Asylum-seekers sent to Mexico wait in tumult

Judge has blocked Trump policy, but their fates remain uncertain

By Lomi Kriel STAFF WRITER

CIUDAD JUÁREZ, Mexico — Juana Acosta was one of the unlucky ones, caught between whiplash changes to U.S. immigration policies this month.

Like tens of thousands of Central Americans, she brought her three young grandchildren from Honduras to the Texas border in March, hoping to be released to her daughter in Houston. Instead, Customs and Border Protection agents took away the children, whom she had raised alone since they were toddlers. They placed the 53-year-old in an overcrowded detention center in El Paso where, she said, she slept sitting up, stacked against other migrants, and wasn’t able to bathe for nine days.

Federal agents gave Acosta paperwork instructing her to appear at the Paso Del Norte International Bridge for her immigration court date in May and took her back to Juárez last week. The procedure made no sense to Acosta, who cannot read, but she was too focused on the fate of her grandchildren, whom she feared she would never see again.

“It was like the sky went dark,” she said recently from a migrant shelter on the outskirts of Juárez. “If I had known this would happen, I never would have brought them here.”

That’s the sentiment that Trump administration officials had hoped to elicit when they rolled out acontroversial policy known as the Migrant Protection Protocols earlier this year, forcing some prospective asylum-seekers to go back and wait in Mexico as their cases progressed through U.S. immigration courts. More than 103,400 migrants, mostly families from Central America, were encountered at the U.S. border and ports of entry in March, a record number that has overwhelmed all arms of federal border enforcement and those agencies in charge of migrants’ care.

Though overall apprehensions are still relatively low by historical standards, families now make up more than two-thirds of migrants coming to the U.S., and they are much more challenging to detain and quickly deport.

But late Monday, a California federal judge temporarily halted the policy, also known as “Remain in Mexico,” arguing in a 27-page ruling that it may violate federal provisions aimed at ensuring migrants are not returned to “unduly dangerous circumstances,” making it the latest of President Donald Trump’s hard-line immigration initiatives to be blocked in court.

The program had been slowly implemented — largely in secret — starting in January at the San Ysidro port of entry in California before being extended to Calexico, Calif., and to El Paso last month. In all, more than 1,000 migrants, mostly from Central America, have been returned to Mexico, including more than 200 to Juárez, according to Mexican government officials. Before Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen resigned unexpectedly on Sunday after traveling to the border with Trump, she had talked of ramping up the program to return hundreds of asylum-seekers a day to Mexico.

“This is a very significant blow to a policy they were counting on to allow them to keep people out of the country,” said Judy Rabinovitz, a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union who argued the case for halting the program. “They were looking at this as an unprecedented policy shift and wanted to apply it at a large scale to the border.”

In a written statement, White House officials lambasted the injunction for “forcing open borders policies onto an unwilling American populace.”

“This action gravely undermines the President’s ability to address the crisis at the border,” the White House said, adding that it planned to appeal the ruling.

Rabinovitz said the government would likely seek a stay of the injunction at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit in California and also at the Supreme Court. U.S. District Judge Richard Seeborg in San Francisco ruled that authorities can no longer return migrants to Mexico after 7 p.m. CST Friday.

Trump rages

In a late-night tweet on Monday, Trump also raged against the decision.

“A 9th Circuit Judge just ruled that Mexico is too dangerous for migrants,” he wrote. “So unfair to the U.S. OUT OF CONTROL!”

Meanwhile, hundreds of migrants such as Acosta waited in Juárez, Mexicali and Tijuana, uncertain of their fate. Rabinovitz said the ACLU was trying to determine how to handle them, but said that such migrants would “at a minimum” be allowed to remain in the U.S. after attending their first court hearing — given the injunction is not overturned.

“When they return for their next scheduled court hearing, they cannot be returned to Mexico,” she said.

In Juárez, overwhelmed state and local authorities breathed a sigh of relief. They had scrambled last week to find room to house the returned migrants, as the border city in Mexico is already sheltering more than 3,500 migrants from as far away as Brazil.

Acosta was sent at the last minute to a Methodist church in a dangerous neighborhood on the outskirts of Juárez where the pastor, Juan Fierro García, hastily made space in the overcrowded church for some 20 Central Americans returned by the U.S. government. A sign outside the shelter proclaimed “No Vacancy” in bold capital letters.

“We aren’t prepared, not for the influx of migrants, but even less so for those returned from the United States,” Fierro García said.

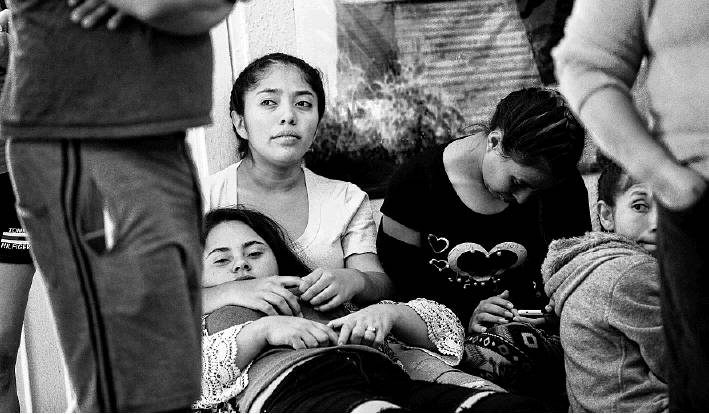

He said several migrants sent back under Trump’s short-lived policy had already left the shelter, some to try their luck again at crossing the nearby Rio Grande. A few had gone back to their home countries. But most stayed, clustering together in a pall of sadness that separated them from other migrants in the church, who had not yet tried to pass.

Many of the returned asylum-seekers said they thought their treatment by U.S. authorities had been unfair, and that officials seemed to pick at random which migrants would wait in Mexico and which would be freed to stay in the U.S. The U.S. government has not released more information on how it decided which migrants should be returned.

Sailin Murillo, a 23-year-old from Honduras, said U.S. authorities had already contacted her brother in North Carolina and arranged for him to buy her plane ticket when federal agents suddenly reversed course, sending her back to Juárez. She told them she didn’t want to sign the paperwork, but they responded that they would return her anyway, with or without her signature.

To pass the time in the shelter and attempt to spread some cheer, Murillo braided the hair of other “retornados,” who sat glum and mostly silent in a small circle in the back of the church. Murillo said she left Honduras to flee gang members who tried to rape her repeatedly; though she filed a formal complaint against them, police had done nothing to protect her. Others in the group were coming here from Guatemala and Honduras to reunite with family or seek work.

Many of the packets given to them by U.S. authorities lacked phone numbers for advocacy groups in El Paso, whom migrants could ask for legal representation. Others said that when they called those organizations, no one answered. Or when they did, some lawyers said they didn’t know how to represent them if they were already back in Mexico.

‘It’s very dangerous’

The general air was chaos.

Acosta sat in a darkened corner of the church, shutting her eyes. Tears streamed silently down her cheeks. She said she didn’t know what had happened to her grandchildren for more than 10 days. Finally, this past weekend, she was able to reach her daughter in Houston.

Her daughter said the U.S. government had called to say the children, ages 15, 12, and 7, were in a federal shelter for unaccompanied migrant children in New York and would likely soon be released to her care in Houston.

“It’s been horrible, horrible, really,” said the daughter, Lucy Medina, by phone from Houston. “I just don’t understand how they can send my mother back to a country that’s not even her own. It’s very dangerous. I’m worried. She’s depressed. She can’t sleep. She doesn’t have any money.”

Acosta said her mind was fixated on the last time she saw her grandchildren, before federal agents took them from her and she spent nine days in an overcrowded cell where she said all the migrants began to take on a putrid smell.

“Like a dead animal,” she said. “One felt embarrassed, truly.”

She said federal agents told her that she had committed a crime by bringing her grandchildren here and that she had come to believe them. She said she only sought a safer setting for them after gang members harassed her 15-year-old granddaughter, fearing they would try to force her into a violent relationship or something far worse.

But now she saw it differently.

“I asked God for forgiveness,” she said. “I should never have brought them here.” lomi.kriel@chron.com