ku Klux Klan came, the white ministers spoke out against it. To show harmony, to show them that Jasper was of one accord.”

The work inside the community didn’t stop the stain from spreading.

“We were stereotyped,” said Billy Rowles, Jasper County sheriff at the time. “I was stereotyped as a pot-bellied, beer-drinking, East Texas redneck, racist sheriff. They portrayed me that way and our community as a bunch of racists and bigots and zeroes.

“It broke your heart, how they portrayed us.”

The economy suffered, too.

“Doctors wouldn’t come; businesses wouldn’t come,” said the Rev. Ron Foshage of St. Michael’s Catholic Church. “People moved out. It’s been very difficult because we live with this stigma.”

Foshage, Rowles and Lyons insist that the stereotypes were over-hyped. In 2019, there are signs that attitudes have softened.

A large tech support business headquartered in Brewton, Ala., is remodeling a building across from the courthouse for a new Texas location that promises to add as many as 250 jobs. Provalus chose Jasper out of 50 prospective cities across the country.

Landing the company wasn’t easy, said Hopkins of the economic development group.

“One of the things that came up in a conversation with the corporation’s president was James Byrd,” he said. “Not that we were going to have to convince him that we’d overcome it, but the clients that they work for. When they see ‘Provalus: Jasper, Texas,’ there’s always going to be those questions of, how safe will my employees be if they go to Jasper? Questions like that.”

People weren’t exactly fearful, said Century 21 Realtor Liz McClurg, but they were leery.

Prior to Byrd’s death, McClurg said, it took her an average of 30 to 45 days to sell a home. After, it would take about 270 days.

“Nobody wanted to come here — to live, to work, to start abusiness, to relocate,” she said. “I would just tell them: Come meet our people, come visit our shops, come see our schools. I stressed to my clients that the perception that they may have is not a pattern, it’s not a mentality.”

Foshage was part of a task force formed after Byrd’s death to tackle other issues.

“Myself and other members of the task force personally went to the banks, the courthouse, the car dealers. And we asked them to hire African-Americans,” the priest said. “And they agreed. Many people didn’t realize that there were no African-Americans in many of the Jasper businesses.”

Hopkins said the economy is getting better, but progress has been slow.

“It happened,” he said of the murder. “And we’re never, ever going to be able to dismiss the fact that it did. However, we have to live in spite of it. We have to go on. There has to be commerce. There has to be economy. There has to be life as normal as we can have it.”

Caden Bynum, 15, wasn’t alive at the time of the murder, and his mother, 29-year-old Linda Bynum, wasn’t old enough at the time to remember much. But both often are surprised by the opinions of those outside their town.

“We went to a college in Orange, and people looked at us like, ‘Oh my gosh, you live there?’” Linda Bynum said while dining with her son at a Jasper restaurant. “There are so many people outside of Jasper that look at this town as a racist town. Really and truthfully, it’s not. Most people are loving here.”

Caden Bynum, who plays on the high school football team, said the Byrd story occasionally is discussed in the classroom. He doesn’t hear other students making racist remarks. That’s not a word his generation would use to describe Jasper.

Capt. James Carter, a 30-year veteran of the Sheriff’s Office, blames the media for making the town appear that way.

“They blew it all out of proportion,” he said. “It wasn’t like they said it was.”

Carter grew up with the Byrds.

“We rode the bus together. We played after school. We went to church together. They were more like my family than a friend,” he said.

He went with then-Sheriff Rowles to inform the family of Byrd’s death. The details are as horrifying now as they were 21 years ago.

Byrd was a former vacuum cleaner salesman who lived on disability and had an apartment but no vehicle. So he walked, sometimes accepting rides from passing townsfolk.

He was walking home when King, Shawn Allen Berry and Lawrence Russell Brewer offered to give him a ride in Berry’s pickup. Out on an old logging road, court evidence would later show, they shared cigarettes and beer.

Then the unthinkable happened. Byrd was chained by his ankles to the bumper of Berry’s truck and dragged 3 miles down Huff Creek Road. His remains, naked and decapitated, were dumped outside a black church and a neighboring cemetery at the end of the road.

“I don’t think he was chosen,” Carter said. The attackers had “their minds made up.”

“It could have been anybody that night.”

Lyons’ congregation was in Sunday school when the news broke.

“It brought back memories of the ’30s and ’40s when our race was treated in that kind of way,” he said. “And I think most of us just couldn’t come to grasp, to believe it. We had come so far.”

The killers were all found guilty of capital murder. Berry, 44, is serving a life sentence, eligible for parole in 2038. Brewer was executed in 2011. King, the first to stand trial, is scheduled to die Wednesday evening in Huntsville.

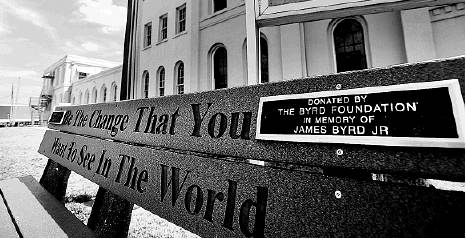

In 2001, then-Gov. Rick Perry signed the James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Act, creating harsher penalties for crimes committed on the basis of race, religion, age, gender, disability, national origin or sexual orientation.

Eight years later, Congress passed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, linking the Byrd case to the slaying three months later of a young gay man in Laramie, Wyo.

“Hate is a learned behavior,” Harris said last week as she prepared for the upcoming execution, which she and her sister Clara Taylor will attend. “Learned can be unlearned.”

Of the punishments, she said, “There’s closure in a sense that justice was served, but the reality of the impact that it created for our family is that James is gone forever. I don’t think anything could close that chapter.”

Those who lived through the tragedy haven’t forgotten, but they continue moving forward.

“Jasper, Texas, won,” former Sheriff Rowles said. “We may have a little scar and it’s healed up some, but we won.”

Robert Cowles, 62, a landscaper who moved to the area from North Carolina a few years after the murder, said he walks the same streets that Byrd once did with no fear, pushing his mower from one lawn job to the next.

As he walked past the now-shuttered Jasper Twin Cinema, he reflected on the parallels between his life and that of Byrd, a man he’d never met.

“He really was doing nothing but walking,” Cowles said. “He just loved to walk, like me.”

Foshage, the priest, remains a focal point for peace in Jasper. He spoke with Hearts Newspapers effortlessly, as if from a script, always smiling. It was clear he had done more than a few interviews over the past two decades.

Asked ifJasper is looking forward to the day the interviews will stop, Foshage kept smiling and answered softly:

“Yes, we are.”

Kim Brent and Andrea Whitney contributed. mbatson