HC INVESTIGATION

BROKEN TRUST

‘Highly Confidential’: Permanent School Fund’s investments have been shrouded in secrecy

Last of four parts By Susan Carroll, David Hunn and Matt Dempsey STAFF WRITERS

You might want to know how your inheritance — and that of your children and grandchildren — is being invested.

Who is handling the money? How much are they charging? What are the returns on your investment?

When it comes to your inheritance from our founding lawmakers, a $44 billion endowment created to forever help fund public education, the answers to those questions are obscured, buried in redacted reports and in documents labeled “Highly Confidential.”

The Texas Permanent School Fund, now 165 years old, is the largest education endowment in the United States. It is critical to public education funding in Texas, sending roughly $1 billion each year to schools to pay for textbooks and other costs at a time when many big districts are facing shortfalls in the millions.

But the fund is surrounded by a wall of secrecy built up by years of erosion of the Texas Public Information Act, the state’s 45-year-old open records law. Lawmakers have carved out dozens of exceptions to the law that have allowed government agencies to withhold and black out information that would have been presumed public in the past. A Texas Supreme Court decision in 2015 also made it easier for government agencies and corporations to argue that public disclosure of information could cause them competitive harm.

“It’s simply a recipe for corruption,” said Joe Larsen, a Houston lawyer who specializes in Texas public records cases.

The Houston Chronicle filed more than 100 public records requests as part of a yearlong investigation into the fund’s investments. When agencies seek to withhold records from the public, they are required to seek a ruling from the Attorney General’s Office, which decides whether the information should be disclosed. About two dozen of the Chronicle’s requests were forwarded to the Attorney General’s Office, which agreed with government agencies, ordering them to deny releasing or to black out portions of records nearly every time.

The result: The school fund’s agreements with private firms that invest billions of dollars and charge hundreds of millions in fees? Private. Records for multimillion-dollar real estate development partnerships? Confidential. Audits of those partnerships? Off-limits.

The Texas Public Information Act, enacted after a stock fraud scandal in the early 1970s implicated top state officials, reads in part: “It is the policy of this state that each person is entitled … to complete information about the affairs of government and the official acts of public officials and employees. The people, in delegating authority, do not give their public servants the right to decide what is good for the people to know and what is not good for them to know.”

Pro-business advocates say exemptions to the law are needed to help prevent corporations from potential harm from competitors.

“It’s important that proprietary information of businesses be protected when doing business with government,” said Chris Wallace, who testified last year as a business lobbyist opposing a bill aimed at increasing transparency.

Government agencies are seeking to withhold more and more records from the public. The Attorney General’s Office issued a record 30,939 public records rulings during fiscal year 2018. That’s up from about 5,000 in 2000.

Last session, Rep. Giovanni Capriglione, a suburban Fort Worth Republican, introduced a bill aimed at counteracting secrecy stemming from the 2015 Supreme Court decision, Boeing v. Paxton. That decision allows the government to keep secret its contracts with private entities and other records if disclosing them would give an advantage to a competitor.

The Texas attorney general has issued more than 2,000 rulings since then withholding access to information based on the Boeing decision. That ruling was cited in several responses to the Chronicle’s requests for information about the school fund.

“Thousands and thousands of legitimate requests have been denied using that broad ruling,” Capriglione said. “Our system of government is based on checks and balances, but the public can’t check what they can’t see.”

Capriglione’s bill ran up against corporate and government opposition last session and died in committee. He is trying again this session with a bill that would require the disclosure of contracting information not specifically exempted from disclosure.

A secretive fund

The Chronicle previously reported that the school fund has failed to match the growth of peer endowments while paying out hundreds of millions in fees during the past decade. It has sent less money to schools, adjusted for inflation, than it did decades ago, when the fund was much smaller.

Unlike the state’s other major investment funds, such as the Teacher Retirement System, the school fund only publicly reports gross returns on investments in annual reports, not factoring in how much it pays in fees to external fund managers.

The State Board of Education administers $34 billion of the endowment with staff of the Texas Education Agency. The Chronicle tried for nearly a year to get a full accounting of how much external fund managers charged for its investments.

Fund managers typically charge a 1 percent to 2 percent management fee and then take a cut of about 20 percent of the profits — so-called “carried interest” — once returns surpass a set hurdle. The investments run for years. Fees are paid continuously, but carried interest charges accumulate over time.

Unlike the land board and several other Texas public investment funds, the education board did not provide the amount of carried interest it had incurred, in response to public information requests.

“We do not maintain data on accrued or estimated carried interest,” the board staff said in response to a public records request. “Even if we maintained the estimated carried interest, we do not believe that is what the Act requires because it only requires compensation that has been ‘assessed’ and not that which is ‘estimated’ or ‘accrued.’ ”

Holland Timmins, the chief financial officer of the fund for the education board, said it did not start systematically tracking carried interest in its private equity and real estate returns until October 2017. Timmins also said he was unable to report how much the fund had paid in investment expenses, which are different from the fees and carried interest.

“Underlying expense data is not compiled or tabulated in a manner you would like to see,” he said.

Tom Maynard, a member of the education board, said Tuesday that the education board is not secretive.

“We've never had a secretive deliberation. I've only been in executive session one time, to discuss a lawsuit,” he said.

The School Land Board, which invests the state’s oil and gas royalties, controls about $10 billion of the endowment.

The land board insisted it could only provide a full accounting of its fees that includes carried interest on a calendar-year basis, making it impossible to compare with what is reported to the Legislature, which is on a fiscal year basis ending each Aug. 31. It also did not respond to repeated requests to clarify the difference between the fees and millions in expenses listed in its quarterly reports.

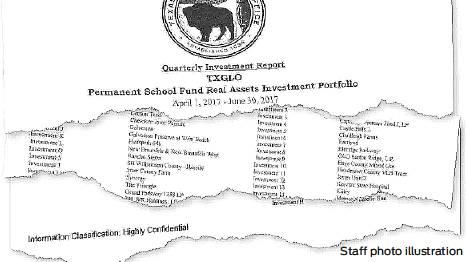

For years, it labeled its quarterly investment reports “Highly Confidential.” It key-coded real estate investment returns, and board members were given the key only behind closed doors.

That three-member board, led by Texas Land Commissioner George P. Bush, labeled 150 files involving public land deals made on the endowment’s behalf as “confidential” because they are part of ongoing development deals, including one that dates back to 1998.

The agency cited a 2007 amendment to the Natural Resources Code that makes information related to the development, location, purchase price or sale price of School Land Board property confidential until all deeds in a development are recorded and performance requirements satisfied.

“We are out in the market, actively trying to develop and sell these properties,” said Mark Havens, chief clerk of the General Land Office, which acts as the land board’s staff. “We are actually bidding against ourselves if someone can come in and go, ‘Oh, you know, they have this dollar amount in here, certainly they will take this amount.’ ”

While the Public Information Act offers the government an exemption for real estate deals — making records off-limits until a sale is complete — the Natural Resources Code is far broader, Larsen said.

“When is the final deed finally recorded in something like this? My goodness. ‘Never,’ is the short answer to that question.”

The 2007 amendment was authored by former Sen. Jeff Wentworth, who did not return phone calls, and sponsored by former Rep. Sylvester Turner, now Houston’s mayor. A spokesman for the mayor said Turner could not recall the bill.

Accidental disclosure

After staffers at the General Land Office accidentally released an unredacted, internal database of its land sales, showing it had sold thousands of acres ofland at steep losses to campaign donors to influential politicians, they asked the Chronicle to destroy it. The newspaper did not.

They also accidentally released two confidential files for a development in Sugar Land managed by a campaign donor.

“The GLO hereby demands you immediately return any and all confidential documents,” the office’s open government director wrote. The newspaper declined to do so. The GLO’s confidential records showed the agency had underreported millions in expenses for the Sugar Land development in its quarterly investment reports.

The land board also created 20 limited liability companies, all named Capitol Co-Investments, that combined have invested more than $664 million alongside primarily private equity firms. When the Chronicle requested to see the partnership agreements and audits for the co-investments, the land office cited several exemptions to the public records law, including one passed in 2005 that declared confidential “all information prepared or provided by a private investment fund and held by a governmental body” that is not listed in one of 16 specific provisions.

Those provisions include disclosure of how much is invested, how much is charged in fees, and what the return on investment has been. But anything not specifically mentioned — contracts, audits, agreements — is confidential under that law. The land office also cited the Boeing ruling in seeking to withhold the information. The attorney general agreed.

Rep. Terry Canales, a South Texas Democrat, said the public’s trust is shaken by the wide interpretation of the Boeing ruling and the lack of government transparency.

“Sunlight is the best disinfectant,” Canales said. “One of my favorite quotes is ‘When you turn on the light, the roaches run.’ ”

Larsen, the public records lawyer, said when he speaks publicly about the information act, “I feel like I’m giving an autopsy report.”

“People will say, ‘You’re exaggerating,’ ” he said. “I’m not exaggerating. You literally cannot get any information about what government bodies are paying for goods or services.”

“It is dead,” he said.

Staff writer Jeremy Blackman contributed to this report. susan.carroll@chron.com twitter.com/susancarroll

ONLINE

To catch up on the series, go to houstonchronicle.com/brokentrust

INSIDE What could be done to make the Permanent School Fund more accountable to the public?

The series

Sunday: Weak returns, dwindling payouts

Tuesday: Friends get benefits

Thursday: A big “haircut”

Sunday: “Highly Confidential”