MUSIC

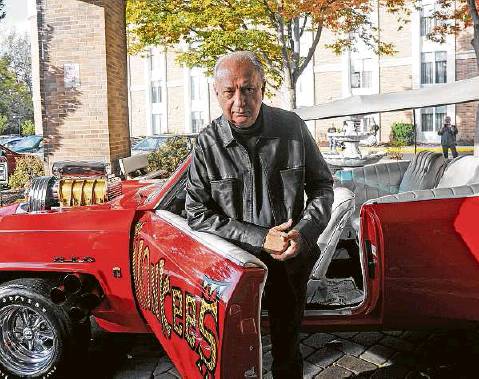

The subtle genius of Michael Nesmith is easy to embrace

By Andrew Dansby STAFF WRITER

“One person’s blues is another’s jazz.” Michael Nesmith wrote that in his 2017 autobiography, “Infinite Tuesday.”

Nesmith was, I believe, referring to the way a songwriter can have one intention, but once a song finds its way into the world, tens or thousands or millions of people will interpret the words in many varied ways.

He brings up “A Different Drum,” asong he wrote in 1965. Two years later, Linda Ronstadt recorded it with the Stone Poneys and scored ahuge hit. The song has been covered over and over since. It has become a standard of sorts.

Nesmith calls it “a lamentation,” and laughs.

“It’s this sad song, full of melancholy, about acouple that can’t seem to get together. Who are on a different page. He likes different things than she likes. And I have people come up to me and say, ‘That’s our song. They played it at our wedding.’ This is a song about two people breaking up. Of course, I never say that. But what do you do?”

What do you do? The phrase sounds like the title of a Nesmith album. Most long-spanning music careers follow a certain path: struggle, rise, peak, fall, comeback, death. Put those elements on a platter and shatter it, take the shards and glue them into a sculpture. That’s Nesmith’s career.

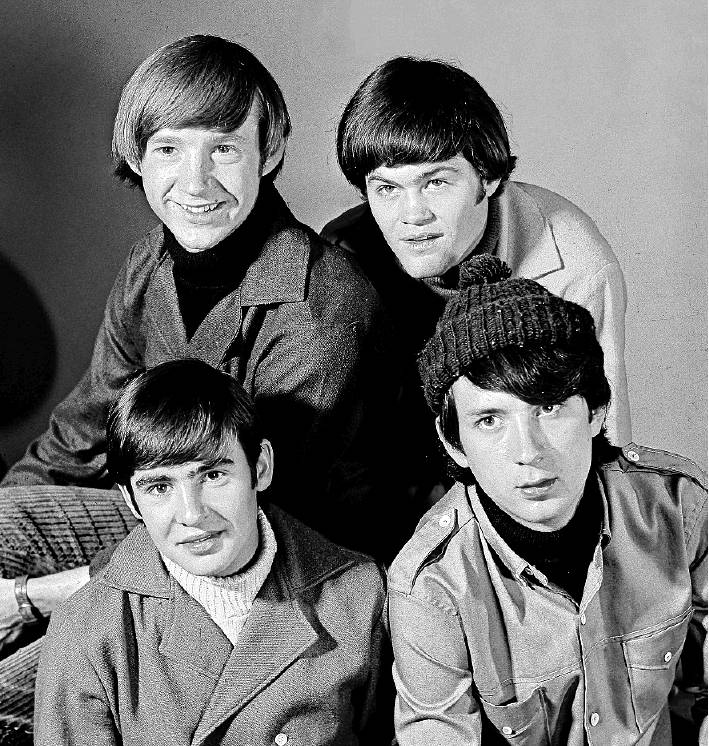

So this weekend he comes to Houston, the town where he was born but barely remembers, playing The Heights Theater with a 21st-century reboot of a band that broke up 40 years ago amid stifling public indifference. Sometimes that’s how things go. The shorthand with Nesmith will forever be the serious guy in the green sock hat with the Monkees, where he twisted ageless riffs out of his Gretsch guitar, and wrote some of the band’s best songs and helped steer the group to independence from the TV show and its producers who preferred puppets to players.

Nesmith assembled a remarkable band after the Monkees, the First National Band, which followed the branches of American music back to the 1920s, an era before radio untwisted the twine of country, blues, gospel and jazz into separate strands.

“He didn’t write like anybody else in the ’60s and ’70s, both with the Monkees and the First National Band,” says friend and admirer Billy Bob Thornton. “Just listen to ‘Joanne,’ you can hear it all in that song. He found this space that was entirely his own.”

Nesmith and the First National Band created arootsy sound far removed from Gram Parsons’ long-haired honky-tonk, which — along with a premature exit — secured Parsons’ legacy as a pioneer in the amorphous, not-quite-genre known as country rock.

Unlike Parsons, who died at age 26 in 1973, Nesmith had the good or ill fortune to stick around. Sometimes the long tail bears gifts, though.

Four-plus decades after he released three albums with the First National Band — pedal steel guitarist Red Rhodes, bassist John London and drummer John Ware — Nesmith has found the listenership for those records grew from coterie to cult.

“It was like asecret handshake,” he says. “I kept coming across people at meet-and-greets, at solo shows and Monkees shows, who loved those records from a band that just never got any traction. They seemed to understand what we were doing.”

Nesmith recalls a time years ago when he got his car serviced, and the mechanic glowed over his car’s “four-star Continental Tires.”

“He said, ‘That’s a mighty fine tire.’ I had no idea that was some secret society, but it’s sort of the same thing with these albums.”

The cult is different than those who surround the many scruffy insurgents who meddled with country music’s sometimes rigid sound in the 1970s. Nesmith points out Parsons “was a Harvard guy, with this literary thing going on. He could create a narrative, but we tried to avoid that dynamic in the First National Band. We were never going to do ‘Me and Bobby McGee,’ either. It just wasn’t the same thing.”

If Nesmith’s type of roots music had a decoder ring, it came at the end of “Magnetic South,” the First National Band’s masterpiece debut from 1970. The band covered the 1930s tune “Beyond the Blue Horizon,” a song that actor Jeanette MacDonald recorded for the film “Monte Carlo” that became a hit.

Nesmith in the ’70s sounded dialed more into vaudeville than Nashville, further evidenced by “Silver Moon” from the second First National Band album.

Of course, he’s a little elusive talking about it. He calls the vaudevillian observation “astute,” but then admits he lifted the arrangement for the song from Gary “U.S.” Bonds.

Still Nesmith refers to his repeated returns to an old Tin Pan Alley trick of putting sad lyrical content with plucky instrumentation.

“That is a terribly sad song about bitter disappointment,” he says, laughing.

He points out he was working in a different mine than more traditional country music, where songs about drinking were inspired by “life’s miseries or the vicissitudes of ajob you don’t like. For me these songs were more about a universal irritant. ‘I want this, and I can’t have it.’ People carry that with them all the time. It’s like anest of insects that don’t belong somewhere. Now, that is great fodder for a song.

“That doesn’t mean everybody will get it. So I just smile and say, ‘I’m glad you like the song. And though I haven’t met your wife, if she’s anything like ‘Joanne,’ you’re a lucky man.’ ”

One person’s blues is another’s jazz.

Nesmith released “Nevada Fighter” with the First National Band in 1971, then formed a new band (the Second National Band, naturally) and put out an album, followed by a duo recording with Rhodes titled “And the Hits Just Keep on Comin’,” suggesting Nesmith had asense of humor about it all.

He famously inherited a lot of money when his mother died in 1980. Bette Nesmith Graham grew up in San Antonio and gave birth to Nesmith in Houston in 1942. She divorced and moved a few years later to Dallas, where Nesmith was raised. Bette famously invented Liquid Paper, a company she sold for millions just a few months before her death.

Nesmith in the ’80s prominently moved into the video sphere, creating music videos, TV shows and producing films. Over the past 25 years or so, he always treated the individual Monkees as close friends, even when he held the band and its legacy at arm’s length.

If Nesmith seemed confounded by the curious course his career ran, he says it never bothered him too much.

“It’s just not my M.O.,” he says. “I let those things slide before I become too bemused.”

In 2016, he reunited with Peter Tork and Micky Dolenz for a Monkees show in Los Angeles. Nesmith had just made a record with the old gang, but as was often the case, he sat out the tour. At the Pantages theater in LA that night, Nesmith introduced the song “Tapioca Tundra” with a heartfelt story about writing it, following the first time the Monkees played a concert as a proper band in 1967. “We decided there was another presence up there with us,” he said. “Peter thought of it as ‘the Monkees’ and we all thought of it as you.”

Nesmith says the introduction, “maybe had to do with the passage of time, closing a chapter for me with the Monkees and so forth.”

What’s fascinating to me as a listener is how ageless that 50-year-old song is, when so much music from its era sounds stuck in time, like a faded tie-dye shirt. Like many of Nesmith’s songs, “Tapioca Tundra” is opaque thematically, with little lyrical references (ragtime and tattered shoes) that further underscore that affinity for songwriting during the 1920s and 1930s.

The song is melancholic and a bit wistful, qualities that have made Nesmith’s songs so durable over time. As a writer and as a singer, he never really felt the need to bust a gut, or emote to the point of play-acting.

“Melancholy is a subtle notion,” he says. Subtly.

Subtlety and understatement fit Nesmith well. He is, after all, the guy who wrote a song called “Grand Ennui” for the First National Band. He left misery to the “real” honky-tonk singers. Nesmith rearranged “Grand Ennui” for his current tour. He gave it a bit more drive, with an arrangement inspired by Texas singer-songwriter James McMurtry’s “Choctaw Bingo.”

On more than one occasion, Nesmith talks about his songs by comparing them to scenes in movies. “Grand Ennui” is one where “the driver looks out the back window of the car and finds the cloud is keeping pace.”

If a grayness comes across in Nesmith’s tone with metaphors, well, he’s 75, and his touring First National Band is all new, because half the members of the original group are dead. Then, in June he collapsed during what was initially described as a “minor health issue.” The experience already sounds a little like a Nesmith song when he describes it because it was more than minor, even with his eloquent understatement.

“I guess it was described as minor,” he says. “But anytime you get quadruple bypass open heart surgery there’s not a lot of conviviality in the looks on people’s faces. I tell you, to this day, I had no idea what the hell anybody was doing. They cut me apart, put the pieces all over the ground and then put them back in. It hurt like hell. And then I got out of it with no more pain involved.”

So it was alife-threatening moment that hurt, but then it didn’t. Others might describe the occasion in grand spiritual terms, or feel the need to provide metaphor for the pain.

But one person’s blues is another’s jazz. andrew.dansby@chron.com

Michael Nesmith and the First National Band

When: 8 p.m. Friday

Where: The Heights

Theater, 339 W. 19th

Details: $36; theheightstheater.com