THE SMART MONEY

Case for slavery reparations complex, but worth considering

Slavery reparations are having a moment.

Barack Obama, America’s first black president, never supported the idea, but the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates see things differently.

Former HUD Secretary and former San Antonio Mayor Julián Castro said that as president, he would set up a task force to look into reparations.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts is more forceful, saying we must “confront the dark history of slavery and government-sanctioned discrimination.”

California’s Sen. Kamala Harris answered questions about reparations by referencing her antipoverty proposals, although she did not explicitly link her initiatives to race qualifications.

Like Harris, Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey has also tried to thread the needle, with his campaign likening his anti-poverty program to a “kind of reparations” but without a race component to qualify.

The average U.S. voter doesn’t support slavery reparations. Polls show opposition to reparations still as high as 70 percent.

Nevertheless, like “Medicare for All,” this will come up as a talking point during the Democratic primary debates this year, as the party grapples with how far left it should go.

So, what is the case for reparations?

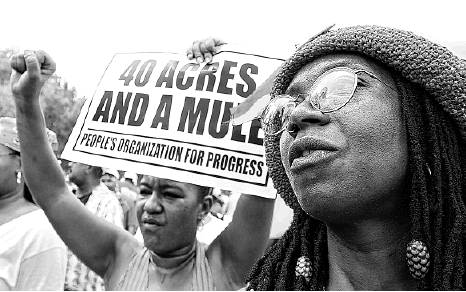

Union Gen. William Sherman set a precedent in January 1865 by carving 400,000 acres into 40-acre plots — from plantations captured at Sea Island, S.C. — for freed black men, and offering to rent mules to them to work the land. Sherman’s orders demonstrated a possible solution to the problem of compensating former slaves, setting expectations for post-Civil War reparations.

Even after President Andrew Johnson reversed Sherman’s orders following Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, “40 acres and a mule” became asymbolic request for the federal government to make good its unfulfilled promise to former slaves.

The federal government’s financial policies toward African Americans did not improve over the next 100 years, as explained in the excellent 2017 book “The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap” by Mehrsa Baradaran.

The federal government created the Freedman’s Bank in 1865 with Lincoln’s signature and congressional approval. At first, the bank encouraged thrift and banking until the (white) managers engaged in speculation and fraud that wiped out the bank, and with it about half the savings of all depositors.

W.E.B. Du Bois would later say of the banking scandal: “Not even ten additional years of slavery could have done so much to throttle the thrift of the freemen as the mismanagement and bankruptcy of the series of savings banks chartered by the Nation for their special aid.”

After 1934, when the Federal Housing Administration got into subsidizing mortgage loans to encourage wealth creation through homeownership, the federal government set up rules that forbade private banks from lending to what it deemed dangerous neighborhoods. The purpose of the rules was to enforce high loan quality for the safety of the banking system and government guarantees. The effect of the rules, however, was to create a red line around black and brown neighborhoods, with households unable to obtain financing from any bank participating in the mortgage subsidy program.

This “redlining” — which continued as official FHA policy for the next 3 ½decades but caused financial reverberations that continue to this day — ensured that traditionally black neighborhoods languished in a vicious cycle of high interest rates, undercapitalization, disrepair and a lack of asset appreciation.

White America has generally been blissfully ignorant of this history or the intergenerational effect that has on wealth inequality. The American dream that white America cherishes and proudly proclaims sounds quite different to black ears.

And then there’s a practical question: What would reparations look like?

Administering reparations could be a nightmare. Would people have to prove their slave ancestry to qualify for money? Do we have documentary and DNA records good enough to make accurate determinations? Is suffering under 20th-century Jim Crow enough, or is slavery the cutoff? Open-ended questions about reparations are easier to produce than practical answers.

“It’s about acknowledgment, that there was a wrong, a major wrong — and it’s about seeing how those actions reverberate to this day,” said Reniqua Allen, the author of “It Was All A Dream: A New Generation Confronts the Broken Promise to Black America.”

I sense money may not be the main thing white America needs to offer here.

Michael Taylor is a columnist for the San Antonio Express-News and author of “The Financial Rules For New College Graduates.” michael@michaelthesmart money.com | twitter.com/michael_taylor