Districts get say in how they’re rated

New Texas law allows locally created framework for judging achievement

By Jacob Carpenter STAFF WRITER

Since the creation of Texas’ public school accountability system 25 years ago, Lone Star educators consistently have lodged one chief complaint: It relies far too much on standardized test scores.

Education leaders often say the rating system reduces schools to results from the once-a-year assessment known as STAAR (State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness), providing an inaccurate and incomplete picture of school performance. The system, they argue, incentivizes “teaching to the test” at the expense of rich, innovative instructional practices that would benefit students more.

This year, that could change.

A new Texas law will allow school districts — if they get state approval — to create their own accountability systems for judging performance on their campuses, with those locally-developed scores counting for up to half of their state-issued ratings. Districts will be able to use numerous metrics unrelated to STAAR to evaluate school accomplishments, including student attendance, participation in fine arts and extracurricular activities, student health offerings and discipline rates.

School administrators and education advocates across Texas have heralded the change, declaring that local accountability frameworks will remedy some issues perpetuated by the state’s test-driven rating system. Several districts, including Alief and Humble ISDs in Greater Houston, are expected to submit local accountability plans for state approval this year. Ten more, including Spring ISD, have indicated interest in participating next year.

“There has been very little room for the community to be heard about what their schools should do because we follow a very strict system prescribed by the state,” Alief ISD Superintendent HD Chambers said. “At least now we have some say.”

In the age of data-driven accountability, Texas legislators and education leaders constantly debate how to properly measure the performance of districts and schools. The results are used to guide policy and hold decision-makers responsible for outcomes.

Historically, state leaders have rated schools based on various results tied to standardized tests. Under the current accountability framework, schools largely are scored on raw achievement, year-over-year growth and success in closing achievement gaps as determined by STAAR performance.

Results from STAAR account for 100 percent of elementary and middle school ratings. STAAR scores dictate 58 percent to 100 percent of high school ratings, depending on performance, with the remainder determined by graduation rates and measures of readiness for college or a career.

The results are converted into A-through-F letter grades for districts and campuses —with high stakes attached to the scores. A positive rating can attract more families to aneighborhood, drive up property values and highlight top employees in a district. Conversely, a negative rating can hurt confidence in a campus, drive away families and put additional pressure on school leaders to improve academic outcomes. In extreme cases, repeatedly low ratings can lead to dramatic state intervention, including forced campus closures and replacement of school boards.

“I think we would be naive to think parents don’t look at that and use it as a barometer” of a school,” Chambers said.

In response to persistent complaints about overreliance on STAAR scores, state legislators passed a law in 2017 allowing districts to craft their own accountability frameworks. To ensure fairness, state law dictates that the Texas Education Agency review and approve any local accountability systems. Districts also must use the current A-through-F rating scale when scoring their schools. In addition, they cannot apply local accountability scores to campuses rated “D” or “F” by the state, denying them the opportunity to raise low grades through metrics unrelated to test scores.

In interviews, several school leaders lauded the shift toward increasing local control over accountability, while pushing for even greater flexibility in the coming years.

“We’re really excited because we think that the state is starting to listen to what the communities are saying,” said Mary Kay Gianoutsos, director of evaluation in Humble ISD. “There are strengths at every campus that STAAR scores can’t measure.”

The local challenge

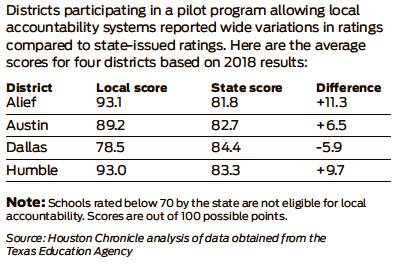

Ahead of the rollout of local accountability systems this year, 19 Texas school districts have spent several months participating in a pilot program, designing their own hypothetical frameworks. Twelve of those districts submitted formal plans and “what-if” grades based on data from 2018.

The results illustrate the possibilities for districts to employ unique measures to rate schools, while also exposing the complexities of allowing multiple methodologies.

Pilot districts used dramatically different tools for evaluating campuses, reflecting their locally-held educational values. In Alief ISD, administrators created a framework with 28 metrics, focusing heavily on availability of programs, participation in post-secondary courses and community engagement.

In Dallas ISD, the local accountability system largely relies on students’ year-over-year growth on various tests, as well as results from satisfaction surveys given to parents, teachers and students.

The multitude of possible metrics prompted some tug-and-pull.

Districts often wanted wide discretion to craft their frameworks, while state officials sometimes limited their plans in an effort to ensure reliability, rigor and validity. Some district leaders said they felt TEA leaders were too insistent on requiring “outcomes-based” metrics, such as results from assessments or participation in program offerings. Others wanted greater control over the weights assigned to certain criteria.

Seven districts, including Clear Creek and Spring Branch ISDs, bowed out of the pilot.

“I understand the state’s needs, and the federal regulations require a certain amount of reporting, but our hope as a district would be that the state is willing to embrace a variety of different measures,” said Spring Branch ISD Superintendent Scott Muri, whose district received a “B” grade in 2018. “It was really (about) the weighting for us, and that’s partly defined by the legislation and part by the state’s interpretation of the law.”

The wide variation in evaluation systems also produced dramatically different results across districts — a concern raised by some education advocates during the creation of local accountability legislation. Some districts also rated their schools significantly higher than the state, raising questions about the potential for accountability grade inflation.

In Alief and Humble ISDs, every school received an “A” or “B” rating under their local accountability frameworks, while slightly more than half of Dallas ISD schools received a rating of “C” or worse under its local system. About 90 percent of Alief and Humble ISD schools scored higher on their local system than the state system, compared to 9 percent in Dallas ISD.

In a statement, TEA officials said they are “still working with pilot districts to find the right approach to setting cut scores that reflect a shared rigorous expectation for students,” adding that it “isn’t necessarily a goal to ensure consistency between state and local components.”

‘Complex work’

Chambers, the Alief superintendent, said he would “hope that (our schools) would score better when looking at the whole child,” instead of measuring exclusively by STAAR scores. Dallas ISD Superintendent Michael Hinojosa shrugged off questions about fairness in light of the disparate pilot results.

“There’s a little bit of dissonance, but we think it’s a right way to handle it for us long-term,” Hinojosa said. “If we’re a little harder on ourselves, that’s OK. We expect a lot out of ourselves.”

District and state officials acknowledged that some aspects of local accountability systems will change ahead of the official rollout in August. TEA leaders plan to publish proposed local accountability rules by March, with an opportunity for public feedback before they are finalized in the summer. Pilot districts expect to tweak their preliminary systems in 2019.

For now, some supporters and opponents of high-stakes accountability are encouraged by Texas’ efforts to develop deeper methods of school evaluation.

Molly Weiner, director of policy for the conservative-leaning education reform advocacy group Texas Aspires, which has lauded the state’s current accountability system, said she hopes districts and the state strike a proper balance between flexibility and rigor.

“I think we’re cautiously optimistic that districts, if they’re really thoughtful about this, will be pulling in some interesting metrics,” Weiner said. “We really like innovation and people closest to schools making decisions. At the same time, we weren’t confident in the track record that districts have in being honest with themselves and their communities about the actual performance of their schools.”

Muri, who frequently has criticized the state’s test-based accountability framework, said he will continue advocating for more local-level authority. Although his district backed out of the pilot, Muri said, he sees value in local accountability systems — if done right.

“It’s incredibly complex work,” Muri said. “Do we have the answer in Spring Branch ISD? I think we have an answer that makes sense for us, that we’re pleased with. I think, as a state, we have to keep working on the possibilities. It’s worth the effort.” jacob.carpenter@chron.com twitter.com/chronjacob