Call me again; I dare you

Consumers are winning suits in telemarket fight

By L.M. Sixel

Almost any consumer can tell you that federal regulations restricting telemarketers from calling cellphones don’t have much effect. But now consumers are taking matters into their own hands, suing telemarketers in federal court and winning multimillion-dollar verdicts.

Federal telecommunication law allows consumers to sue telemarketers that violate the law, which prohibits sales or collection calls to cellphones without consumers’ written permission. Over a recent 17-month period, Texas consumers have filed 107 such lawsuits, the seventh-most in the nation, seeking penalties of as much as $1,500 for each annoying call that they’ve received. More than 3,100 similar cases have been brought across the country during that time period, an increase of nearly 50 percent from the previous 17 months, according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Consumers are winning, too. Pivotal Payments, a Texas payment processor, last year agreed to pay $9 million to settle a lawsuit that accused the company of failing to ensure the company it hired to make marketing calls to 1.9 million consumers complied with federal law.

Dish Network, the satellite television company, was ordered by a federal judge in North Carolina last year to pay $61.5 million to thousands of consumers on the national “Do Not Call” registry who received subscription pitches. And Wells Fargo reached a $14.8 million deal last year to settle a class-action lawsuit over automated calls to cellphones to sell car loans.

Jarrett Ellzey, a Houston lawyer, last year won a$9.8 million settlement in a class-action lawsuit against the Philadelphia insurer ACE American Insurance, which allegedly called thousands of consumers on the Do Not Call list to sell hazard coverage.

“They want the calls to stop,” said Ellzey. “It’s driving them crazy.”

Pace has accelerated

The Federal Trade Commission created the “Do Not Call” list 15 years ago to stop unwanted phone calls from telemarketers, updating the 1991 Telephone Consumer Protection Act that restricted unwanted commercial calls to both landlines and cellphones. The agency also put tighter restrictions on calls placed to cellphones, devised at a time when cellphone plans had limited calling times and added hefty charges if limits were exceeded.

Telemarketers were prohibited from using automatic dialing systems phones and computer-generated voices to call cellphones or leave pre-recorded messages without express written consent. And consumers could revoke their consent to receive calls on their cellphones, including calls from debt collectors.

But the pace of the robocalls has only accelerated, as technology made it cheap for banks, insurance companies, retailers and others to use automatic dialers and pre-recorded messages and hope that consumers press “1” for more information. You-Mail, an app that blocks robocalls, estimates that each American adult received an average of 100 robocalls to their cellphones and landlines last year.

The Federal Communications Commission receives more complaints about unwanted robocalls calls than any other category, logging 1.9 million during the first five months of 2017 alone. But it doesn’t have the money or manpower to go after all the violators, so Congress gave consumers the right to bring their own lawsuits against companies that call without permission and ignore pleas to stop calling.

Nearly 1,850 calls

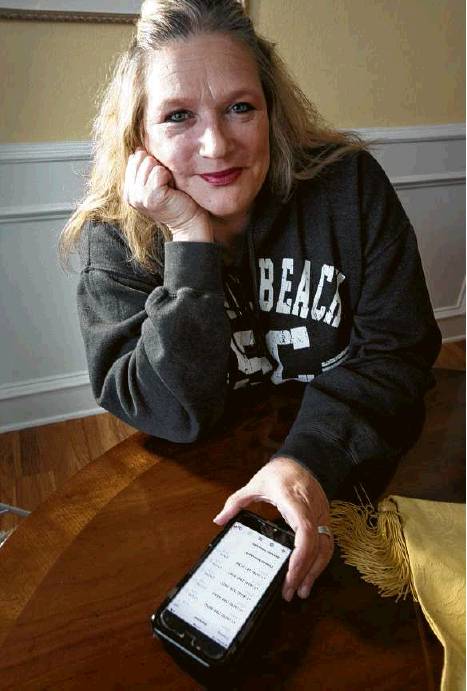

Tonya Stevens, 48, decided to exercise that right after she received nearly 1,850 calls from The Woodlands-based Conn’s to her cellphone over a13-month period. She bought a washer, dryer and other merchandise on credit for about $5,000 in 2014, but within a few weeks, collections calls began coming to her cellphone, as many as 11 times a day, even though Stevens said she was paying her bill regularly.

Stevens, who lives in Bonham near the Oklahoma border, agreed to be contacted by Conn’s through her cellphone when she made her purchase. But she withdrew that consent —a key factor in cases like this — by telling company representatives to stop calling and writing the same message on the memo line of her checks. Nothing worked, she said, until she hired a lawyer and filed a complaint with the Texas attorney general’s office.

“I was just fed up,” she said.

Michael A. Harvey, a lawyer for Conn’s, disputed allegations that the retailer violated the federal telecommunications law, but because of the litigation would not provide details of Stevens’ account. He added that Conn’s strives to create a positive experience for its customers, from the sales floor to when they pay off their accounts.

Daniel Ciment, the Houston lawyer who is representing Stevens, is planning to ask an arbitrator for $2.8 million in damages, $1,500 — the maximum damage award — for each of the calls to Stevens’ cellphone. It’s not unrealistic, he said, pointing to an arbitrator’s decision earlier this year that Conn’s must pay a Tennessee consumer $311,000 for 424 calls the retailer made in a four-month period after the consumer told Conn’s to quit calling his cellphone.

“It adds up quick,” said Ciment.

Ciment is a small player in a cottage industry of lawyers that file these consumer protection claims, which can generate significant fees, particularly in class-action suits involving hundreds or thousands of consumers. Unlike many other types of civil cases, the lawyers don’t have to prove damages for their clients to collect; they only need to show that telemarketers made unlawful calls.

But it’s not as easy as it sounds. While technology has made it easy for telemarketers to make the robocalls, technology also has made it harder to trace the calls. Software, for example, can make calls appear to be coming from across town when they’re being place across the country — or on the other side of the world. In addition, telemarketers have moved operations offshore, which puts them out of reach of U.S. law.

‘Professional plaintiffs’

’The U.S. Chamber of Commerce says these and other factors have led lawyers to target legitimate U.S. businesses rather than the “unscrupulous scam telemarketers” that the consumer protection law was meant to police. The lawsuits, which afew years ago were concentrated in just a handful of jurisdictions, have been filed in at least 42 states, according to the chamber, and given rise to a class of “professional plaintiffs” who are recruited by law firms and make a living by receiving phone calls and filing claims.

About four dozen law firms around the county file more than half of the total cases, the chamber said in a 2017 report, amounting to a group of serial filers that business groups describe as “entrepreneurial” law firms.

“It’s a profitable litigation model,” said Austin lawyer Manny Newburger, who represents financial institutions, debt buyers, law firms, and collection agencies. lynn.sixel@chron.com twitter.com/lmsixel